Aimee Stephens worked at a funeral home in Detroit for nearly six years when she wrote a letter telling her boss that she was transgender. Two weeks after, the Christian owned and operated funeral home terminated her job: not on the basis of job performance, but explicitly because she is transgender.

Aimee Stephens worked at a funeral home in Detroit for nearly six years when she wrote a letter telling her boss that she was transgender. Two weeks after, the Christian owned and operated funeral home terminated her job: not on the basis of job performance, but explicitly because she is transgender.

Aimee took her case to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which sued the funeral home for firing Aimee on the grounds of sex discrimination. Five years later, in March 2018, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit issued a resounding victory for Aimee, stating that discriminating against transgender people is a form of sex discrimination that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.”

The lawyers representing the funeral home from the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) accused the court of expanding the definition of “sex” and argued for the word’s strict protectionism. They petitioned that the Supreme Court take up the case to determine if transgender individuals are protected under Title VII, which could have broader implications for the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals across the country.

“They make the concept of gender identity itself seem frivolous by denoting it as immutable. The petitioners make slippery slope arguments about bathrooms to stoke fear about transgender people in public space,” explained Chinyere Ezie, staff attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights. “Sex is socially constructed… when you consider gender and intersex identities, you are working with terrain that makes something scientific that actually eludes scientific description.”

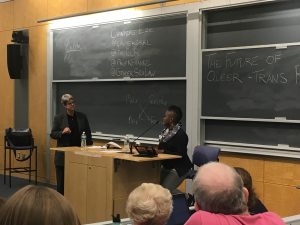

Last Monday, Chinyere came to Columbia Law School to discuss the future of queer and trans rights with Katherine Franke, director of the Center for Gender and Sexuality Law and Sulzbacher Professor of Law. Chinyere has spent years advocating for racial and gender justice and LGBTQI rights. Previously, she was a Staff Attorney at the Southern Poverty Law Center, and served as Trial Attorney at the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commissions.

As a trans rights practitioner, Chinyere has won several crucial cases in the fight for trans and gender rights. Yet, state and non-state actors are working hard to rescind this progress.

Current federal civil rights laws prohibit sex discrimination by employers, schools, landlords, and health care providers, through Titles VII and IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as well as Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. However, a provision in Title IX, which allows for religious-based exemption, is often deployed in the service of justifying unequal treatment of LGBTI individuals.

This is the provision that lawyers from the ADF sought to utilize to justify firing Aimee Stephens. Their demand that the Supreme Court should determine whether gender identity should be included as “sex” has led to the Trump administration taking steps to re-establish the definition of sex under Title IX.

The current administration has begun dismantling the fruits of victories in the hard-fought battle for trans rights. In 2016, the Obama administration issued federal guidelines requiring that public schools allow transgender students to have access to bathrooms, classes, and locker rooms that match their gender identity. Yet last February, the Education Department confirmed that it is no longer investigating civil rights complaints from transgender students barred from using bathrooms that match their gender identity.

In 2015, Chinyere represented Ashley Diamond, a trans woman whose offense was burglary and was sent to a series of high-security prisons for violent male prisoners. She was sexually assaulted on a regular basis and was denied her hormone medication after making pleas to access it, which she, then in her mid-thirties, had been taking since adolescence. She was regularly harassed by prison guards and, after asking for hormone therapy, was held in solitary confinement. The process of deliberate defeminisation led to humiliation, emotional and physical trauma, and suicide attempts.

Chinyere calls what Ms. Diamond was subjected to the “discrimination to incarceration pipeline,” that targets transgender individuals and people of color. Societal exclusion of trans people results in increased vulnerability on the school to prison pipeline. These risk factors push already ostracized individuals to the margins of society, which might demand involvement in clandestine channels of income as a means to survival. This, in addition to preconceived prejudices in the judicial system, results in their disproportionate incarceration.

“We wrote up a 50-page complaint that outlines all the issues that this population faces behind bars. It led to her being released from prison 8 years early, to Georgia removing what had been a long-standing policy of denying gender related healthcare to prisoners who didn’t have a prescription, basically in their pocket when they come into prison, and it made gender-related healthcare available to a whole universe of prisoners.”

The political climate around gender and sexual equality is riddled with uncertainty, with previous protections being rolled back. As Professor Franke pointed out, trans people’s interests have historically been excluded from the gay rights movement, which invested in the marriage campaign as the centerpiece of its publicity work. A struggle with the trans rights movement, she suggested, has been the lack of public education and support from civil society: “The federal government showed up too early and too aggressively when the cultural work hadn’t been done yet.”

Just a few weeks ago, the Department of Justice filed a brief in the case of Aimee Stephens arguing the Title VII does not prohibit discrimination against transgender workers. While the DOJ did not ask that the Supreme Court hear the case, it sides with the funeral home on the definition of “sex.” “The allyship of the government is going to wax and wane, and that’s happening very dramatically right now,” explained Chinyere. “Trickle-down rights are not viable.”

Justifiably, advocates and trans people are scared that the judicial progress will soon retrogress. Federal advocacy will undoubtedly become more challenging, but that does not mean that social change will be on pause. Trial courts, district courts, and individual states will increasingly be the battleground sites for fighting for human rights. What matters, Chinyere argues, is showing up for trans people where there’s need, rather than racing to expand the law. The assumption of criminality, devaluation of trans lives, and iniquitous access to public services demand the wider public to unlearn the heterosexism that is unjustly ingrained in our social fabric.

By Laura Charney