Giant of Great Strength Mask : A Tentative Biography

by Victoria Jonathan

This Tibetan mask is kept in the reserves of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, New York City). There is very few information about it, which makes this biography highly hypothetical. This work hence leads us to discuss the possibility and relevance of such a project as an object (and particularly a mask) biography.

|

| Giant of Great Strength Mask, Tibet |

|

| Owl mask |

|

| White Spirit mask |

The Moravian mission in Ladakh in late 19th century

The only reliable information about this mask is that it has been acquired by the AMNH in 1920, and that it is part of a group of masks which share the same stylistic features and which were collected by missionary Dr. Karl Marx.

A research on Marx can help us speculate about the time when this mask was collected and the place where it was found. Dr. Marx was part of the Moravian mission in Tibet. He came to Leh (Ladakh) as a medical missionary in 1887, and participated in the creation of the mission’s first hospital there in 1888 {1}. Beside

|

| Fire Robber mask |

from his medical action, Marx seems to have had scientific interest in the culture of the region where he lived: he is the author of a History of Ladakh (“Three documents relating to the History of Ladakh” published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society

|

| Mask |

ofBengal, vol.LX, part I, Calcutta, 1891). He also partially translated the Book of the Kings of Ladakh {2}.

We can infer from Marx’s biography that the Giant of Great Strength mask was purchased by him

in Ladakh some time between 1886 and early 1900s. It was later acquired by the museum in 1920.

|

| Black Devil mask |

The mask is part of a group of nine masks kept at the AMNH. The eight other masks’ names are: owl mask, black devil mask, fire robber mask, white spirit mask, raven face mask, burning dorje mask, (blue) mask. How is this ensemble of masks coherent? Do these masks represent deities of a certain Tibetan pantheon? How do they interact together

|

| Raven Face mask |

?

Tibetan masks were mostly used in performances, masked dances such as Cham. But they could also serve as protective icons hung in an oratory. This ensemble of masks does not seem of very good quality compared to other Tibetan Buddhist

|

| Burning Dorje mask |

productions: their style is quite crude and rustic. Does that mean that they belonged to a small monastery that could not afford masks of better quality?

Physical description and possible meaning/affiliation of the mask

The Giant of Great Strength mask is made of clay and colored with black, red, light brown and white pigments. A cord is attached in the back. A blue silk cloth (probably from China) is attached to the mask by a thread. It is about 14 inches long, 10 inches wide, and 5 inches high, almost twice as big as a human face. The mask has a frightening aspect, produced by the combination of colors and the presence of scary elements such as skulls and flames. Its aspect comprises several elements of the Buddhist iconography.

The most used color is black (applied to the face, the pupils and around the white of the eyes). The red pigment enhances the face’s organs : eyes, mouth and tongue, nostrils, ears. This color also evokes blood. The light brown pigment is used to draw flames on eyebrows, cheeks, chin, lower and upper parts of the face (collar and crown). The white pigment is used on skulls, on the two pointing teeth and on the white of the eyes.

There are wrinkles on the nose, the cheeks and above the eyes and eyebrows, that could well be the expression of a face distorted by wrath. The eyes are set far apart, which enhances the frightening aspect of the mask.

|

| Mask, Tibet (papier mache) |

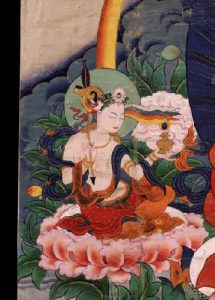

The mask has some characteristics typical of the Buddhist iconography of wrathful deities: its three eyes are topped by flames, the top of its head is surmounted by a crown of five skulls (in contrast with the crown of five leaves of the boddhisattvas) that recalls the destruction of the five passions, its open mouth shows bare fangs… Here is a picture of a Tibetan mask (from the collection of the Rubin Museum, New York City) of a different style, which still shares the same features, infering the Giant of Great Strength mask is part of a certain iconographic group of Tibetan masks.

These characteristics and the dark color of the mask recall the deity Mahakala (mGon po in Tibetan), a wrathful protective deity who was often the central deity represented in Cham rituals. But this mask could also well be a secondary deity assisting the principal deity in a ritual of Cham.

The function of the mask : an element of Cham ritual or a protective effigy?

The name Giant of Great Strength is mysterious, like the names of the other masks of the collection. It does not have any relevance in a Buddhist or Cham context. Maybe it was a character in a local myth or in a myth derived from the Bön religion, that was melted with Buddhist practice? However, the Giant of Great Strength mask could well be a transposition of Mahakala. Given the previous information, this mask could have been used in a Cham ritual, or as a protective effigy.

In Tibetan Civilization (1972), R.A. Stein defines the role of masks in Buddhism as a didactic one. Even though the ritual shall manifest the presence of deities through meditation, they remain invisible for laypeople. Masks are supposed to facilitate the manifestation of a deity. Their didactic role is notably displayed in masked dances (Cham). Mahakala is usually the principal deity in these danced masks. The Giant of Great Strength mask could have been used in Cham rituals. Therefore, does the mask represent a principal deity (like Mahakala) or an assisting deity ? How does it interact with the other masks of the collection in a Cham ritual ? Which monastery do they come from ? What type of Cham narrative were they used for ? These questions remain unanswered.

The Giant of Great Strength mask was possibly used in a Cham ritual. But Cham masks are usually made of wood or papier mâché (like the other mask from the Rubin Museum). This mask is on the contrary made of clay, and hence it seems too heavy to be worn by a monk dancer during a performance. The fact that the back of the mask has no holes for the eyes (but only a hole for the mouth) strengthens this idea, but it is reported that in some performances the dancers would hold the mask with two hands and look through the mouth. The Giant of Great Strength mask could otherwise have been a protective effigy, hung on the wall of a monastery or kept in a secret oratory (like a gonkhang) where deities reside – the blue silk cloth serving as a cover for the deity and its magic power. In Oracles and Deities of Tibet, René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz describes a gonkhang, “the holiest room of a temple” :

“The mgon khang is usually a dark room, lit only by a few butter-lamps burning in front of the images, which represent various chief dharmapalas and the particular guardian-deities of the monastery. Most of these images images are scarcely visible under the numerous ceremonial scarfs which have been draped over them. (…) The pillars of this chapel are decorated with masks, representing the angrily contorted faces of the various dharmapalas.” (p. 402).

The mask biography: a vain exercise?

Very few information could be gathered about this object. Is the Giant of Great Strength mask a derived form of Mahakala? Was it used during Cham dances? Or was it kept in a monastery as a protective effigy? The biography of the Giant of Great Strength mask mostly remains a mystery.

In The Way of the Masks (1979), Lévi-Strauss examines some masks from the Northwest Coast of Native North America. According to him, masks cannot be interpreted as separate objects. It is necessary to place them in their group of transformation to understand their signification. He proposes a methodology for the study of a group of masks which consists in the examination of their : aesthetic characteristics, technique of fabrication, use, benefits, related myths. There are three main dimensions of the mask : its plastic form, its semantic function (myth) and its ritual use. But this symbolic and imaginary ensemble remains subordinate to the social and economic infrastructures of a society. According to Lévi-Strauss’ structural perspective, the project of an object biography is nonsensical. A mask is not what it represents, but rather what it transforms, that is to say what it choses not to represent. A mask is the affirmation of a style, against the neighbor’s style. It is not possible to understand it independently of the other masks that it is not.

Thus, according to Lévi-Strauss, a mask cannot be studied as a sole object, it must be placed in the broader context of all the other masks that it does not represent. Still, if a “scientific” and exact approach of the Giant of Great Strength seems quite impossible, cannot we compare this mask with other relatively masks from the Himalayas and other parts of the world? Cannot we consider a relation between different masks other than semantic or ritual, like an aesthetic relation?

|

| Monkey Mask, Nepal, 19th-20th century |

Comparative perspective

The Giant of Great Strength mask can be replaced in the broader context of Himalayan masks. According to a few scholars (like Chazot or Murray), there are three main categories of Himalayan masks (but the frontiers between the three are quite porous):

– tribal masks or primitive-shamanic masks: they can represent the souls of ancestors, be used by shamans to practice divination and provoke a trance, or used as protective totems.

– village dance masks: they derive from local myths but often incorporate Hindu or Buddhist elements.

– monastery masks or classical masks: they are usually worn by Buddhists or Hindus in dance ceremonies.

Himalayan masks can be said to have a profoundly rooted international style: they resemble masks from other parts of the world, like Japan, Northwestern Native America, or Africa. There is a universality of the culture of masquerade.

Here is another mask from the Himalayan region. It is a tribal Monkey mask, made of wood and polychrome, probably from the turn of the 20th century. It is exhibited at the Rubin Museum of Art (New York City). This mask is from the Terai region, in southern Nepal, near the Indian border. It represents a monkey in a minimal style. The multi-layered pigments and the crack on its right side suggest that it has been often used and repaired. The Tharupeople from Terai have preserved a form of animism and shamanism. They use masks in theater performances that mix their local beliefs with cultural epics (like the Ramayana, in which monkeys have a special role).

|

| Fang Mask, Gabon, 19th century |

With its long face and very simple style, this Himalayan mask looks like an African mask, such as this Fang mask from the collection of the Musée du Quai Branly (Paris). Maybe, ultimately, the universality of masquerade invites us to a comparative perspective that in turn tells us more about us than we can tell about the masks. This is what Madanjeet Singh suggests in Himalayan Art(quoted from Murray’s article): « … these ageless images are undoubtedly the most fantastic and formidable art-link in the entire Himalaya. With these masks, we are presented with a radical departure from cultures and aesthetic more familiar to us. They provoke us emotionally and intellectually. And their examination offers both an occasion to develop intuitions about peoples, far distant and long ago, as well as insights about one’s self, here and now. »

|

| Modigliani, Head, 1911 |

At the beginning of the 20th century, Western artists were quite fascinated with masks, and the ‘primitive’ culture of masquerade can be said to have had a great impact on the experiments of Modern Art. In pre-World War I Paris, Montparnasse artists were very influenced by their visits to the Musée de l’Homme, Paris’ equivalent of New York’s AMNH. African and Cambodian art inspired Modigliani’s sculptures.

African tribal masks were also very influential in Cubist experiments, which is obvious in some of Picasso’s works like Les demoiselles d’Avignon (MoMa, New York City). In The Story of Art, Gombrich evokes the role of tribal masks in Modern Art, as “a way out of the impasse of Western art” and a “search for expressiveness, structure and simplicity” (p. 563). In a paragraph about Picasso and Cubism, he writes : “{Picasso} began to study primitive art, to which Gauguin and perhaps also Matisse had drawn attention. We can imagine what he learned from these works: he learned how it is possible to build up an image of a face or an object out of a few very simple elements.” (p.573).

|

| Picasso, Les demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 |

|

| Man Ray, Noire et blanche (Black and White), 1926 |

Another example of the fascination of Modern Art with primitive art can be found in this photograph by Man Ray. The photographer pairs the face of his model Kiki of Montparnasse with an African mask, creating a surprising and beautiful contrast between black and white, primitive and modern, representation and reality.

Notes

{1} “In April 1887 Dr. Karl Marx arrived in Leh to take over the hospital and clinic which were partly sponsored by the British Government. Dr. Karl Marx was the first trained missionary doctor to be sent to Ladakh.” in Tourism in Ladakh Himalaya, Prem Singh Jina, Indus Publishing, 1994 (p. 42).

{2} “Dr. Karl Marx (…) was able to acquire further, more detailed manuscripts of the Ladakh Chronicle {from the former King of Ladakh}. He found Schlagintweit’s version very unreliable when he compared it with the other texts, and begin work on an improved translation. Unfortunately he died when only a thord of his work had been printed. His manuscripts and the drafts of his translations of the second and third parts were sent to his brother in Germany.” in Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5, Henry Osmaston and Philip Denwood, Motilal Banarsidass, 1995 (p. 398).

References

Bird Isabella, Among the Tibetans, Oxford, 1894.

Chazot Eric, “The Masks of the Himalayas”, Orientations, October 1988.

Gombrich Ernst, The Story of Art, Phaidon,1995 (1950).

Lévi-Strauss Claude, La voie des masques, Plon, Paris, 1979.

Murray Thomas, “Demons and Deities – Masks of the Himalayas”, HALI n°2, 1995.

De Nebesky-Wojkowitz René, Oracles and Demons of Tibet – The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities, ‘s Gravenhage, Mouton, 1956.

Stein R.A., La civilisation tibétaine, Paris, Dunod, 1962.

Special thanks to Isabelle Charleux, Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy and François Pannier for their insightful help.

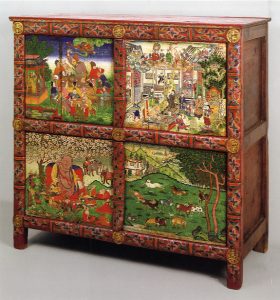

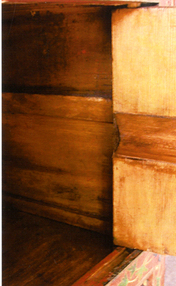

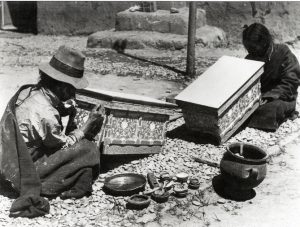

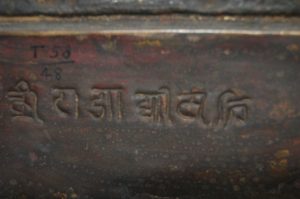

Wood for construction purposes was available in the highlands of the central Tibetan plateau (where the largest urban hubs, Lhasa and Shigatse, are located), but this was a local softwood referred to as chapa; it was the timber of the spruce, pine and fir trees found in the forests of the eastern province of Kham that was prized by furniture makers. [6] Most likely constructed from one of these quality hardwoods, the Newark chagam displays the frame-and-panel style typical of Tibetan cabinets: doors and – sometimes – sides are composed of discrete panels set into an enframing structure, creating a visual effect not unlike that of a coffered surface. Here, each of the four doors is hinged with wooden dowels, or connective pegs (above), which attach the top and bottom of the door to its frame, allowing it to swing open and shut. The doors were originally fastened around the central decorative brass loop by a metal plate (of the sort seen at right) and a lock, both now presumably lost. [7]

Wood for construction purposes was available in the highlands of the central Tibetan plateau (where the largest urban hubs, Lhasa and Shigatse, are located), but this was a local softwood referred to as chapa; it was the timber of the spruce, pine and fir trees found in the forests of the eastern province of Kham that was prized by furniture makers. [6] Most likely constructed from one of these quality hardwoods, the Newark chagam displays the frame-and-panel style typical of Tibetan cabinets: doors and – sometimes – sides are composed of discrete panels set into an enframing structure, creating a visual effect not unlike that of a coffered surface. Here, each of the four doors is hinged with wooden dowels, or connective pegs (above), which attach the top and bottom of the door to its frame, allowing it to swing open and shut. The doors were originally fastened around the central decorative brass loop by a metal plate (of the sort seen at right) and a lock, both now presumably lost. [7]

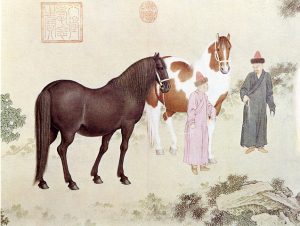

The scenes, beginning clockwise from the upper left, have been identified as: Central Asians and Qing officials gambling and eating in the garden of a Lhasa nobleman (left); a Chinese gentleman hosting a party at which a magician is conjuring up coins and celestial beings; the Chinese patron and sage Hva-shang; and, lastly, frolicking horses in a Tibetan landscape. [17] The first of these is notable chiefly for the racialization of its figures: Central Asia, the region once known as Turkestan and today the Chinese province of

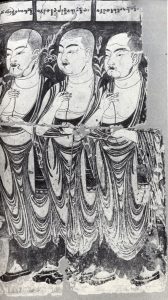

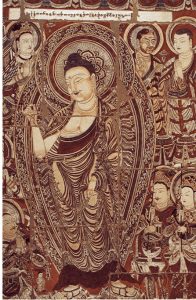

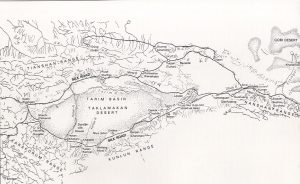

The scenes, beginning clockwise from the upper left, have been identified as: Central Asians and Qing officials gambling and eating in the garden of a Lhasa nobleman (left); a Chinese gentleman hosting a party at which a magician is conjuring up coins and celestial beings; the Chinese patron and sage Hva-shang; and, lastly, frolicking horses in a Tibetan landscape. [17] The first of these is notable chiefly for the racialization of its figures: Central Asia, the region once known as Turkestan and today the Chinese province of  Continuing their advance along the corridor they next brought to light from beneath the sand fifteen giant-sized paintings of Buddhas of different periods. Other figures, shown kneeling before the Buddhas offering gifts [right], were of particular interest to von Le Coq since they depicted individuals of different nationalities. They included Indian princes, Brahmins, Persians – and one puzzling character with red hair, blue eyes and distinctly European features. [22]

Continuing their advance along the corridor they next brought to light from beneath the sand fifteen giant-sized paintings of Buddhas of different periods. Other figures, shown kneeling before the Buddhas offering gifts [right], were of particular interest to von Le Coq since they depicted individuals of different nationalities. They included Indian princes, Brahmins, Persians – and one puzzling character with red hair, blue eyes and distinctly European features. [22]

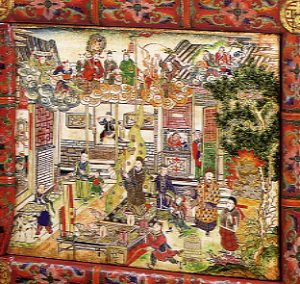

The second panel (left) marks a departure from its brethren: its subject matter and style suggest that the artist was looking directly to Chinese woodblock prints for inspiration, and may indeed have been a replacement for an original door. [28] Similar scenes can be found in that genre commonly referred to as New Year pictures, or nian hua (年画), the earliest examples of which may be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (841 – 256 BCE), when designs of animals like tigers were pasted onto the gates of domiciles as apotropaic talismans during the Lunar New Year. Two manuals attributed to the Song Dynasty statesman, scientist and polymath

The second panel (left) marks a departure from its brethren: its subject matter and style suggest that the artist was looking directly to Chinese woodblock prints for inspiration, and may indeed have been a replacement for an original door. [28] Similar scenes can be found in that genre commonly referred to as New Year pictures, or nian hua (年画), the earliest examples of which may be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (841 – 256 BCE), when designs of animals like tigers were pasted onto the gates of domiciles as apotropaic talismans during the Lunar New Year. Two manuals attributed to the Song Dynasty statesman, scientist and polymath

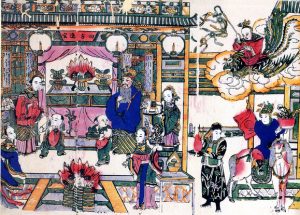

The bottom pair of panels likewise present interesting studies. The one on the left portrays Hva Shang – whose name is a transliteration of the Chinese term for a monk, he-shang (和尚) – considered the Chinese patron of the 16 Arhats. Historical accounts tell us that he was sent by Tang emperor to extend an invitation to the Buddha Shakyamuni, but, the latter having already passed on, addressed himself to the arhats instead. Hva Shang is usually portrayed as a bald, portly figure, seated beneath or beside a flowering tree with a rosary in his right hand and an offering to the arhats in the left, and frequently surrounded by cavorting children and one or more Buddhist deities. [31]

The bottom pair of panels likewise present interesting studies. The one on the left portrays Hva Shang – whose name is a transliteration of the Chinese term for a monk, he-shang (和尚) – considered the Chinese patron of the 16 Arhats. Historical accounts tell us that he was sent by Tang emperor to extend an invitation to the Buddha Shakyamuni, but, the latter having already passed on, addressed himself to the arhats instead. Hva Shang is usually portrayed as a bald, portly figure, seated beneath or beside a flowering tree with a rosary in his right hand and an offering to the arhats in the left, and frequently surrounded by cavorting children and one or more Buddhist deities. [31]

by Hojeong Choe

by Hojeong Choe

The pattern of leaves which seem like sal tree leaves shows that artisan of the object knew and expressed the element of

The pattern of leaves which seem like sal tree leaves shows that artisan of the object knew and expressed the element of