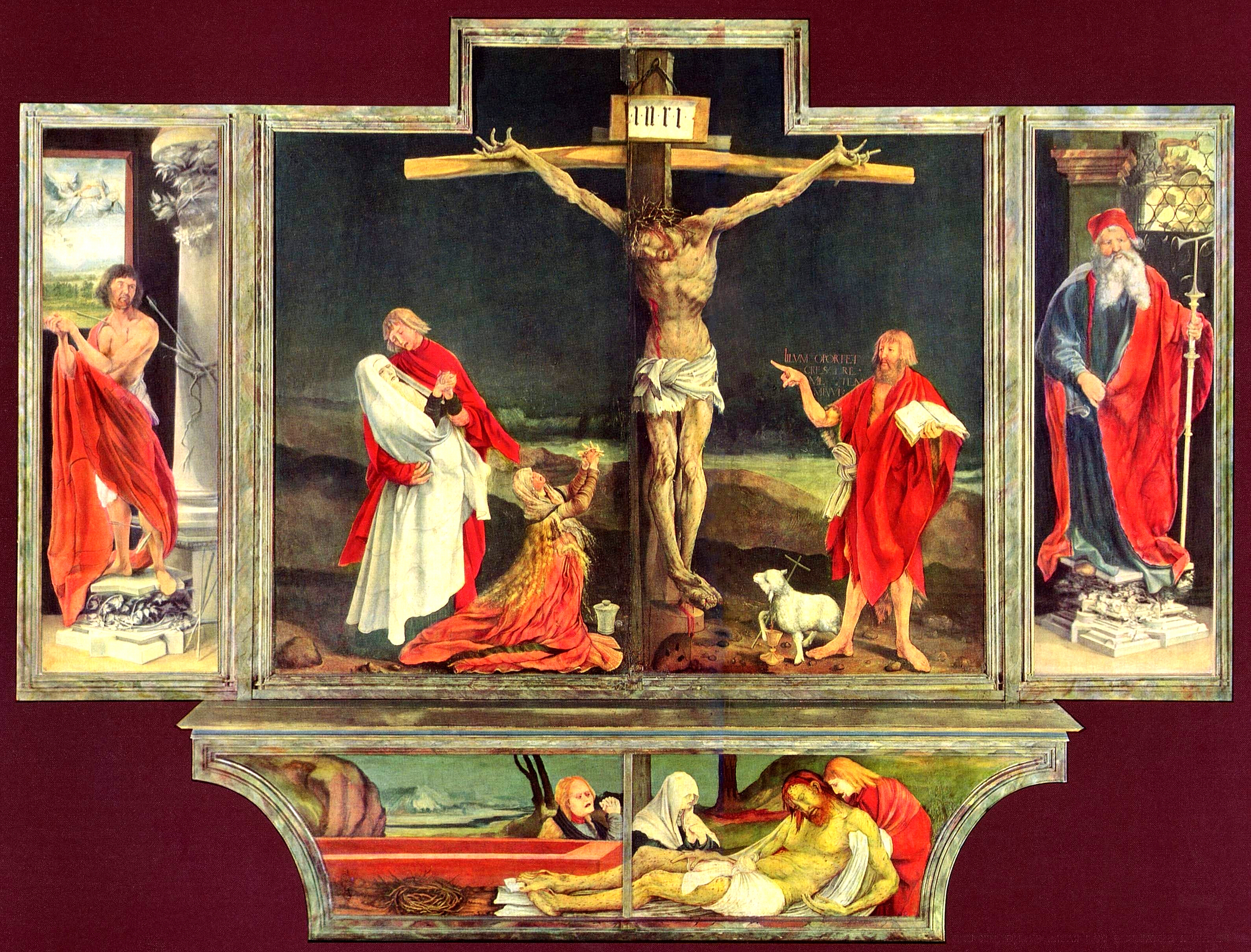

Grünewald, Saint Sebastian, The Crucifixion, Saint Anthony, Lamentation over the Body of Christ. Mixed media (oil and tempera) on limewood panels. At display at The Museum of Unterlinden, Germany. Photography: The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.

St. John the Evangelist, wearing contemporary (Renaissance) clothing, comforts Christ’s mother at the foot of the cross.

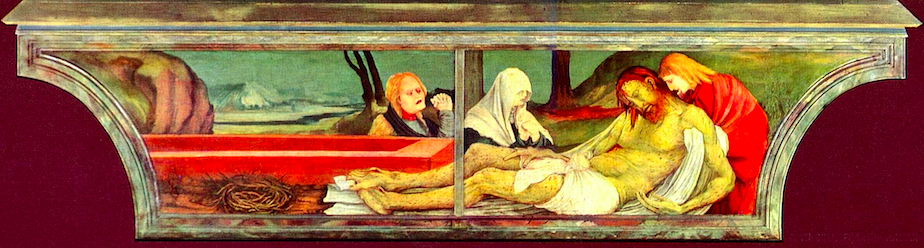

The majestic masterpiece on display at the Museum in Unterlinden in Germany is an example of a work painted during the German Renaissance. Like van Cleve’s painting, this altarpiece also depicts the crucifixion of Christ, but in the German version, the Baptist and the Evangelist have switched places, and the Baptist is now on the right hand of the viewer, and the Evangelist is on the left, embracing a mourning Virgin Mary. The Isenheim altarpiece also has certain non religious elements, most notably the antique pillars and the modern clothing of St John the Evangelist. The accompanying saints in this altarpiece are St. Sebastian and St. Anthony, placed on the wings in their ability to heal the sick, according to the Museum of Unterlinden webpage. Compared to van Cleve’s piece, there is less focus on landscape; however, the predello still conveys the growing importance of landscape in Northern Renaissance painting by depicting a mountain. There is also less focus on secular items, but the Isenheim altarpiece does allude to the Antiquity by depicting Greek pillars in the wings.

As in the van Cleve altarpiece, the clothing of the two St Johns helps emphasize their roles and similarities, and this is similar as in van Cleve’s piece. Again, as in van Cleve’s piece, the presence of the Baptist is anachronistic and he is portrayed as a prophet, placed in a scene where he could not possibly have been. However, in the Isenheim altarpiece, there are several differences in the Baptist’s presence, as well as symbolic differences.

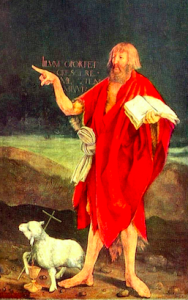

The Baptist is now pointing directly at Christ, and not the Lamb of God. This means that he is pointing directly at the sacrifice of God, not the symbol of it, as he did in van Cleve’s piece when pointing at the lamb. The lamb has human like characteristics and is holding the staff, which is usually associated with the Baptist. Furthermore, the contrapposto shows the istoria of how the lamb protects the Holy Grail, which ties together the body (the lamb) and the blood of Christ. This might symbolize how the way to salvation is through Christ’s suffering, and in this regard it gives the Baptist an eschatological aspect. It also looks forward to the judgment of man…

Furthermore, the Baptist is now the one who holds the book, not the Evangelist, as in the van Cleve piece. He is also accompanied by a slightly red writing on the black background, which according to the Museum of Unterlinden, states “He must increase, but I must decrease,” which is said to be an announcement of the New Testament and symbolizes the Baptist as the last prophet before Christ. Also, it harkens back to the Baptist’s role as a preparer of Christ. The Baptist’s role as a prophet is also enhanced by how he points towards Christ, predicting the sacrifice and salvation of Christ. This creates a certain lineage from the announcement of Christ, to the crucifixion, in terms of the Baptist.

Behind the Evangelist is the carrying of Jesus into his tomb, connecting the Evangelist to the sacrifice and resurrection of Christ. This is eschatological, as it points to the resurrection, and the salvation through Christ. Both the scenes are examples of continuous narrative. Together they tell the full story of Christ and include his figure in several different points in time: first his baptism, then his sacrifice, and finally his death [and resurrection—alluded to by the placing of the body in the tomb]. Van Cleve depicts several other scenes taken from the Bible, as well. Behind the baptism is what appears to be Christ preaching on Mount Sinai, where he proclaimed the end of the world (an eschatological element). This scene is interesting, as it is put into a Dutch landscape, which means that the Italian patrons wanted Christ in a Dutch context. This might allude to the weakened role of the Catholic Church following the reformation.

The scene behind St. John the Baptist’s head (in the van Cleve altarpiece) portrays Christ’s Baptism as well as Christ’s sermon on the mount.

A final aspect that represents a major difference in the two works is the use of landscape. Van Cleve has a distinct Dutch style in this regard, and there is amazing depth [and detail] to his landscape. He also fills the background with several secular and anachronistic elements. The buildings are modern, and the viewer can spot modern ships on the river in the background, alluding to the growing importance of commerce in Dutch society. More importantly, van Cleve uses the landscape to emphasize the roles of the two Johns, and the scenes introduce continuous narrative to the altarpiece. The scenes taking place behind the Baptist in van Cleve’s altarpiece shows the baptism of Christ in the Jordan River. This may symbolize a Eucharistic element as it alludes to the incarnation, and the scene places the Baptist in the narrative of salvation. Also, this is a scene from the life of Christ, which temporal occurred before the crucifixion.

The scene behind St. John the Evangelist’s head (in the van Cleve altarpiece) portrays Christ’s burial as well as Judas’ suicide.

Next to the cave behind the Evangelist is the scene of Judas hanging himself, alluding to the judgment of sinners and non-believers. This also show how the the narrative is structured from left to right, as the different events are chronologically order in that order.

It is interesting that the differences in the two paintings are so substantial, given that they were painted around the same time. This might have to do with the role of the patrons. According to the webpage of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the fact that van Cleve uses Italian saints on the right wing indicates that the painting was an Italian commission. The patron is also included in the altarpiece as a devoted Christian at the foot of the cross. The Isenheim altarpiece, on the other hand, includes saints that have a direct link to Christ and/or the crucifixion scene; St. Sebastian and St. Anthony both symbolize healing, and there is no patron depicted. Also, the setting of the saints is not incorporated into the scene, like in the van Cleve altarpiece, but is separated into rooms with antique elements. This means that the Isenheim altarpiece is harkening back to the antique, a general Renaissance trait, but is not really connecting the scene to the contemporary world like van Cleve.