by Ulia Popova, a Visiting Scholar at Columbia University ISHR

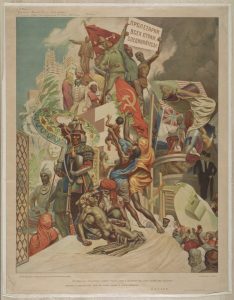

November 7 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, an event that set in motion one of the controversial political experiments of the 20th century, the development of a socialist state. The legacy of the Soviet experiment is contradictory, given the greatness of the idea that inspired it and the tragedies it engendered. The Soviet treatment of the rights of ethnic minorities is particularly instructive in this regard, not least due to its relevance to the contemporary debate over inclusion and diversity.

Terry Martin, a Harvard historian, called the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) the “world’s first Affirmative Action Empire.” With the exception of India, no other multi-cultural state before or after the USSR, Martin writes, took action of equivalent scope in support of the cultural and political rights of ethnic minorities. The architects of the Soviet Union envisioned it as a state based on the principle of self-determination of all nations. The new state was diverse: the first census in 1926 accounted for close to 200 distinct cultural communities composing the USSR. Lenin theorized self-determination primarily as political autonomy: the arrangement of the new state would offer oppressed peoples a unique chance to liberate themselves by taking control over their political destinies.

Soviet measures in the area of minority rights became known as “nationalities policies,” after the Russian legal term natsional’nost’ that captures a cultural identity of a group and a citizen, while also having a political component. Nationality linked a specific group to an explicitly defined territory, which that group was entitled to administer as its officially recognized historical homeland.

An elaborate and hierarchical system of institutions of self-government was developed to implement this vision on all levels, beginning with the Union republics, and going down to reach distant and demographically small cultural groups living in the Russian North. Measures of quota-based representation of minorities in the regional and federal institutions of administration reinforced the vision, helping ethnic leaders to advance to positions of power.

These policies were implemented in varying degrees throughout the history of the Soviet Union. Despite their promise of political liberation, the Soviet Affirmative Action did not afford minorities self governance. On the contrary, from the start these policies became instruments to maintain a centralized authoritarian state.

Why? The Soviet state architects were not concerned with protecting the institutions of governance that traditionally functioned within the ethnic communities integrated into a new state, such as, for example, kinship-based rule, prevalent among Soviet Asian communities, or the prominence of spiritual leaders (shamans) in decision making among remote indigenous Northern communities. Further, facing the threat of nationalism at the formation of the Union, Soviet leaders could not allow minorities to make decisions in accord with their local contexts and traditions. On the surface, Soviet policies guaranteed ethnic leaders an opportunity to institute a degree of control over their designated homelands, but in reality, the available means of governance were those devised to support communist rule. This approach stripped local authorities of their powers; their influence was limited to the private sphere as a group of new leaders, notoriously known as “ethnic party cadres,” replaced them. Trained in the Soviet system of education and employed within the state administration, they could only stay in power by serving their state and thus extending the institutions of authoritarian rule. The forms of local self-government they helped to institute were– to borrow from Stalin– “national” (i.e. ethnic) in form, “socialist in content.”

The legacies of the nationality policies are sadly known. During the Soviet times, they caused demographic catastrophe for a number of communities, most prominently to the Russian Northern indigenous groups, especially when implemented through forced relocations and industrialization projects. The structural and political arrangements these policies helped to produce became supportive of authoritarian rule during the post-Soviet times. In Russia, for example, a rise of ethnic self-determination movements during the 1990s engendered an extreme rise of autocratic governance leading to a contemporary approach to minority rights– to quote one observer– framed by Moscow’s attempt to “drive ethnicity out of politics.”

The wider significance of the Soviet Affirmative Action experiment is in its relevance to the contemporary projects of multiculturalism. Current visions of political equality often target measures that ensure inclusion of different groups into the state institutions in response to the history of their discrimination based on race, gender, culture and socio-economic conditions. While these measures provide opportunities to some minority individuals, they also support maintenance of the existing social and political order, as opposed to the reform that is promised rhetorically. As with the Soviet Affirmative Action initiatives, they strengthen the existing institutions of governance at the cost of widening the gap between those at the periphery of the system and those with power.

now finds itself in precisely the same position it was in 76 years ago. Perhaps the outcome will be different. Perhaps history is not in fact doomed to repeat itself. Perhaps, as the world dared to hope with Germany, the annexation of Crimea would be enough to appeas

quite a year

_________________

Kiedy polskie ekasyno, kasyna w koszalinie

History always repeats itself!