Samir Ahmad, is a PhD Research Student at the UNESCO Madanjeet Singh Institute of Kashmir Studies,University of Kashmir, Srinagar. He also serves as a contract lecturer at the same department. A former Fulbright Scholar, Samir’s research interests include India- Pakistan relations and the politics of Kashmir. He has recently published a book entitled, “The Kashmir Issue and its Resolutions: Relevance of Musharraf’s Proposal”.

Author Archives: Anushri Alva

Impact of Militarization on Education in Kashmir

By Samir Ahmad

While it is relatively easy to define militarization, measuring the extent and degree of militarization in a particular society can be a daunting task. Militarization also does not lend itself to a single unique measure: e.g. the amount of expenditure on the deployment of military resources in a particular state, region or country. In addition to budget allocations and expenditure, many other indicators of militarization demand rigorous conceptual constructs.[i]

Over the last two decades the number of the military personnel on active deployment is consistently increasing in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In the early 1990’s the Indian state deployed five divisions, i.e., around 250,000 soldiers, including 1,500 companies of paramilitary forces and state police, in the Kashmir valley alone[ii] which according to different reliable sources has reached up to more than half a million now. This is despite the fact that the number of militants has considerably declined over the last ten to fifteen years. As per the recent public declaration by the DGP of Jammu and Kashmir, there are less than two hundred militants active in the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir.[iii] In other words, there are 81 soldiers for every square mile and roughly one soldier for every ten civilians against the national average of about 800 civilians per soldier. Ninety five percent (95%) of these military men are non-Muslims (Muslims form the majority of the state population) and non-Kashmiris, and therefore, hardly bear any sympathy for the local population.[iv] A European Union delegation during their visit to the State in 2004-05 declared Jammu and Kashmir a beautiful prison on earth. Moreover, the military institutions have been equipped with enormous arbitrary powers under various draconian laws such as, Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), Jammu and Kashmir Disturbed Areas Act, Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA) etc. All these laws confer complete impunity to the Indian military in the State of Jammu and Kashmir that has led to a complete emasculation of the democratic machinery, if any, in the State.[v]

Given this situation a need was felt to measure the extent of the impact of militarization on the education system and the school children in the Kashmir valley in the last twenty years of conflict. The broader objectives of one such study, that I conducted, were; assessing the various kinds of impacts of the military camps/bunkers established within and in the vicinity of schools and other educational institutions, exploring and measuring the relation between the presence of security personnel within or around schools and the sense of insecurity among school going children, and exploring the link between the presence of the military and the growth of the various psycho-social problems among the student community in the Kashmir valley. The purpose of the study was also to investigate, whether the presence of the military was causing any impediment for students to have free and safe access to their schools. This study is of particular importance because it provides information to sensitize various concerned government bodies/institutions, media, civil society groups (within and outside Jammu and Kashmir) and other stake holders, including the general public, about the repercussions of the widespread deployment of the military and paramilitary forces especially within the civilian areas in the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

During the research 360 students (including pilot sampling) were interviewed, and each student was asked to answer questions related to the issue of militarization and its consequences on the education system. During the study, students shared their experiences of various violent incidents and the difficult situations they encounter every day. In the various phases of the study, it was discovered that despite the claims made by the government of India and its defense ministry in the recent past, a large number of educational buildings are still either under direct military occupation or surrounded by their camps and bunkers, distracting students and causing a disruption of their daily activities in school. Out of the thirty schools randomly selected for the survey across the valley, seventy nine percent (79%) were at a distance of less than one kilometer (1km) from the nearest military camp/bunker. In fact, some of the schools share a common border with the camps. While twenty percent (20%) of them were just 2-3 kms away from the nearest military camp and one percent (1%) was partially occupied by the military or Para-military troops.

A military camp in front of school and students are being used by the military to buy cigarettes etc. from the markets.

Due to the presence of a military camp next to my school, which still exists there, we always feel threatened and scared. We were not allowed to play in the school ground as they (military personnel) could see us from the building that they occupy, and pass abusive comments or make obscene gestures.[vi]

The thick presence of the army in the residential areas has serious ramifications including sexual violence, insecurity, abuse and other sorts of harassment. Unfortunately, girls are more vulnerable to the adverse consequences of militarization of educational spaces.[vii] As a result, there has been an increase in the dropout rate among school going children, particularly girls.

Samir Ahmad, is a PhD Research student at the University of Kashmir.

[i] See, Seema Kazi, Between Democracy and Militarization: Gender and Militarization in Kashmir, New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2009

[ii] Oberoi Surinder Singh, Kashmir is Bleeding, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 53, no. 2, March-April 1997

[iv] Kiothra, Verghese, Crafting Peace in Kashmir, New Delhi: Sage, New Delhi, 2004, p. 71

[v] See, Kashmir: A Land Ruled by the Gun, Report by Committee for Initiative on Kashmir, New Delhi

[vi] Interview with a student (May, 2010)

[vii] See, HRW: Everyone Lives in Fear: Patterns of Impunity in Jammu and Kashmir, September, 2006

Hadeel Qazzaz

Dr. Hadeel Qazzaz, Program Director-Pro-Poor Integrity in Integrity Action. She was born in Gaza Shati refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, a specialist in gender and development. She received her Ed.D. from Leeds University. Qazzaz has contributed to the first Palestinian human development report, the Palestine national poverty report, the Palestine time-use survey, and reports on the right to education. She was involved in the adaptation of the Transparency International Source Book into Arabic.

She worked for 10 years as the program manager and deputy director of the Heinrich Boell Foundation in Ramallah. This enriching experience has enabled her to work closely with researchers and activists from many Arab countries and Germany. She is an activist in the Palestinian women’s movement and active member in the Palestinian civil society movement. She is involved in different types of cultural dialogue and exchange including dialogue between Europe and the Middle East. She has organized and has participated in many regional and international conferences that dealt with issues of development, women’s rights, and democratization processes. Currently she is a board member of the Women’s Affairs Technical Committees and the General Union of Palestinian Women, Ramallah branch

Education in Reconstruction- What is missing?

By

Hadeel Qazzaz

While thousands of Palestinians were celebrating the victory of a young Gaza singer in the popular competition “Arab Idol” the Middle Eastern version of American Idol, local news in the Gaza Strip was circulating the death of two young women committing suicide. The two women claimed their lives after failing to answer “Tawjihi”- end of school exam. The sad news did not stop many people to think of the reasons behind such emotional pressure that lead these young women to end their lives.

Living under one of the longest siege and isolation in modern history, education seems to be just one step to escape and move forward. The psychological pressure as a result of Israeli military aggression, poverty, restriction of movement and restriction of freedom of expression, is topped by traditional end of the year exam pressure. An exam which is very competitive and its results are publicly announced, which adds to the social pressure on young students. The results of the Tawjihi usually determine not only which college you can enroll in but also what subject you can study.

With one in 5 persons in Gaza falling under the “youth” category (between 15 and 24 years of age), university education is under enormous pressure to provide education and training opportunities. However, moving to college in the Gaza strip is not really a step in a person’s career. The limited number of specializations, the limited education resources and the traditional methods of education make it an extension of an over-run and over-crowded high school education. Even Mohammad Assaf, the Arab Idol himself could not study music in the Gaza strip and could not leave to study abroad because of travel restrictions on young people his age, compounded by limited financial resources available to support talented students.

At the same time graduation from university does not guarantee that a person will have access to better job opportunities. What is it that led these two young women to kill themselves? It is possibly because of the accumulation of psychological and emotional pressure, or to delay an arranged marriage or to delay unemployment. The youth unemployment in the Gaza strip is very high. The rate for the 15-to-19-year age group reaches 72%, while unemployment affects 66% of those aged between 20 and 24 years. In Gaza, 32% of men between 15 and 24 years participate in the labor force, but the rate is considerably lower for women in the same age group, 7%.

In all cases and despite all the criticism for deteriorating education system in Palestine, education is highly regarded and much valued by Palestinian families. It is still the best available way to improve one’s status and well-being. After all not all young talented people have a chance to become Arab Idols and escape the restrictive norms of society. For young women university education is even more important because of the gender stereotype of what is acceptable for women. Young men can work in any available job, including life-threatening jobs in the underground tunnels that connect Gaza strip with Egypt (and often used for smuggling people and goods of all types). Young women can only work in certain sectors such as education and health services which require a university degree.

In conflict and war-zone areas, like the Gaza strip, education falls under pressure of fulfilling the demands for social and physical reconstruction. However, the consequent psychological and social pressure is largely ignored. Young people need to view the liberating opportunities of education more positively and with less pressure. The education system itself needs to be reformed in a way that accommodates the new needs of post-war communities. Addressing psychological pressure, fulfilling demands for new types of training and marketable skills, and identifying talents that can serve longer-term stability are only few components that need to be taken into consideration.

Dr. Hadeel Qazzaz, Program Director, Pro-Poor Integrity in Integrity Action.

Karen Ross

Moving Beyond Outcomes – Thinking About the Broader Impact of Peace Education in Conflict Zones

By

Karen Ross

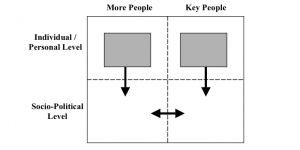

I was inspired, years ago, when I first encountered the Reflecting on Peace Practices (RPP) project at CDA Collaborative Learning Projects , and was particularly struck by a diagram I encountered in one of the project’s publications: Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners. The diagram (below) encapsulates what, for me, is the essence of assessing the ‘impact’ of peace building interventions: a need to link changes among individual participants to larger groups and to change at the socio-political level.

I found this diagram (and the publication as a whole) inspirational because it resonated with questions I had been trying to answer for a while: what difference do grassroots programs bringing together youth in conflict contexts make? How do we know whether these programs have an impact – on individual participants, on other individuals, and on conflict-affected contexts as a whole?

In my years as a scholar and practitioner of dialogue and peace education, I have read a lot of research attempting to answer these questions. This scholarship has taught me a lot, but I also am frustrated by the focus most of it places on examining impact in a relatively narrow manner: as cognitive or attitudinal change measured over a few months. This is not to say that such research is not valuable – in fact, most studies are methodologically rigorous and provide useful information about the potential of peace education programs to change (or not) the perceptions of individuals who participate in them. In other words, this research is important in helping us understand the short-term cognitive, attitudinal, and even to some degree behavior change facilitated by participation in peace education endeavors. Still, what is missing is an understanding of how these changes fit into the bigger picture – that is, whether and how organizations implementing peace education achieve their goals of contributing to a more just and peaceful society.

This is where the diagram from Confronting War comes in. Indeed, much of the field of conflict resolution, the Reflecting on Peace Practice project included, has taken a broader turn in defining and assessing impact that I think can also benefit research focused more specifically on peace education. For instance, conflict resolution scholars have suggested indicators of broader change such as: increased demands for peace by groups of individuals; adoption of ideas from conflict resolution interventions into official negotiations; and continued, specific actions by participants in conflict resolution programs that focus on responding to the needs and concerns of the other side.

Of course, we can’t expect programs targeting school-aged children to show a direct link to changes in government negotiating positions. On the other hand, we can examine and learn from the long-term activities of peace education participants. A recent project of mine, for instance, focused on involvement of Jewish and Palestinian citizens in activities promoting Jewish-Palestinian partnership, as assessed years and decades after their participation in one of two Israeli peace education programs. I found that approximately half of these individuals (65% from one of the two programs, and about 40% from the other) are actively involved with other dialogue initiatives, peace-building organizations, or activities that focus on changing Israeli society to be more equitable for all of its citizens. Even after all these years, many pointed to certain aspects of their participation in the peace education programs as inspiring their later actions. Some spoke about acquiring political knowledge that inspired them to think critically about Israeli society and work to change it. Others mentioned being inspired by seeing equality between Jews and Palestinians modeled among program staff – seeing this gave them hope that such equality might someday be possible in Israeli society, and motivated them to work towards that reality. One woman told me that her peace education participation “changed my life,” and is the primary reason why she has the career she does today.

It is clear that for many alumni of at least these two peace education programs, participating in joint Jewish-Palestinian endeavors as youths played a major role in their decisions to undertake additional activities that emphasize the pursuit of peace and justice. And while it’s not possible to generalize to all peace education programs, this finding is important because it suggests that peace education initiatives can not only set the stage for long-term change among their participants, but that the nature of that change builds into other peace-building efforts in societies suffering from conflict – suggesting that these programs have a broader impact than what scholarship to date has noted.

There is much more that can be said about this. For now, let me end by reiterating that I believe we need to think much more broadly about what constitutes impact and how it might be assessed. Only by doing so can we know the true value of peace education endeavors.

Karen Ross recently completed her PhD in Inquiry Methodology and International & Comparative Education at Indiana University, where she continues to teach as a research methodology instructor.

[KR1]Link: www.cdainc.com

Kevin C. O’Dowd

Kevin C. O’Dowd has been working in the documentary field for over 7 years. He has worked with Google, CNN, Travel Channel, NOVA, MacArthur Foundation, Kartemquin Films (Hoop Dreams) and many other documentary companies from around the world. Together with the Norwegian Refugee Council Colombia, Kevin produced a short documentary film focused on ‘Education in Emergencies’ in a rural village on the Pacific Coast of Colombia. Kevin worked in Colombia for nearly two years as the Program Manager for the Bilingual Educational Program at Colegio Santa Ines, were he spearheaded the inception of the program. He also taught his students media literacy, photography, and video production.

Kevin holds an advanced degree from the Center for Global Affairs at New York University, with a concentration in humanitarian assistance and international development and a Bachelor of Arts degree in film and video from Columbia College.

Stopping the Shakiro: How an ethno-high school in Colombia stands up against armed conflict

The following is an interview with Kevin C. O’Dowd, Director of Stopping the Shakiro. This compelling 22 minute documentary tells the story of two female students who attend the Ethno-High School in the rural village of Chajal, outside the city of Tumaco in South-West Colombia. Chajal is primarily comprised of Afro-Colombians who are disproportionately affected by Colombia’s 5 decade-long armed conflict. As a result of the conflict sensitive and ethno-centric curricula, taught at the ethno-high school,the two students share with us their transformative experience as the audience learns what it is like living alongside armed conflict in Colombia.The film weaves in key stakeholder interviews from INEE, UNICEF, Save the Children, NRC and ECHO.

1. What drew you to make a film about this population?

I was curious about why the Afro-Colombian population is disproportionately affected by the armed conflict. The Afro-Colombian population lives on the Pacific Coast in the western parts of the Andes mountain range. They receive very little support from the Colombian government and I wanted to explore what the people of this community actually thought of this negligence. However, I found it extremely challenging to delve further on the subject. As one can imagine, this is a very contentious issue, as the iNGOs working with this population have to work with the Colombian government and therefore have to be diplomatic when expressing their opinion regarding what the government is doing on the ground. All of the Afro-Colombian interviewees in the film, including ones in the government, spelled out reasons why the government’s support does not reach their community. In my opinion, the Colombian government is trying to lend support but for some reason it seems to fall short, when it crosses the Andes.

2. What educational challenges does this population face?

The educational challenges that the Afro- Colombian population, in the Tumaco region, face is the lack of quality education. Other challenges are what one may find in any developing context: young mothers dropping out of school to raise a family; no money to afford school supplies and school uniforms; parents that don’t see the value of an education-some parents can easily understand how fishing will bring in economic security, as compared to an education; the school schedule is not a good fit for the young mothers who have to raise a family; young people don’t see themselves in the text books, the curriculum was not created for their population and therefore they lose interest.

3. Does education address these challenges?

This Ethno-High School does address these challenges. The curriculum was designed and implemented for and by Afro-Colombians living in the Tumaco region. The school schedule is on the weekend, therefore making it easier for parents to raise a family and work during the week and then study during the weekend. The high school’s aim is to create leaders in the community who understand that they have opinions that can be voiced by other means than joining an armed group. The schools are empowering each student with the knowledge of better fishing practice, agro-forestry, and how to confront conflict in a professional and rational manner.

4. Why is this film significant?

This film is significant because it attempts to address the challenges raised in question 1, while at the same time, trying to portray Colombia in good light. We read a lot of negative stories coming from Colombia but there are thousands of positive stories, like that of the Ethno-High School.

5. What questions need further exploring or are contentious in the context of this population?

Questions that I think need further exploring would be to investigate what exactly the Colombian government is doing in these hostile regions that is helping to improve the lives of marginalized populations. This is such a contentious topic because many people in Colombia, and outside Colombia, including diplomats, do not want to address it. What is really at the heart of this problem is racism. Just as in the US, there is substantial racism in Colombia. But there are not a lot of people who want to talk about it. The people on the Pacific Coast are neglected by the state because of their race.

The film is being screened at Teachers College, Columbia University on September 18th, 7:00-8:30 PM. Russell, 306. Screening followed by Q & A with the Director.

Kevin C. O’Dowd, is a Humanitarian Media Professional who utilizes visual storytelling as a communications tool to raise awareness of humanitarian issues and support global efforts to aid programs for countries in need, including Columbia, Afghanistan, and North America. Kevin has an M.S. in Global Affairs from New York University and a B.A. in Film and Video from Columbia College, Chicago.

Kathryn Moore

Kathryn (Katie) Moore is a peacebuilding and international development professional. She has five years of experience working in diverse global organizations throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, the East Asia and Pacific region, and the United States. Her education, peacebuilding, and training interventions have engaged hundreds of leaders and youth in leading organizations within the public sector. Among her most recent work, Kathryn has been named an International Development Fellow for Catholic Relief Services’ Laos country program, has conducted short-term projects for UNICEF’s New York Headquarters’ Performance Management Unit, UNDP Fiji’s Peace and Development Adviser, Amnesty International’s National Youth Program, Columbia University’s Peace Education Network, Save the Children Mozambique, and U.S. Peace Corps Mozambique.

Kathryn has a broad base of experience providing a range of interventions including: facilitation, training, program design, program management, program evaluation, and research design, implementation, and analysis. She has specialized experience in the areas of international family and community mobilization, peacebuilding, youth development, adult learning, and early/middle childhood education. Some examples of recent projects include: 1) designing and delivering a project sustainability and best practices in emergent literacy training for over 100 Mozambican government officials, primary teachers, and local community leaders 2) supporting logistical preparation for Amnesty International USA’s nation-wide annual youth training for over 100 youth and designing/analyzing the training’s survey assessment 3) reconceptualizing monitoring and evaluation for peacebuilding purposes with the UNDP Fiji’s Peace and Development Adviser 4) supporting all aspects of UNICEF’s Performance Management Unit (PMU) including drafting a survey deployed to 700 staff worldwide on their experiences as part of a Soft Skills Workshop program and revising/creating PMU materials for UNICEF staff and external stakeholders.

Kathryn’s Master of Arts degree from the Department of International and Transcultural Studies at Teachers College, Columbia University was conferred in February 2013. Kathryn has a B.A. in Early/Middle Childhood from Butler University in Indianapolis. She is in the process of transitioning to her new role as a fellow in Laos.

Critical Participatory Action Research as a Potential Intervention and Approach in Conflict Transformation Processes

By

Kathryn Moore

Why do organizations solicit participation from “local stakeholders” when the people exist there already, creating movements and advocating for themselves?

This was the question of one development practitioner who witnessed people’s power and their movements for social change, as they were the “owners of the issue” after a natural disaster in her home country (anonymous, personal communication, July 10, 2013). The practitioner determined that her emergency response, even within her home country, was not humble enough due to the inherent power she held as an “insider” in the country but still an “outsider” to those affected in the fragile context. This example highlights how “participation,” a buzzword in the international development and peacebuilding fields, becomes problematic when it reproduces inequalities within groups and reinforces power hierarchies between “outsiders” and “insiders” by showcasing external interests as local concerns and needs (Cooke & Kothari, 2001).

In another instance, a peace and development practitioner noted how women and children died as a result of not being able to swim during a natural disaster. Women and their communities requested swimming instruction specifically for women; however, international practitioners maintained the true problem was lack of women’s human rights access. After much debate, women received training from local professional female swimmers (personal communication, July 18, 2013). This process led the practitioner to question whether international practitioners, donors, communities and organizations, working together, are capable of realizing true participation when not genuinely considering how communities define what it means to “participate” and define their own issues (personal communication, July 18, 2013).

How can initiatives in development and peacebuilding contexts, with the aim of conflict transformation, be truly inclusive, participatory, and more than short-term development projects (as cited in Lederach & Jenner, 2002)? How can those most impacted in said contexts be the “owners of the issue(s)” as well as actively engaged in developing and realizing solutions over time? I posit that as an intervention, Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) allows minority groups to drive their own conflict transformation processes in fragile contexts as well as exemplify “true” participation of local stakeholders in development initiatives. CPAR, as defined by colleagues from the Public Science Project (PSP), is “a framework for creating knowledge that is rooted in the belief that the most impacted by the research should take the lead in framing the questions, design, methods, analysis and determining what products and actions might be the most useful in affecting change” (Torre, 2009).

CPAR assumes that all people and institutions are embedded in complex social, cultural, and political systems historically defined by power and privilege and that social research is most valid when using multiple methods (Torre, 2009). The latent conflict context of Fiji is an example of one place where CPAR has potential to simultaneously “remember bodies, knowledge, histories of resistance, and opposition that has been excluded” while serving as a conflict transformation intervention (Torre, 2009). Youth have typically been marginalized in peace and development processes with Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) offering the most genuine outlet for youth participation in peacebuilding and conflict transformation (Gavidi & Moore, 2012). If CPAR were employed as a framework, youth, a traditionally “forgotten” or excluded body, may potentially participate in the entire research process from the inception of framing the questions to determining products and actions, thus allowing for conflict transformation of the individual youth within CPAR and society at large. Regarding methodology, if Fijian youth choose to do focus groups as one method in a mixed-methods approach, they could involve more non-formal traditional ceremonies such as the kava ceremony, a ceremony involving drinking the traditional relaxing drink that used to be reserved for indigenous chiefs. This would allow for potential understanding of the “other,” thus embarking on a process of truth and reconciliation between multi-generational and inter-ethnic groups, while simultaneously systematically researching youth as peacebuilders in the process.

CPAR maintains that participation is along a continuum, contextualized and that there is not one “right” way to determine what participation may look like in a given setting or institution (Dr. Maria Elena Torre, personal communication, June 20, 2013). Clara Hagens, a Regional Technical Advisor for Catholic Relief Service’s (CRS) Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning and Accountability (MEAL) in Asia, noted the continuum of participation within the organization, which has peacebuilding as one of its thematic areas. Hagens asserted that examples of significantly participatory initiatives are when communities have designed the project in partnership with the organization’s staff, designed and determined indicators to measure success in the project’s process and outcome, led data collection efforts, and analyzed/determined what actions to take with evaluation findings. An example of participation included a project where CRS and partner institutions determined a desired change and the community defined the “nuts and bolts of the behavior change and what success would look like to them” (Clara Hagens, personal communication, July 15, 2013). Hagens provided a critical perspective on the participation continuum and stated that while there is a commitment to participation across the organization, how it is managed varies greatly related to time and resources in various locations. The question remains as to how, in conflict transformation processes that are very context specific, continuums of participation may be considered when the organizations, themselves have specific norms.

Another example of the continuum of participation comes from a USAID development practitioner working in a post-conflict setting, wherein local university students and government ministries’ officials partook in the data collection process over a six-week period (USAID practitioner, personal communication, July 17, 2013). The local practitioners were able to witness issues in development “on the ground” that allowed them to become “insider” advocates for issues at hand instead of relying solely on “outsiders’” research and perspectives on development issues (USAID practitioner, personal communication, July 17, 2013). The local practitioners requested USAID’s support to build local data collection and analysis skills, among other skills, in order for locals to be the principle leaders in their own research processes over time (USAID practitioner, personal communication, July 17, 2013). Conflict transformation processes include the idea of “continuums of participation” when outsiders are facilitating peace processes; how much of the participation should be “insiders” vs. “outsiders” is a question that remains in both CPAR and conflict transformation processes alike.

CPAR holds that participation might not happen instantaneously and believes relationships are constructed over time (Torre, 2009). Education for Peace (EFP), an NGO working in post-conflict Bosnia-Herzegovina, provides an example of participation evolving over time in conflict transformation processes. Naghmeh Sobhani, working with EFP for over twelve years, noted that, in “true” participatory processes, “the ‘circle of participation’ is expanded over time” (Naghmeh Sobhani, personal communication, July 12, 2013). More people subsequently want to be included and put their “own piece into the group effort.” Sobhani also noted the importance of relationship construction over when working with multiple groups (i.e. ethnic groups, groups with different levels of authority, etc.). Multiple groups needed to first have their own affinity groups in which to set the climate and agenda prior to working in shared spaces. Instead of EFP staff being the “process-owners,” former members of the affinity groups explained to newer members of the plenary the mechanisms for how the group exercises participation that had been co-created and practiced by the plenary over time. Affinity groups later forming a plenary over time might be a timely process based on the traditional age hierarchy of society, ethnic violence, and structural inequalities; however, as with EFP’s example, relationship construction with evolving groups over time could lead to participatory efforts’ long-term ownership and sustainability.

The examples highlighted suggest CPAR is both an approach and an intervention in conflict transformation processes. However, significant considerations and dilemmas ensue. Some deliberations are the ethical considerations around determining issues to be researched and identifying participants to be involved in CPAR, how to ensure that the continuum of participation is reflected upon across institutions with multiple international locations, the readiness of organizations and the donor community to accept longer-term “true” participatory processes vs. quick-impact projects, and how to realize the diversity of groups most impacted inclusion in CPAR efforts, especially when some important groups are resistant to join research efforts. Finally, how may groups prove with their research, in fragile contexts where some fractures might still exist, that conflict transformation is taking place within ongoing, timely processes utilizing CPAR?

Kathryn Moore is an International Development Fellow 2013-2014, Catholic Relief Services Laos.

References:

Cooke, B. & Kothari, U. (Eds.) (2001). Participation: The new tyranny? London: Zed Books.

Gavidi, K. & Moore, K. (2012). “Invented traditions: youth as peacebuilders in collaboration with civil society organizations in Fiji.” (Unpublished M.A. thesis). Teachers College, Columbia University, New York. Retrieved from https://www.dropbox.com/s/lbg5h0d7spc28up/Invented%20Traditions-Youth%20as%20Peacebuilders%20in%20Fiji.FINAL.pdf

Lederach, P. & Jenner, J. (Eds.) (2002). A handbook of international peacebuilding: into the eye of the storm. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Torre, M. E. (2009). Principles of critical participatory action research. Retrieved from http://www.publicscienceproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/PAR-Map.pdf