Multimodal Teaching, Zoom Workshop

Event date: December 4, 2020

From Colloquium Co-organizer Diana Newby: A Note about the Event

For many instructors, the shift to emergency remote teaching this year has prompted a reckoning. Not only have we been tasked with adjusting many of our teaching practices, but we’ve also been pushed to reflect on how these practices affect our students and their learning processes. Questions of access and engagement in the classroom are perhaps more crucial now than ever before. How can we ensure that our students are able to fully and equally participate in the online learning environments we create?

One way of approaching such questions is to turn to theories and practices of multimodal learning and instruction. The concept of “multimodality” in pedagogical literature has taken the place of the earlier theory of “learning types,” which held that everyone is a different “type” of learner: visual, auditory, reading/writing, or kinesthetic. Nowadays, the literature suggests instead that everyone learns through multiple “modalities.” As Roxana Moreno and Richard Mayer (2007) explain, modalities are the “sense receptors used to receive information,” such as auditory information – “through the ears” – or visual information – “through the eyes” (p. 310). These modalities correspond to the different “modes” in which information is represented: that is, verbal modes — e.g., printed words, spoken words” — and non-verbal modes — “e.g., illustrations, photos, video, and animation” (Moreno and Mayer, 2007, p. 310).

What this theory implies for instructors is that our teaching approaches, like our students’ learning processes, should be multimodal. An effective learning environment will use multiple modes for representing the course content, enabling students to engage with that content through their own multiple modalities. In particular, scholars like Moreno and Mayer (2007) emphasize the importance of blending the verbal mode of representation, which “has long dominated education,” with various non-verbal ones (p. 310). By making an effort to include non-verbal modes of representation in our classrooms, instructors better ensure student engagement with and understanding of the material we want them to learn.

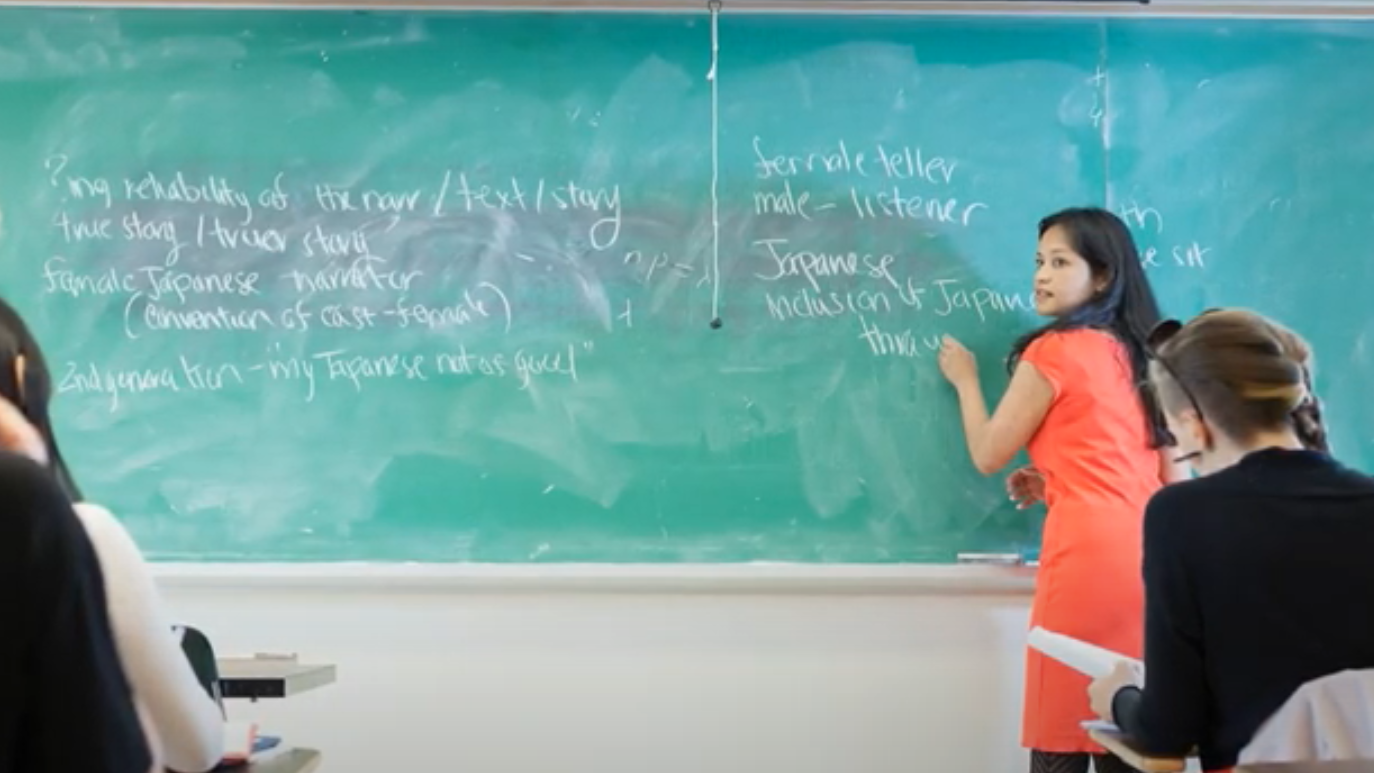

In order to find out more about what multimodal instruction can look like in action, the Pedagogy Colloquium hosted a workshop led by Columbia English Professor Denise Cruz, who has been applying principles of multimodal teaching and learning in her Fall 2020 lecture, “Asian North American Literature.” Below you will find the paraphrased content of Professor Cruz’s presentation and Q&A, followed by a list of tools and resources that she and the Colloquium recommend for instructors interested in improving the multimodality of their classrooms.

From Professor Denise Cruz, Professor of English

I’ve been teaching in university settings for about 20 years. I love working with my students and TAs in the classroom. I also love the process of thinking and learning about teaching. Although like many of you I felt tremendous dismay and panic about transitioning to a virtual environment, I wanted to use the fall to experiment and reflect upon my teaching.

I’m very interested in the lecture as a valuable pedagogical form, in contrast to some arguments about its waning importance. I think the large lecture can be a space for dynamic learning and engagement. It’s an opportunity to foster a diverse community of scholars.

In the past my lectures depended on high level of responsiveness to students. My challenge was how to translate this to the small boxes on my screen. How could I use this moment to think about different learning styles? To think about accessibility?

I had four goals:

- To reformat my delivery within a blended/hybrid learning environment.

- To think about how a virtual environment could encourage me to provide a more effective organization of course material, including clear learning objectives for my students.

- To experiment with multimedia, multimodal learning that reaches scholars and learners at different levels of ability, in different ways (differentiated learning).

- To experiment with enhanced scaffolding, including scaffolding writing methods.

During the Fall 2020 semester, in the lecture I’ve been teaching on “Asian North American Literature,” I have pursued these goals through the following elements of my course design:

The Canvas Home Page

We might assume that our students somehow magically understand 21st century technologies because they’re so-called “digital natives.” But researchers like Michelle Miller have compellingly argued that we shouldn’t make this assumption. It requires executive function and memory processing for our students to learn different systems. Our students might have never seen a learning management system (LMS). They might not be familiar with Canvas. Students who are transferring in are coming to a new system altogether. All of this means that we need to be very careful and deliberate about what we’re doing.

For these reasons, I wanted the landing page of the class Canvas site to have a really clean look. I wanted to make the choices on this page very clear, and to limit the amount of choices so students know exactly where to go. From the left-hand sidebar, I removed pages that my students wouldn’t ever need to access, like Piazza and Photo Roster.

Modular Course Design

In consultation with Columbia’s Center for Teaching & Learning, I implemented modular course design. What this means is that I didn’t publish all course content on Canvas right away; instead, I published modules gradually over the course of the semester. Although the course syllabus is available on Canvas in its traditional form, I released the modules themselves at particular pedagogical stages of development, allowing students to concentrate on a given module with me both synchronously and asynchronously.

Modular course design has a few benefits. Instructors of online courses have used modular format for quite some time, but if you’re newer to online teaching as I was, you might think that all of the modules should be released at once. Many online classes unlock modules in a progression, so that students access content in a carefully scaffolded system. So if you are used to teaching synchronously, I recommend that you unlock your modules in stages rather than all at once.

Think, for example, of those students you’ve probably had who want to read all of the novels ahead of time over the summer. They then don’t have any memory of those novels once it’s actually time to read them during the semester itself. The same thing applies to course design: being able to access all course content at once is overwhelming in terms of learning and process. Through modular design, you and your students progress together as a group.

You can also narrate the learning objectives for every unit. I wanted students to start thinking about content and skills together, and modular design made this more possible.

In terms of making the modules visible to students, I wanted everything to be accessible together. I wanted to think about the ways each student might be able to access the course, particularly given the specific challenges of this term. At the top of each module, students will see the different key terms I’m using. Early on especially, I would also include an instructional video designed for learners at various stages.

Finally, I think the most important element I included was a podcast of me reading text selections for my students. This was inspired by teacher and scholar Michael Wesch, who has a fantastic YouTube series on how to make teaching accessible. I’ve read to my 10-year-old son since he was born, and now my students listen to me reading to them while they’re on a walk or doing the dishes. (After reading my evaluations, I now know that many read the text on the page or screen as they listened to me).

Multimodal and Multimedia Theories

The modules, like other aspects of this course, were designed in terms of multimodal or multimedia approaches to learning theory and design. I’m using the term “multimodal” purposely in part because pedagogy scholarship has complicated the previous idea of different types of learner. What researchers have shown is that everyone is a different kind of multimodal learner. We learn and process in different ways in different contexts.

In this course, I really wanted to explore different methods and modalities of participation. One of the most recurring comments in my evaluations was that students love the opportunity to participate in lecture, but students who are more shy or are less familiar with English wanted other kinds of opportunities to participate.

One of my approaches was to use asynchronous discussion boards. Instead of Canvas discussion boards, I opted to use the program Padlet for our participation pages. It’s very easy to use Padlet to cut and paste HTML code into your course site. It will look to a student like a Pinterest board. Padlet is available for free, and there is a $10 membership for unlimited Padlets. I also want to note that the Padlets were ungraded and voluntary: this was an option for students. I wanted to be careful of the labor for both students and TAs.

My CTL consultant told me that students have said in the past that discussion boards are where ideas go to die! Mindful of that, I worked to integrate discussion posts into lecture as much as possible.

Chat for Student Engagement

Because I had over a hundred students in the class, the choreography of student participation was very difficult. Even if you raise your zoom hand, it’s hard for me to see students. And for security reasons, I also prevented un-muting during lecture. So chat was a great, multimodal way for students to participate.

I try to incorporate chat contributions into lecture in various ways. For example, occasionally I will stop and read the chat aloud, out of interest in maximum accessibility for students. I then collate their work by writing on a chart paper behind me – making this as big as possible – or using a lightboard setup that allows me to analyze a quote live with my students. I also like to use Google Jamboard, where students can add sticky notes and then move the notes around.

The chat is also a space where instructors or TAs can do some note-taking as well. My TA Irene Hsu had the brilliant idea of live-note taking during lecture, and students frequently mentioned this technique as one of our most effective instructional strategies. Zoom now offers a live transcript, but using the chat to take notes models effective note-taking for our students. It also helps our students who might be having internet connectivity issues, or who are English language learners, or need a back-up for whatever reason.

Multimedia Scaffolding for Writing

For this course, I wanted to think about how the work I did with writing could be illuminated in various ways for my students. To achieve this, I designed writing modules where I posted short instructional videos on different writing-related topics, such as introductions.

I also created videos for the different assignment sections of Canvas, walking my students through all elements of each assignment, from the prompt to the submission requirements. These videos don’t need to be high-end or elaborate; you can just record them on Zoom.

Finally, I gave students multimedia options for the assignments themselves. From the keywords quiz to the final paper, students could make recordings, they could create something visual, or they could do regular written work. For example, one of my students did a beautiful schematic keyword response using various stunning visual elements. They all did really fantastic things overall: video essays, an interactive museum, e-fiction using Twine, and a graphic fiction interpretation of a short story.

Q&A Discussion

How exactly do you handle the note-taking in chat during class?

DC (Denise Cruz): For note-taking, I’ve had four TAs this semester, and I had two of them per class working with the chat. I had the chat window open — I’m pretty comfortable with having the multiple windows. And I didn’t really give instructions; the TAs just came up with the idea! Sometimes I use the chat too: if I named a scholar or writer with an unfamiliar last name, I would stop and use the chat for that as well.

Who manages your Canvas site? You or your TAs? How did the CTL help?

DC: I manage the site myself. The CTL resources are helpful. It’s pretty easy to embed a video, for example. The one thing people should do is enable Panopto to embed video. When you’re in your Courseworks site, hit the “edit” button on a given page, and you’ll see a green “Panopto Video Recordings” icon in the toolbar.

How do you make and use a lightboard?

DC: My spouse and I built the lightboard, by constructing a frame around a piece of Plexiglass and putting LED lights around it. There’s a short YouTube tutorial for how to do this. You can set it up in about an hour.

I write on the board with neon markers. And I use a virtual camera that flips the image: because I’m writing on glass, everything is in reverse, so the flip ensures that students see the image the right way.

What adjustments have you made for students who are in different time zones?

DC: I record all class meetings. I used to think students would use recordings to not attend. But that’s not the case (and research supports this point), particularly if you make lectures something where students want to be there. This is why student collaboration and engagement really matter to me. My students are always curious about what I will do in class. My students, I now know from evaluations and comments, used the recordings at various moments in class, including to review material or so that they could listen first and take notes at a later point.

You should consider setting up an accountability process with asynchronous students. Using Panopto, you can track statistics, which I recommend. You can see who’s viewing, for example.

For larger lectures, I recommend that you look at these stats because it will help you catch students who need help or who might need resources. I would write to these students and say, “I notice you’ve neither attended lecture nor watched recordings. I’m writing primarily out of concern. Are you ok and do you need help?” I also asked students if they wanted me to set up an accountability email, and they found that very helpful.

Another plus of Panopto is you can also do captions, which students very much liked. Recordings are embedded in the modules, so they can find everything in one place.

Finally, to help students feel supported, I put them all in “success pods” (with thanks to Amanda Irwin for this idea). I placed everyone in groups of 4 at the outset of the semester. I explained to them that they now had 3 other people they each knew in our class; they could ask questions of each other, or do group projects together, or form study groups. Ultimately, they all want to feel like they can still make friends.

What is the longest text that you shared in the podcast format?

DC: The idea of the podcast was to get them started, so the most successful podcast reading I did was for a text that incorporated a lot of dialect and was just a little less familiar for the students. I just read the first two chapters of that for them; once they got comfortable, they switched to the regular text-based version.

For these recordings, I used my broken iPhone! You could potentially use voice memos. For the podcast, I used Garage Band. iMovie is also very popular. But you can do everything with your smart phone or even a laptop.

How would you adapt these approaches to a smaller course format?

DC: A lot of these strategies do work well for discussion-based courses. And I actually was regularly meeting with my students in small groups. I cut the lecture time to 45 minutes because I knew I was hitting everyone’s attention thresholds, and that gave me time to meet in smaller discussion groups for 25 minutes every two weeks.

With smaller groups, one thing that worked well was using the Jamboard. Most recently, we took the first 5 minutes of a discussion group meeting to do a synthesis activity where I picked a keyword for the class and students (about 25-30) crowd-sourced different keyword connections. Or, sometimes I give students the option to turn the camera off and write, in various forms.

I had heard from student surveys that, for lectures, it was hard to do breakout rooms. So the other thing that has worked for discussion groups is chart paper, or using a shared Google doc, or group-annotating a passage.

How do you structure your lectures? Do you break those 45 minutes into chunks?

DC: My lectures are argument-driven. I model the kinds of arguments I want them to do in their papers.

I do break them into chunks. There are usually two points in the lecture when I invite students to group-read something with me. Sometimes I’ll have free-writing — usually through the chat. I would watch and read the chat aloud, and sometimes we would have up to 60 contributions.

You can also use Poll Everywhere or the Zoom polling tool for in-class activities. For example, I might say, “What word do you notice?” Or, “Which character did you side with?” You can then share the poll results live, including by making a live word cloud. Students really like to see this.

Do you have tips for managing time and keeping these approaches sustainable?

DC: I’d recommend keeping it raw and letting go of perfection.

Tools & Resources

The Center for Teaching & Learning:

Platforms and Software:

Tech and Gadgets:

Diana is a PhD candidate in the Department of English & Comparative Literature. Her teaching and research interests include the Victorian novel, histories of science and medicine, studies of the environment, and theories of gender and sexuality. She has taught literature and writing classes at Columbia University, Barnard College, and Mills College, and she is currently a Senior Lead Teaching Fellow at Columbia's Center for Teaching & Learning.

One thought on “Practical Strategies for Multimodal Teaching”

Thank you for the in-depth analysis of multimodal learning. I found it very helpful.