Transatlantic Constructions of American Identity in the Global Climate Context (1988-2011)

Wednesday, April 17th, 2013

Introduction: Theory and Research Problem

While global climate change is widely regarded as a significant “global problem [that requires] global solutions,” it is striking that policymakers and scholars alike continue to diverge over a common definition of the problem. [i] The lack of a definition impedes efforts to develop an effective global climate change regime that is capable of eliciting international support.[ii] Indeed, the absence from the Kyoto Protocol of the largest polluter—the United States, which boasts significant resources to combat atmospheric degradation—comprises a major impediment to the global climate regime.[iii] Traditional theories of international relations—namely neo-realism, neo-liberal institutionalism, and structuralism—account for American abstention from the Kyoto Protocol by prioritizing materialist and utilitarian determinants of U.S. foreign policy.[iv] This view depicts the United States as a selfish, powerful, and irresponsible accomplice in global climate change that prioritizes its national economic interests over those of the international community. Such thinking is also prevalent in the media, which is demonstrated by merely citing some of the labels that are assigned to the U.S. in the climate context such as “laggard instead of leader,” “the world’s largest polluter,” “major contributor to the global warming problem,” and “isolated…arrogant.”[v]

However, by prioritizing its nonparticipation in the global climate regime and national economic interests over more constructive American contributions—such as its state-level climate initiatives, provision of significant funding for scientific research, and development of clean technologies—such approaches overlook significant nuances in U.S climate policy, which are suggestive of a more progressive and legitimate character. [vi] In order to transcend the traditional narrow focus on material determinants of international environmental politics that depict the United States as a static irresponsible actor in the climate scene, this study posits the need for a more comprehensive analysis of American climate identity in its own right and poses three fundamental research questions:

- What are the salient strands of the U.S. image, in the climate context, as manifested in the American and European media?

- What kind of sentimental or normative image do they construct for the United States?

- How does U.S. image vary:

- Contextually across transatlantic—European and American—media sources.

- Temporally with respect to important developments in environmental diplomacy and different American presidencies.

In this endeavor, the growing body of social constructivism literature—which draws attention to the social ontology of world politics and, more specifically, to the concept of identity in the global climate context—informs the following discussion.[vii] Proceeding from a social constructivist appreciation of identity, this study employs computer-assisted content analysis (CCA) of American and European newspaper coverage of the United States in the climate context in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of American climate image by disaggregating its fundamental dimensions and tracing dynamic variations in their saliency and valence across two contexts, namely:

- Transatlantic media sources

- Important developments in international environmental diplomacy and different periods of American Presidency.

The following section describes the assumptions and hypotheses that inform the approach of this study, which provides the foundation for the selection of methods and data, which is the focus of the third section. Lastly, the study presents the findings and draws analytical conclusions to the research questions.

Approach and Hypotheses

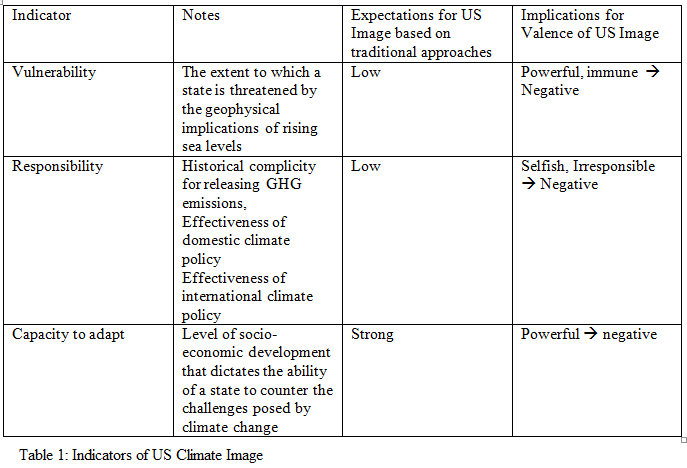

Both the literature relating to climate politics and an inductive reading of the 113 newspaper articles that the author collected and analyzed for the purposes of this study informed the delineation of three salient dimensions of U.S. identity in the climate context: vulnerability, responsibility, and capacity to adapt to climate change—see Table 1. Indeed, while numerous scholars identify states in the climate context as northern or southern based upon their levels of geophysical vulnerability to climate change, and socio-economic development—which is indicative of their capacity to adapt to rising temperatures—the global climate regime itself also categorizes countries as Non-Annex or Annex-A to indicate their status as developing-developed countries respectively.[viii] While a combination of high vulnerability and weak capacity to adapt are already suggestive of a legitimate state that may be normatively entitled to assistance from less vulnerable and stronger members of the international community, the domestic and foreign climate policies of states are frequently regarded as indicative of national environmental responsibilityand therefore bear great influence over the legitimacy of actors in the climate arena.[ix] Thus, the first hypothesis of this study argues that the aforementioned indicators comprise effective measures of the content and saliency of U.S. image such that:

Table 1: Indicators of U.S climate image

Secondly, given the influence of political actors over the media, this study further hypothesizes that European newspapers will be more critical of U.S. climate policy relative to their American counterparts. This delineation is particularly relevant in the American context in which it experts such as Harris assert that the government controls the media. Resultantly, this study expects to find that American newspapers afford greater emphasis to the more positive aspects of U.S. performance in the climate context.[x]

Methods and Data

Two methods of CCA were combined with hand-coding to identify and trace dynamic changes within the salience and valence of the three strands of American climate identity relative to the source of the newspaper and temporal developments, namely Lexis-Nexis article searches, Yoshikoder word scoring, and manual sentiment analysis.

Firstly, the Author utilized the Lexis-Nexis database as a comprehensive search engine to select 113 articles pertaining to U.S. involvement and climate change from American and all English speaking European newspapers. The decision to sample articles from newspapers located across both sides of the Atlantic rests upon the aforementioned second hypothesis. That is, the inclusion of domestic American newspapers allows for a more sensitive and disaggregated analysis of the three strands of American climate identity by maximizing the potential to detect positive nuances that contradict traditional approaches. Similarly, by virtue of their relative distance from U.S. policymakers, European newspapers were expected to demonstrate more negative imagery of U.S. climate identity, which is more compatible with the traditional approaches discussed during the introduction.

Therefore, and noting the space constraints of this essay, the sample of articles was delineated by employing the search terms: “USA*” or “United States*”, and “climate change*” or “global warming*”, which was further limited by searching for terms appearing exclusively in headlines and excluding high similarity duplicates and newswires.

Given the relatively recent ascendancy of climate change to the political agenda, the study placed no lower time limitations on the article search. The study excluded articles published after 2011 to prevent underestimations of saliency and valence for articles published in 2012.[xi]

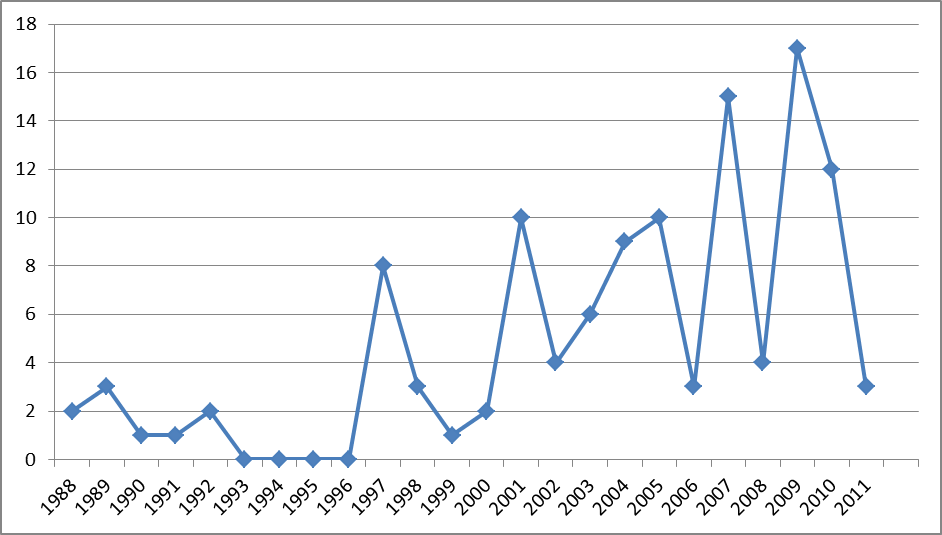

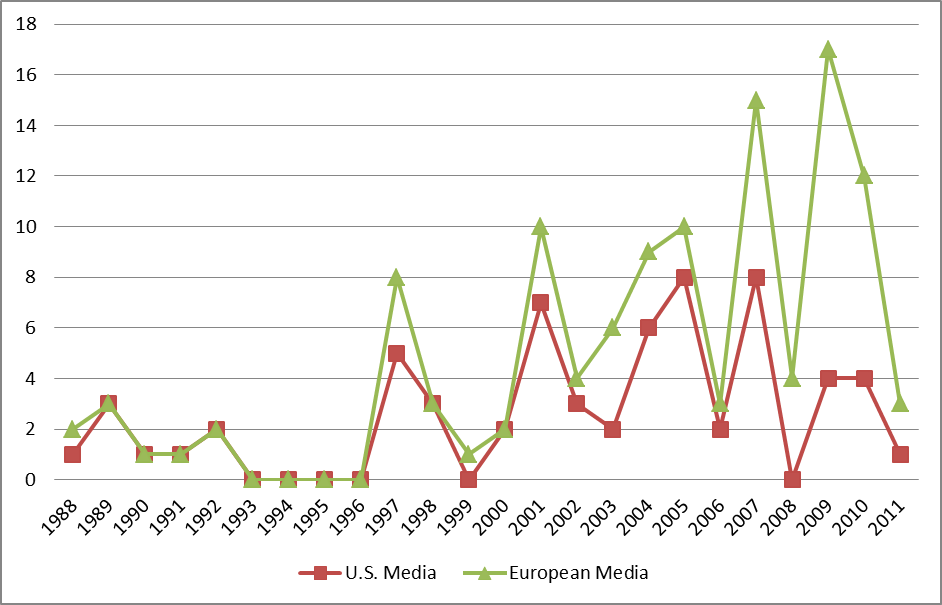

As illustrated by Figures 1 and 2, 113 articles conformed to the search criteria, consisting of sixty-one articles from the U.S. media and fifty-two from English-language European newspapers. Figure 2 demonstrates that although newspaper coverage of the United States and climate change has gradually increased on both sides of the Atlantic, European coverage has exceeded that of its American counterparts since the late 1990s, which coincides with the period of heightened international environmental cooperation that resulted in the Kyoto Protocol.

Figure 1: Total number of retrieved articles by year

Figure 2: Number of U.S. and European articles by year

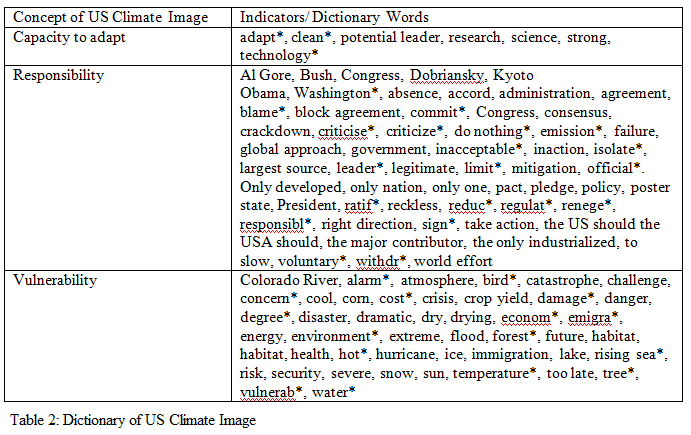

Secondly, drawing on the methodology employed by Sullivan and Lowe, this study assumed that the operationalization of social constructivist identity is feasible by delineating three concepts of U.S. climate image, which are observable through recording the frequency of various word patterns—i.e. wordscoring—that comprise indicators of U.S. vulnerability, responsibility and capacity to adapt.[xii] Thus, after delineating the sample of articles from Lexis-Nexis, each article was converted into text-format to allow for quantitative content analysis of words-pattern frequency using the Yoshikoder software package. In keeping with the approach of Mawdsley, the articles were read inductively to identify common word patterns that were repeatedly indicative of the three concepts. From the inductive reading, the following dictionary of U.S. climate image indicators was developed and subsequently correlated with the content of the sampled articles through the production of unified Yoshikoder reports.[xiii]

Table 2: Dictionary of U.S. climate image terms

The article comprised the natural unit of coding, which was analyzed twice for content/salience and sentiment/valence. The study then contextualized the articles to account for the influence of newspaper sources, important developments in multilateral climate diplomacy, and differences among American presidencies. This report provides a full description of the methods of analysis used to address each research question in the following discussion of results. Through a comprehensive and systematic textual analysis of articles, this study was able to indirectly observe U.S. identity in the climate context in a transparent and replicable manner that is readily applicable on a larger scale.[xiv]

Analysis of Results

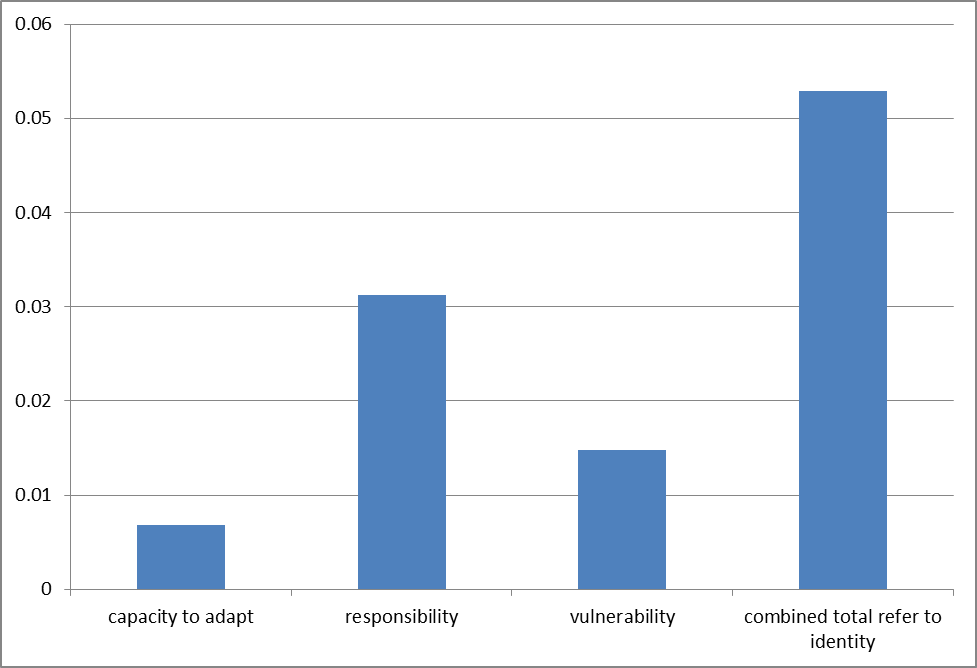

In order to address the first question regarding the salience of the three dimensions of American climate identity in U.S. and European newspapers, the frequency of mentions of capacity to adapt, responsibility and vulnerability were coded for each article and then calculated as a proportion of the word count of each entry. The far right column—the combined total—of Figure 3 demonstrates that although the proportions involved are small in that on average, the dictionary indicators comprised approximately 5 percent of the entire 113 articles, responsibility comprised the most salient dimension of U.S. climate identity in the sample.

Figure 3: Salience of U.S. climate image in U.S. and European newspapers

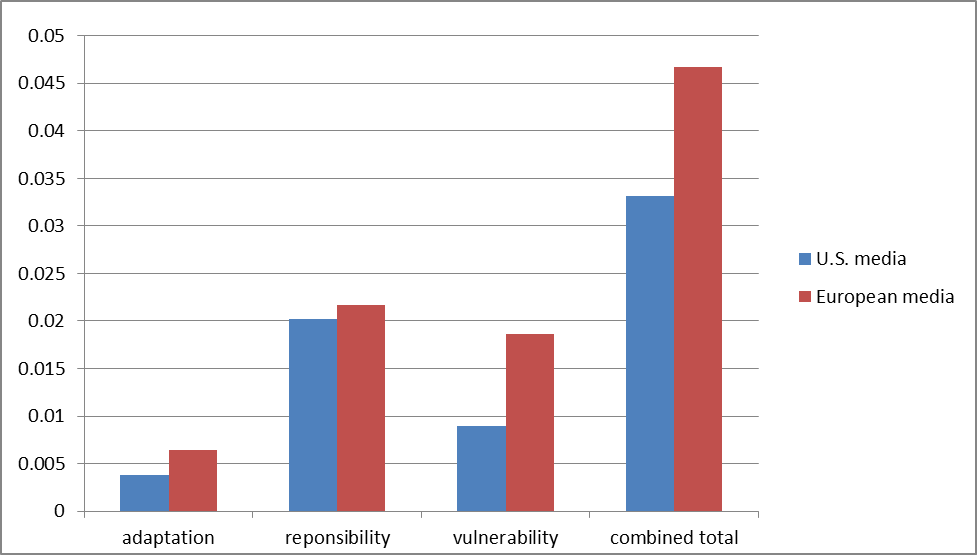

The study notes that by presenting the average salience of the three concepts of U.S. identity across U.S. and European media sources and the period from 1988-2011, Figure 3 merely provides a snapshot of the content of American image in the climate context. Figure 4 disaggregates the salience of these dimensions to account for variations across transatlantic media sources. The disaggregation demonstrates that on average, European newspapers consistently afforded more salience—manifested by higher proportions of mentions—to all three dimensions of U.S. identity than manifested by their American counterparts.

Figure 4: Disaggregated Saliency of U.S. climate image across U.S. and European newspapers

Having demonstrated that responsibility comprises the most significant element of U.S. climate image across U.S. and European newspapers, and European articles consistently afford more saliency to all three dimensions of American climate identity, there is a need for a deeper analysis of the implications of the three strands of identity to ascertain how:

- Adaptation capacity, responsibility, and vulnerability may possess different sentimental connotations for U.S. and European newspapers

- Their valence varies temporally in relation to important developments in international and domestic political developments.

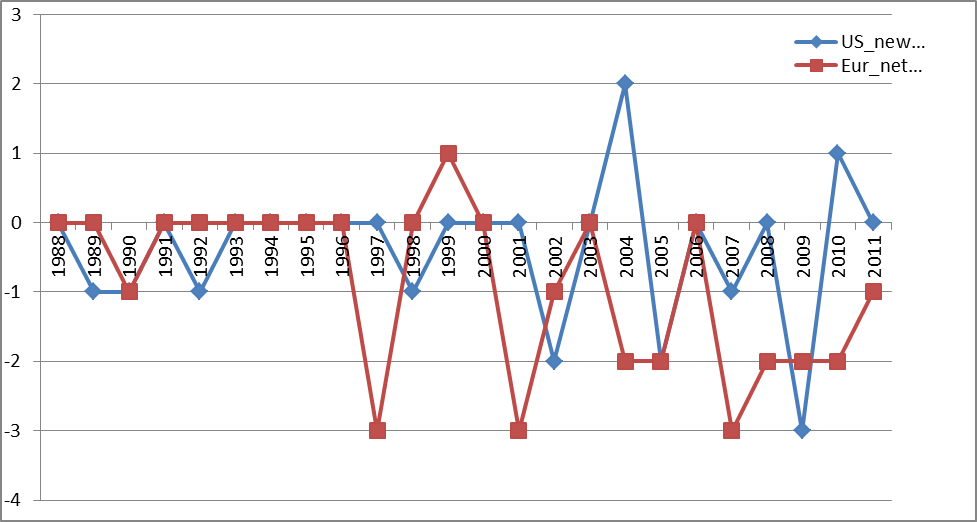

In this endeavor, each article was reread to allow for hand-coding of the valence of mentions of the three identity dimensions, which facilitated a deeper, critical analysis by acknowledging that, although U.S. and European articles may afford similar salience to each concept—as detected by CCA—their sentimental connotations could be contradictory. Therefore manual analysis is necessary on grounds that it is more sensitive to normative nuances.[xv] Drawing on the first hypothesis, the study coded strong capacity to adapt, irresponsible behavior, and low vulnerability as negative mentions, with a value of negative one. The study coded sentimental references to the same indicators as positive mentions, with a value of one, and non-mentions as neutral mentions, with a value of zero. This way, it was possible to transcend the simplistic analysis of saliency based on frequency of mentions and quantify the sentimental connotations of temporal references to each concept across U.S. and European newspapers by calculating the cumulative values of mentions for each year—see annex A.

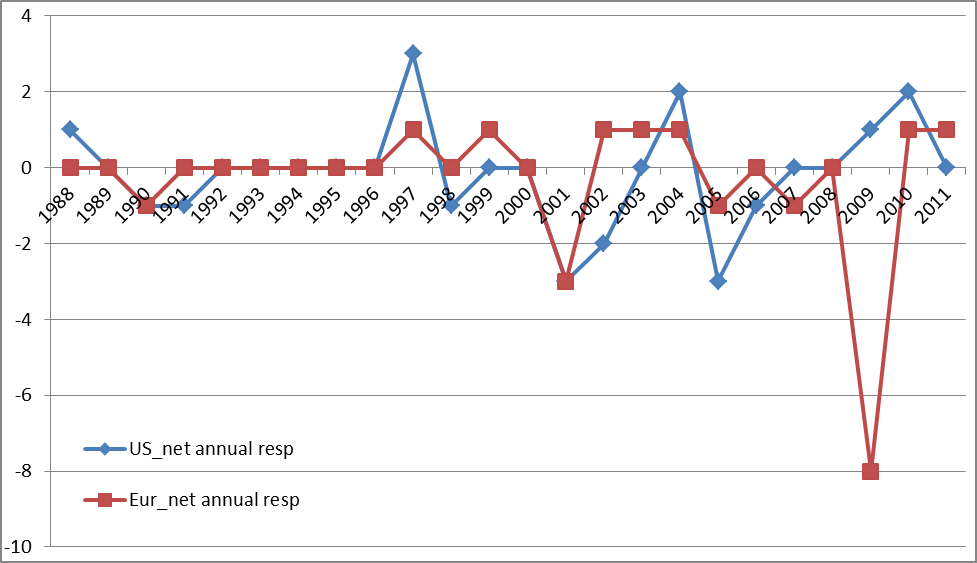

Figure 5 demonstrates that European appraisals of U.S. responsibility were generally less positive than the appraisals by their American counterparts. This is particularly striking since 2007, after which time the European conceptualizations of responsibility have assumed negative connotations in contrast to positive appraisals by U.S. newspapers. While U.S. articles generally conceptualized responsibility in positive terms, by referring to American environmental conscientiousness and effective domestic climate policies, European references to responsibility tended to focus more on the failures of U.S. foreign climate policy. Therefore, despite the fact that European articles afford greater saliency to responsibility—see Figure 4. Figure 5 demonstrates that the normative connotation of this emphasis is predominantly negative in contrast to the less salient but largely positive coverage by U.S. papers.

Figure 5: Valence of U.S. responsibility as a component of U.S. climate image in U.S. and European newspapers from 1988-2011

Conclusions

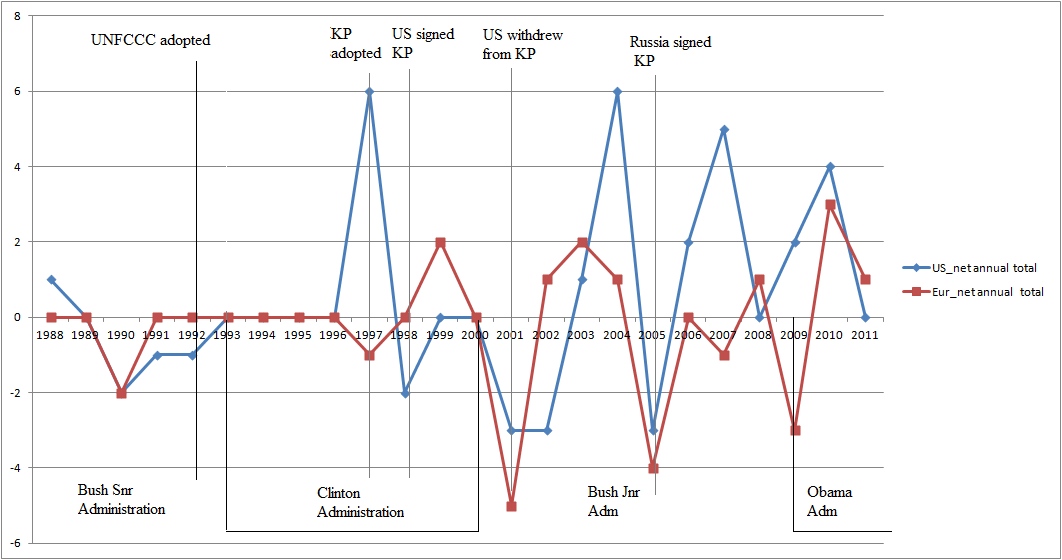

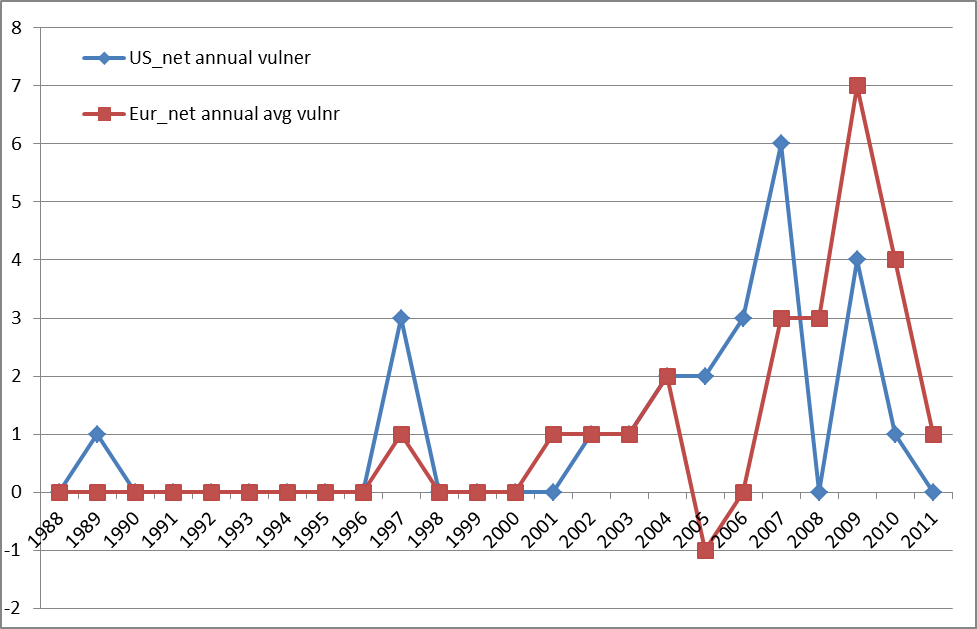

After demonstrating that 1) the three dimensions of U.S. image are meaningful, responsibility is the most salient, and 2) the source of the newspaper is significant in assigning sentimental meaning to salient concepts of U.S. identity, one can draw three further conclusions from a temporal analysis of variations in the combined concepts of U.S. image. To this end, Figure 6 aggregates the net sentiment codes for each strand of identity to illustrate variations in valence relative to key developments in international environmental diplomacy and U.S. presidencies. [xvi] First, developments in international environmental diplomacy are significant determinants of U.S. identity in the climate context, particularly in the construction of negative imagery. When the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997, the positive spike sentiment is less extreme than the negative sentiment that accompanied the United States’ withdrawal from the climate protocol in 2001. Russian participation, which facilitated the Kyoto Protocol to enter into force in 2007, further reinforced the spike in negative sentiment associated with the U.S. withdrawal. Furthermore, the political orientations of U.S. presidencies comprises a second significant factor of U.S. identity, such that one can observe more negative sentiments under Republican administrations, with more positive appraisals under Democratic administrations. Lastly, one can conclude that regardless of developments in international diplomacy or American politics, U.S. coverage is generally more positive of U.S. climate identity when compared to the coverage by its European counterparts. This attests to the presence of media bias.

Figure 6: Temporal variation of U.S. climate image

Annex A: Valence Coding of Strands of American Climate Identity in U.S. and European Articles

|

US Media

|

European Media

|

|||||||

|

Year

|

Annual Capacity

|

Annual Responsibility

|

Annual Vulnerability

|

Net Annual Total

|

Annual Capacity

|

Annual Responsibility

|

Annual Vulnerability

|

Net Annual Total

|

|

1988

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1989

|

-1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1990

|

-1

|

-1

|

0

|

-2

|

-1

|

-1

|

0

|

-2

|

|

1991

|

0

|

-1

|

0

|

-1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1992

|

-1

|

0

|

0

|

-1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1993

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1994

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1995

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1996

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1997

|

0

|

3

|

3

|

6

|

-3

|

1

|

1

|

-1

|

|

1998

|

-1

|

-1

|

0

|

-2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1999

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

|

2000

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

2001

|

0

|

-3

|

0

|

-3

|

-3

|

-3

|

1

|

-5

|

|

2002

|

-2

|

-2

|

1

|

-3

|

-1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

|

2003

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|

2004

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

-2

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

|

2005

|

-2

|

-3

|

2

|

-3

|

-2

|

-1

|

-1

|

-4

|

|

2006

|

0

|

-1

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

2007

|

-1

|

0

|

6

|

5

|

-3

|

-1

|

3

|

-1

|

|

2008

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

-2

|

0

|

3

|

1

|

|

2009

|

-3

|

1

|

4

|

2

|

-2

|

-8

|

7

|

-3

|

|

2010

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

4

|

-2

|

1

|

4

|

3

|

|

2011

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

-1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

Annex B: Valence of Concepts of U.S. Climate Image in U.S. and European newspapers from 1988-2011

Figure 7: Valence of U.S. Capacity to Adapt as a Component of U.S. Climate Image in U.S. and European newspapers from 1988-2011

Figure 8: Valence of U.S. Vulnerability as a Component of U.S. Climate Image in U.S. and European newspapers from 1988-2011

Author’s Biography

Zeynep Clulow is currently a PhD candidate at the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham (UK), where she is the holder of a Doctoral Studentship from the European Social Research Council. After graduating as the top ranking student of the Faculty of Economic and Administrative Sciences and the Department of International Relations at the Middle East Technical University in Turkey, she completed a MPhil in International Relations at the University of Cambridge (UK). Her research interests include international environmental politics, theories of international relations, global security, and comparative politics. She presented a paper entitled "A Comparative Study of Political Transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan" at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London in November 2012.