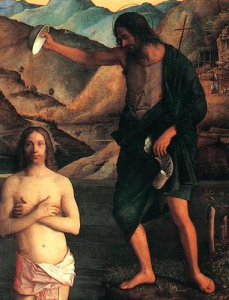

1500-1502. Giovanni Bellini (High Renaissance). Oil on canvas. At display at Santa Corona, Vicenza, Italy.

The Baptism of Christ depicts the Jesus’s baptism, when John the Baptist poured water over Christ’s head to metaphorically wash away sin. However, the scene in the painting does not take place in a river, as the story goes in the Bible. On the left-hand side there are three men dressed in contemporary clothing that have not been identified as saints or patrons (Allen). Their contemporary clothing, however, makes the three characters anachronistic. Above the scene is a dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, and at the top of the painting is God accompanied by angels. As opposed to the other altarpieces, the Bellini’s altarpiece of St John the Baptist does not have wings or a predella attached. These might be lost, or it might be that it is not an altarpiece, even though it is often referred to as one.

The similarities between the Bellini altarpiece and the van Cleve altarpiece show the extent to which van Cleve was influenced by Italian Renaissance. The perspective [shown in the landscape background] is vast and deep, as in the van Cleve and unlike the Isenheim piece. There are also anachronistic elements, like the buildings in the background and the contemporary clothing of the three saints on the left side, as mentioned. The landscape, however, is not as vast as van Cleve’s and does not contain the same ambiguity when it comes to secularism and religion, which may be explained by contemporary changes in society, as the reformation was changing northern Europe more than the traditionally Catholic Italy. Furthermore, Bellini’s altarpiece is distinctively Italian in its symmetric nature. God is centered directly above Christ, and you could draw a straight line from God, through the Holy Spirit and the Baptist’s bowl and down to Christ. The mountains in the landscape on both sides are somewhat symmetrical around the scene, drawing the attention inwards. This is very different from the Dutch altarpiece, where the landscape is vast in its nature, with much less symmetry but more focus on details. The same goes for the Isenheim altarpiece, where the landscape does not create depth in the same way, and an Italian artist would probably make the landscape in the predella much more symmetrical than Grunewald.

Also, the Dutch were emerging as a leading country in commerce. It is therefore interesting that the least secular painting is the Isenheim one because it was painted in the home of reformation – Germany. However, it is worth noting that the altarpiece was actually painted for a monastery, rather than a regular patron, which may explain this fact.

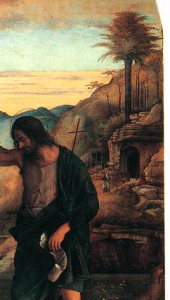

A lone hermit stands behind the figure of St. John, alluding to the Baptist’s nomadic lifestyle and Christ’s frequent wanderings through the desert.

This painting only features John the Baptist, but it still shows the history of salvation. The Baptist, in this case, is not anachronistic. The cave behind the Baptist symbolizes the darkness of sin and the death of Christ, but in Bellini’s painting the cave is connecting the Baptist, not the Evangelist, to the death of Christ. Still, this is eschatological, tying the baptism to the sacrifice and death of Christ, showing the span of salvation. This might emphasize the Baptist’s role as a prophet, but the lonely man outside the cave might also be a reference to the Baptist as a hermit, living alone in the desert. If it were the Baptist, this would be the painting’s only example of continuous narrative. Jesus also spent time as a hermit, praying in the desert alone, and this might allude to the importance of prayer and solitude as well as the resistance of sin (the temptation of the devil in the desert), all signs that connect the painting to the final judgment, and an important aspect in hagiography.