Cloth

|

| Boots |

Cloth boots are made of thick cloth or canvas and they are soft, flexible and lightweight.

Resources for Tibetan History Scholarship

|

| Boots |

Cloth boots are made of thick cloth or canvas and they are soft, flexible and lightweight.

History

Cloth Canvas Corduroy Velvet Leather Felt Silk Cotton

Function & Purpose: What were each of these textiles mainly used to make in Tibet? Given the unique characteristics of each type of textile: Do the properties of a textile make it particularly suited for use in making a certain item? Do practical concerns for the function of an item outweigh the traditional craft and construction of the item? What purpose did the items made from each particular textiles serve? How have the function and purpose of these items changed and/or evolved over the years, within the context of Tibetan tradition and culture?

Form & Style

Given the effect that the type of textile used has on the form and appearance of an item: Were certain textiles reserved for making traditional, seasonal or ceremonial items? Which textiles were used for: traditional, seasonal items and ceremonial items? How has the form and style of these items changed over the years? How similar or different is the style of Tibetan clothing when compared to inhabitants of the surrounding areas?

*This project is currently under construction, though the finished product should roughly follow this outline. The goal of this project is to unite the research from two separate object biographies under the general category of textiles . The object biographies were written on a pair of Boots and a Tibetan Silk Dancing Dress, which are both in storage at the American Museum of Natural History. My hope is that by providing general, easily accessible information about various textiles (that continue to be used in the production of materials in Southeast Asia) to other students (especially those undergraduate students who are new to the field), that they will be more informed and more curious to research and explore other material objects. As the research continues, perhaps we can further relate the rich culture of Tibet to contemporary clothing and traditional costumes.

Classification of Materials:

Weaves:

Symbols:

An American diplomat, W.W. Rockhill, who was influential in thought and action to the Far East once said, the natural conditions have exercised a marked influence on the degree of culture of Tibet and must not be lost sight of in any study of the inhabitants. Rockhill’s idea is vitally important in researching discussing traditional Tibetan clothing or outerwear, such as boots and dresses.

Related pages:

[1] Notes on the Ethnology of Tibet by W.W. Rockhill P. 673

by Victoria Jonathan

Jacques Marchais (1887-1948) was a woman

Jacques Marchais (1887-1948) was a woman

who had an early interest in Tibetan culture and who built a museum on Staten Island that she thought of as an educational center to provide American people with a place of encounter with the East. This article relates the biography of both Jacques Marchais and the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art , which raises a few questions about museums in general.

who had an early interest in Tibetan culture and who built a museum on Staten Island that she thought of as an educational center to provide American people with a place of encounter with the East. This article relates the biography of both Jacques Marchais and the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art , which raises a few questions about museums in general.

The information provided in this article comes from different sources: an exhibition held at the Jacques Marchais Museum, press releases from her gallery and museum, correspondance, autobiographical notes, newspapers, and articles by the most recent curators of the museum.

She was born Jacques Marchais Coblentz in 1887 in Cincinnati (Ohio). Her father died when she was little and her mother sporadically took care of her; she went to different orphanages and homes during her childhood.

She started at age 3 in Chicago a career as a child actress, known as Edna Coblentz or Edna Norman (her mother’s family name), both names her mother thought more appropriate for a stage career. Her mother put her on the stage because of financial issues. She performed in quite notable plays at the time (like A White Lie and Silver Shell at Hooley’s Theater, and A Modern Match at the Shiller Theater). She was also invited to wealthy families’ houses in Chicago to perform recitals (among them, the crime boss Mike McDonald), families who paid for her education.

At the age of 16, she traveled to Boston in a comic play by George Ade (one of the most popular writers in America during late 19th-early 20th century), Peggy from Paris, where she met her first husband, Brookings Montgomery, a wealthy MIT student. Their marriage was reported as scandalous in the newspapers and Brookings’ family disinherited him. The couple had three children: Edna May, Brookings Jr. and Jane, and later went to live with Edna’s husband’s family in Illinois because of their financial problems. They divorced in 1910.

Edna was later briefly married to a hotel manager, Percy S. Deponai, and divorced in 1916-1917.

Some questions are raised about Jacques Marchais’ name. How come she had a French male name and changed it a few times in her life? She reported that her father (John Coblentz) chose this name before her birth and kept it even though she was a girl. Her mother renamed her for her stage career as a child. She later took up her supposedly birth name until her death, a name she used in her career as a collector. {1}

In a context of war and crisis of Western civilization, many American intellectuals grew an interest with Eastern culture and theosophy. When Jacques Marchais moved to New York in 1916 in order to pursue her acting career, she took part in a social circle of artists, travelers, scholars, scientists and aristocrats who were all curious about Asian spirituality and Buddhism. Jacques Marchais can be thus said to one of the first active participants in the beginning history of American Buddhism.

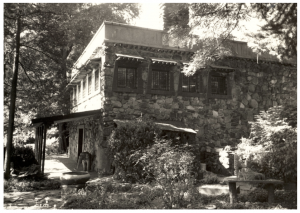

In about 1920, she married a businessman from Brooklyn, Harry Klauber (1885-1948), the owner of a chemical factory. They moved to Staten Island in 1921 with her children. At the time, Staten Island was the countryside. They built a house there, which they thought of as a haven of peace where to welcome their friends.

Among their friends:

➢ Claude Bragdon (1866-1946) was an American architect who moved to NYC in 1923 and worked in the theater world. He was interested in yoga, theosophy and Buddhism. He wrote books like Old Lamps for New : Ancient Wisdom in the Modern World (1925), An Introduction to Yoga (1933), More Lives than One (1938). {2}

➢ Syud Hossain (d. 1949) was a friend of Gandhi who was active in the Indian Independence Movement. He exiled himself to the United States to find support for Indian independence, giving lectures and writing articles and books. In 1933, Jacques Marchais helped him organize the “Roundtable of Contemporary Religion” in New York.

➢ Ruth St. Denis (1879-1968) was an American dancer who founded the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in 1915 with her husband Ted Shawn in Los Angeles. First a vaudeville dancer, she created her own style of dance based on her interest in Indian philosophy and ancient cultures. She was the teacher of Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Louise Brooks. She had a great influence on modern dance.

An article published in 1937 in a Staten Island newspaper reports on a talk that Bragdon gave at the Klaubers’ house :

“the essayist and theatrical designer said civilization is now in masculine form – full of hatred and war. (…) ‘What we should strive for’, he said, ‘is a unity of being. The East has a technique for attaining this unity. It is called Yoga, which means many things; but fundamentally it means to recapture one’s birthright. Individualism has never been separated from the universal spirit. Yoga is a system that involves emotions and self-obligations.’ (…) The living room of the Klauber home provided an excellent setting for Mr. Bragdon’s talk. Oriental lamps, statuettes, vases and tapestries fill every nook and cranny. The persons who attended were all interested in thet East – its religions, its civilization and its philosophy.”

Why would an American actress born in Ohio have such a deep interest in Tibetan culture, in a time when very few people in the Western world had such interests?

In her own words, the genesis of this passion for Tibet was to be found in childhood memories, and particularly in a trunk that contained thirteen Tibetan bronze figurines that once belonged to her great grandfather, John Joseph Norman, a merchant from Philadelphia active in the tea trade. {3}

In her article about Jacques Marchais, Barbara Lipton reports that “the records show that at least ten of the figurines were purchased in 1935” (Lipton, 10). So, is this story the beginning of it all or a lie? Anyway, this story was highlighted in her public relations exercise. In a press release entitled “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception” that documents the opening of the gallery, Jacques Marchais uses this story to explain her drive to build such a collection:

“When Jacques Marchais was between four and five years old, her mother opened a chest which had been stored in the attic of their home for many years. This chest had been unlocked only once during her mother’s childhood. It contained no family of old-fashioned dolls, such as might delight the heart of any little girl, but a collection of Ponist [Bon po] figures, brought from India by her great grandfather, Sir John Norman. He had become acquainted with several Lamas around Darjeeling, and one, who grew to be a particular friend, gave him this collection of thirteen Ponist figures, to which Jacques Marchais later added one, making fourteen in all of that particular type of figure. These original thirteen gods with which she played, while her childhood contemporaries mothered dolls, was the nucleus of the present-day and ever-growing Jacques Marchais collection.” An article published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on February 23, 1946, entitled “She Played with Statues Instead of Dolls – And the Little Girl from Ohio Came to Have the Richest Collection of Tibetan Art in the Western World”, relays this story.

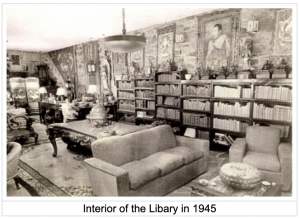

Because of her health issues and the political context, and to her regret, Jacques Marchais never traveled to Tibet. Her knowledge about Tibet was acquired from books. Her transplantation of Tibet to Staten Island is thus quite an imaginary one. But she was very well-versed. Her library’s collection included all the literature about Asia available at the time in English, and many of her books are annotated by her.

Jacques Marchais began collecting Indian and Tibetan art in the late 1920s. By the 1930s, she had become a renowned collector and notable person in the field of Tibetology. She began to imagine a place to house her collection, an educational center that would be an encompassing experience for visitors and where she could share her interest.

|

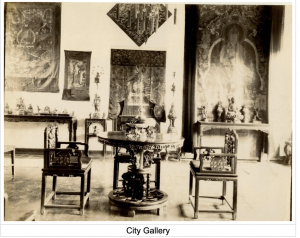

| City Gallery |

In 1938, she opened an Indian and Tibetan art gallery in the elegant neighborhood of Park Avenue (on 40 East 51st St, the building no longer exists and has been replaced by a skyscraper). For her, the gallery was a way to finance her project for a Center devoted to Himalayan culture: “The gallery is only a stepping stone toward doing something I think will be a help to humanity in the long run.” (Letter to Kate Crane-Gartz, January 6, 1940) She also said : “I only started this gallery as a fore-runner for the miniature copy of the Potala of Lhasa, which I hope to build on our hill adjoining the gardens, within the next five years. I hope to build it large enough to house 300 people at a time. It will be, of course, of fieldstone – the interior done in the color conducive to peace and meditation – with a huge Buddha smiling down upon them in a benevolent benediction.” (Letter to Claude Bragdon, February 6, 1940).

|

| City Gallery |

A press release entitled “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception” documents the opening of the gallery. It presents it as a haven of peace and spirituality: “There one may truly step into another world – a world whose people have not known war for many years, and whose spiritual side is magnificently represented by the various gods and goddesses (see Lha-mo for one) of the Tibetan pantheon, thang-kas (paintings), ritual implements and costumes used in connection with religious rites. Here visitors are always welcome.”

The gallery, which remained open for 10 years, provided her with funds for the building of the museum.

The museum

When Jacques Marchais and her husband Harry Klauber moved to Staten Island in 1921, he supported Jacques’ idea of building next to their house a Center devoted to Tibetan art and culture, consisting of terraced gardens, a library, and a museum. {4}

She started the Center by designing a garden that she named « Samadhi », a Sanskrit word for « establish, make firm » and a Buddhist term for describing a high level of meditation.

The library was then built, between 1943 and 1945. It was meant as a non-profit place for research for members only. It was comprised of about 2000 volumes of “books on occult subjects, Asiatic Art, Comparative Religions, Symbolism, Color, etc.” (Library press release). Jacques Marchais had built a comprehensive collection of the literature available in English on these subjects at the time.

In a press release, Jacques Marchais announced the opening of the Library on July 29, 1945, and defined the terms of her Library. {5}

|

| Interior of the Libary in 1945 |

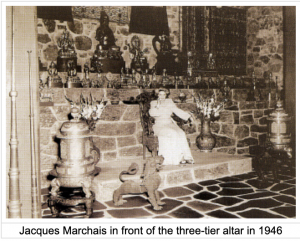

She later built the museum to house her collection of Himalayan art. She called the museum the “Temple Room” or the “Chanting Hall”, and wanted it to look like a Himalayan temple. Her influence for the architecture of the museum were the Potala of Lhasa and a pavilion called “Chinese Lama Temple: Potala of Jehol” she had seen at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. {6}

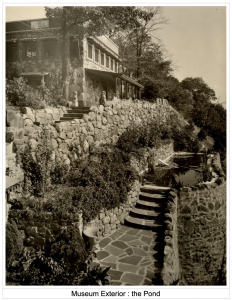

She was inspired by pictures from her books, and included such details as the long flight of stone stairs leading to the Center, a pond, meditation cells, trapezoidal windows, pagoda shaped roof. She was personally involved in the construction of the center. She designed the whole project (she even made prayer-wheels herself), and entrusted Italian immigrants with the task of building it. She conceived of a Tibetan Buddhist three-tiered altar made of mica for the room. The objects displayed on the altar are of sacred and spiritual meaning.

.

|

| Jacques Marchais in front of the three-tier altar in 1946 |

She expressed her refusal to hire architects in a kind of “feminist” stance: “Each stone was lovingly picked by me and hauled that has gone onto its walls. And I was successful in getting it up without benefit of one architect, contractor or purchaser of the materials. I was able to prove to myself that one woman could do it if the talent was great enough and the urge and willingness to work hard was strong enough.” (July 27, 1945, on building the Library) {7}

She envisioned her Center very precisely, as she explained it to a friend: “The seven terraced gardens are completed but we are now engaged in blasting out rock in the side of the hill for the future potala. The building will face the southeast; and it is situated on the side of a hill (the highest hill from Maine to the Florida Keys) on the Atlantic Coast – but within 65 minutes of 51st Street. There will be ‘The Chanting Hall’, which will hold about 300 people on the top terrace – an Asiatic library, museum and my office on the second terrace – and on the third – will be storage rooms, bams for a few goats, etc. – and a large space in front of these buildings which will be flagged. Here we can give the cham (traditional sacred dances) and observers can look down from the upper terraces at the spectacle below. I have the gorgeous Tibetan costumes and masks that are worn in these dances.”

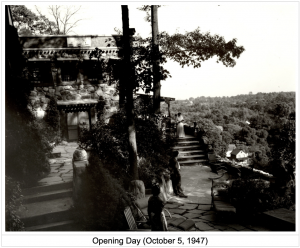

Jacques Marchais and her husband broke ground for the museum in 1941, and the construction went on from 1942 to 1947 (except in 1943 when it was interrupted because materials were scarce in a time of war). Jacques Marchais maintained her gallery during the construction.

When the Center opened in 1947, it was widely released in the national press (articles in the New York Herlad Tribune, Life, Buffalo Courier Express…). An article in Life Magazine (December 8, 1947 : « New York Lamasery : A New Tibetan Temple Bewilders Staten Island ») said: « Now the structure will be opened for ‘meditation’ to devotees of Tibetan culture like Madame Marchais, whose only regret is that she never has been to Tibet. »

|

| Opening Day (October 5, 1947) |

Jacques Marchais was greatly involved in this museum project:”My all has been given to this venture – my strength, my health, what little money I had, the collection and the building of the Library and Museum. There has not been one bit of outside help! I have not needed it. No reward is expected, other than the realization of my one ambition – which has been to house in permanent buildings my books and a replica, as near as possible, of a Tibetan ‘Chanting Hall’ with its golden altars, deities, religious implements, etc. For it is to prove to be a cultural benefit to those persons of the Western World who are seeking a better understanding of their Oriental brothers – their art, their religion and their philosophy.” (November 30, 1944)

But unfortunately, she died on Februray 15, 1948, four months after the Museum opened, and her husband died seven months after her.

In 1947, Jacques Marchais’ collections included 3000 valuable pieces of Tibetan art (thangkas, ritual implements, textiles, altar sets, furniture, jewelry, wood-blocks, and 1500 bronze deities).

After both Jacques Marchais and Harry Klauber’s death, the museum was managed by Helen A. Watkins, a friend and neighbor, and a board of trustees was formed. From 1953, she opened the museum to the public on an irregular basis. In 1959, the museum offered a refuge on Staten Island to the Dalai Lama, as it is reported in an article of the New York Times from April 4, 1959 (“Tibetan Sanctuary on Staten Island Contains a Spiritual Quality – Dalai Lama Gets Invitation Here”). She did what she could to maintain the museum, but it soon began to deteriorate, and hundreds of objects from the collection were sold off or stolen. Many objects from the Jacques Marchais’ collections were thus scattered in other Himalayan art collections; as a result, some of these objects are now part of other museums’ collections in United States (for instance, the two lions’ statues that appear in some pictures of Jacques Marchais’ gallery and museum belong now to the Asia Society, and have even become the Asia Society’s logo). Before her death in 1971, Watkins sold the house and terraced gardens next to the museum that had been the Klauber’s home.

From 1971, the museum was run by volunteers and a small board of trustees. It was open very irregularly. In the mid-1970s, the museum was taken care of for the first time by paid conservator and curator, benefiting from State financial help.

In 1985, Barbara Lipton became director and curator of the museum. Under her direction, a catalogue of the museum was published in 1996, including participation of renowned Tibetan scholars such as Donald S. Lopez. More than 200 objects have been added to the collections during this period. In 1991, the 14th Dalai Lama came to the museum and blessed the museum’s altar and collections. It is also during this period that the Center became known as the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art.

Since 2004, director Meg Ventrudo and curator Sarah Johnson have begun taking care of the museum collections: building renovation, proper storage and conservation of the collections, inventory… These basic operations have not have been completed since the museum’s opening because of management and financial issues. Few archival records exist of the the provenance of the museum’s collections, which make them difficult to trace.

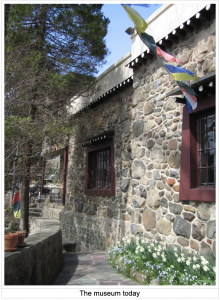

| The museum today |

Today, the collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art include about 1200 pieces of Himalayan art. Only 1000 objects remain from her original collection of 3000.

In building her Center, Jacques Marchais’ goal was to educate American people about Tibet: “The purpose of our corporation is… to make the American public more conscious of things Tibetan from an educational point of view.” (Letter to the Department of Licenses, July 2, 1940). She saw herself as an “instrument” in the diffusion of Himalayan culture: “Please do not think that I am an egotist, for no one knows better than I that I am but an instrumentused to preserve the art of an ancient people and to present it to a younger generation.” (Letter to Dr. Hans von Koerber, Professor, University of Southern California, December 11, 1944) In a time of Depression and World War, her aim was to bring a little bit of peace and spirituality to Western civilization. She felt she was charged with a mission that would benefit the entire world: “I have every hope that what I am doing, and the thought that is behind the scene of this particular endeavor, will prove a source of comfort to thousands.”

Ultimately, one could wonder what was her relationship with Buddhism. Was Jacques Marchais herself a Buddhist? In her time, Buddhism (known as Lamaism) was not well respected, and very little information about it was available in America (no Tibetans in the West, few translations).The vague idea people had about it came from the popularization of the “Shangri-la” through 1933’s novel Lost Horizon by British writer James Hilton – which described a utopian place of great harmony and a lamasery in the Kunlun mountains.

Jacques Marchais strongly identified with Tibetan culture and Buddhism, but never publicly claimed herself as a Buddhist. Rather, she showed an openness to all religions. Although she wanted her Center to resemble a temple, she did not conceive it as a place to convert people and proselytize, but rather as a place to educate them about Himalayan culture and spirituality. Her goal seems to have been more of a contribution to the mutual understanding of Western and Eastern cultures, and to religious tolerance. Nevertheless, she did express her belief in such concepts as karma and reincarnation among her circle of friends. {8}

How was the collection acquired? Jacques Marchais purchased items from dealers, auctions, and private individuals. She benefited from a period a chaos in Tibet and China. It was during this period, from 1911 to 1949, that Himalayan art was on the market for the first time, and that many collections were built in the West (for instance, the collections at the American Museum of Natural History, at the Newark Museum, and at the Philadelphia Museum).

In building her Center, Jacques Marchais had a wholistic approach of collections and context, spirituality and setting. Although she had never traveled to Tibet, she was extremely attentive to details and sought for authenticity.

In Sarah Johnson’s words, “Part of Jacques Marchais’ uniqueness as an institutional architect was her creation of a contextual setting that was conducive to the aesthetic appreciation of the artefacts. Affectionately terming her center a ‘miniature Potala’ or the ‘Potala of the West’ after the Potala palace, the historic home of the Dalai Lamas, in Tibet’s capital city, Lhasa, she wanted to evoke the architectural style of a Himalayan mountain monastery. The rustic fieldstone buildings themselves, as well as the objects contained in them, became tools for studying Himalayan identity. The environment of her centre’s location, with terraced gardens and a fishpond flowering with lotus, added to an atmosphere of serenity and beauty – an overall viewing experience that distinguished the institution from other art museums.” (Article in Asian Art)

Jacques Marchais’s project of a Museum of Tibetan Art, conceived as a “total” experience, raises some questions about museums and the way they display objects from different cultures. Is a contextualization of these objects necessary in order for the viewer to apprehend them? What is the role of architecture in museums? To what extent should the culture from which the objects come be represented?

Ultimately, Jacques Marchais can be considered a pioneer from different points of view. As a woman born at the end of the 19th century, she managed to live her own life and realize by herself a dream which was very singular at the time, to say the least. Her curiosity and imagination, as well as her drive to study with rigor, make her one of the first publicists of Tibet and Buddhism in the Western world. Given the popularity of Buddhism in America today, and of humanistic ideals of intercultural dialogue after World War II, Jacques Marchais can be said to have been a visionary.

|

| Museum Exterior : the Pond |

{1} “Edna was a stage name given me by my mother when she put me on the stage as a little child, and the name she usually called me – but, my baptismal name was Jacques Marchais Coblentz, which my father asked her to name me. The Jacques was his father’s name, and the Marchais was his mother’s maiden name. Her father was a sculptor. After I left the children’s father, I resumed my own name, which I had not used since Mother put me on the stage, at three and a half years of age. After my father’s death, that was. I have not used the name Edna since.“ (Jacques Marchais, Letter to Kate Crane-Gartz, December 3, 1945)

{2} Biography on http://www.lib.rochester.edu/index.cfm?PAGE=3514

{3} “One day my mother unpacked an old trunk that she had been keeping in storage (my curiosity was aroused and soon there began to appear from their shrouds of wrapping paper figurines most foreign to anything we Westerns are familiar with. Though I have never had any use or would not play with dolls I immediately took to these bronze figures. From then on they were my companions by day and my bedfellows by night. My mother never knew what they were except that they were brought to this country by her grandfather from Darjeeling. And it was not until I began to study and delve that I realized they belonged to the old Pon religion of Tibet. These figures were returned to their wrappings and relegated to the old trunk and placed in storage again, after I had outgrown my maternal instincts.

I never again thought of them until my mother’s death {1927}. Her belongings and the large old-fashioned trunk was sent to me. Upon going through her things I came upon the old loves of long ago and with a renewed and much more vital interest in them. I started to try to identify them.

I had been interested in India, her religion, her gods, etc. for some time. But nowhere in her old books were deities such as these. Only by accident had I come upon notes of mother’s grandfather on its old Shamanistic and Animistic Pon religion. Then the hunting began in earnest.” (cited in the current exhibition at the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art)

{4} In the library press release, Jacques Marchais describes her husband as “a ‘Rock of Gibraltar’ for her to lean on”, “giving her the necessary encouragement when things looked darkest and most discouraging for her and her work.”

{5} About the audience, she wrote: “This Tibetan Library will not be open to the public, but will be available to a selected membership of five hundred individuals only, who feel the literature to be found within its walls – in book and manuscript form – worthy their support. (…) These restrictions have been made to assure perfect peace and quiet to the members – and the exclusion of the merely curious and non-studious. The membership fees are to be used for the purchase of Tibetan manuscripts, books relating to Tibet – its life, politics, art, religion, etc., whenever available, and for the repair of bindings and the salary of a librarian-secretary.” About the nature of this institution (Library and future Museum), she said: “This project is strictly, in every sense of the word, a non-profit, non-sectarian organization. It is the only thing of its kind ever to be attempted outside of Tibet.”

{6} In a document entitled “Aims and ambitions of Jacques Marchais”, she explains her museum project in these terms:

“she is holding a museum to house the permanent Jacques Marchais Collection of Tibetan Ritual Art. This museum, which will have a large library for research and reference attached, is to be a miniature duplicate of the Potala in the forbidden city of Lhasa. It will be richly furnished and will have all those architectural details (in true Tibetan style) which make the difference (…).

For Madame Marchais, crusader in this field, has plans to endow her museum so that posterity may reap the benefits of her long and happy years of work. It is almost entirely due to her efforts that the true worth of Tibetan objects has become known in this country and their value as art recognized. »

{7} She also expressed: “I had to turn over my drawings – list of materials, etc. to ask an architect and from these drawings of mine he made the blue prints and filed the plans. (…) I was a lone wolf from the beginning to the end. When I found I had to have a requested archiect file my plans, I took three different men who did not know each other – gave them photos, my drawings and data – and told them to make the blue prints – I had a reason for doing this as you shall see. When they brought me the blue prints – they were alike of course. but each man had his name on the drawings, ignoring me entirely as the real architect. (…) It was because I knew what I was striving for – because I knew Tibetan architecture, symbolism etc. and was working for perfection that I insisted upon going it alone. You don’t have to be a registered architect to build beautiful buildings, but you do have to have a talent for design, authenticity etc. to do a good job. So, take heart you ladies who follow me. Express our ideas and don’t be afraid to carry them out. Only – don’t copy others. Be your own self – and good luck to you.” (J. Marchais, “The true story of the building of and designing of The Jacques Marchais Center of Tibetan Arts”, 1947).

{8} Her syncretic beliefs can be felt in a Poem she wrote on her 1944 Christmas card:

“Ad Coelum

At the Muezzin’s call for prayer,

The kneeling faithful thronged the square,

And on Pushkara’s lofty height

The dark priest chanted Brahma’s might.

Amid the monastery’s weeds

An old Franciscan told his beads;

While to the synagogue there came

A Jew to praise Jehovah’s name.

The One Great God looked down and smiled

And counted each His loving child;

For Tsirk and Brahmin, monk and Jew

Had reached Him through the gods they knew.

It is the deep and sincere wish that all men may reach the full realization that we are indeed all the children of ‘The One Great God’ and conduct ourselves accordingly.

Thus is my message to you – this Christmas day.”

She commented on this poem: “In no way am I prejudiced for or against the various religions of this world. In my eyes they are all good and certainly lead to the same ultimate goal, being the teachings of the Vedas, Zoroaster, Moses, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus or Mohammed. And I am sure that the one Great God counts each and everyone his child and cares little what our theological beliefs and metaphysical opinions may be or the Gods we know and reach Him through. The very fact that we are seeking Him means that we have already found Him. One of our laws should be tolerance of all religions and compassion for all their errors.” (Preface to Autobiography)

Exhibition at the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais” (March 18, 2007 – December 31, 2008)

Johnson Sarah, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais” (?), in Asian Art, April 2007

Johnson Sarah, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais”, in Orientations, May 2007

Lipton Barbara, “History of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art and the Collections”, in Treasures of Tibetan Art: Collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, Oxford University Press, 1996

Marchais Jacques, “Aims and ambitions of Jacques Marchais”, New York, 1938

Marchais Jacques, “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception”, New York, 1938

Marchais Jacques, “The true story of the building of and designing of The Jacques Marchais Center of Tibetan Arts”, New York, 1947

Special thanks to Dr. Sarah Johnson, curator of the Jacques Marchais Museum, for her time and help.

Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World, a Cacophony in Three Acts

Compiler’s Note: Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World was a traveling exhibit from China that appeared in four U.S. museums—the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, the Houston Museum of Natural History, the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco—from October 2003 to September 2005. The controversial exhibit sparked a dialogue about art and politics, but it was a dialogue in which the participants were not always listening to each other. This dialogue, or cacophony, is “reproduced” in part below. The compiler encourages readers to follow the available online links provided in the footnotes to learn more about the exhibit and the issues it raised about museums, politics and culture. (If the links provided do not automatically take you to the correct webpage, copy and paste the link into a new window.)

Act I: Objects

“Almost 200 exquisitely created sacred objects, all with great cultural significance, are making their first journey to the Western World. Tibet: Treasures From the Roof Of The World will offer a rare glimpse into a culture both opulent and deeply spiritual.” [1]

“Now, the Western world will get a firsthand look at the items used in lavish ceremonies and daily rituals at the Potala Palace by the Dalai Lamas and their courts… ‘We’ll see things here that Marco Polo might have seen when he went to Xanadu.'” [2]

“Now, the Western world will get a firsthand look at the items used in lavish ceremonies and daily rituals at the Potala Palace by the Dalai Lamas and their courts… ‘We’ll see things here that Marco Polo might have seen when he went to Xanadu.'” [2]

“Consider a long, slender horn in silver with gilded trim. It is an arresting sight, and so is its stand, with a pair of full-figure skeletons wearing crowns with skull icons encircling them.” [3]

“Consider a long, slender horn in silver with gilded trim. It is an arresting sight, and so is its stand, with a pair of full-figure skeletons wearing crowns with skull icons encircling them.” [3]

“Despite the exoticism of the culture to which they belong, the length of its history and the complexity of the Buddhist cosmology they describe, there’s a casual, hands-on quality to the ensemble. A deeply humane sensibility, and sometimes funky playfulness, runs through all of the Tibetan objects. [4]

“Chinese, Manchu and Tibetan inscriptions carved into this official seal [displayed in the exhibit] express the international stature and importance of the Fifth Dalai Lama. This importance is reflected in the Fifth Dalai Lama’s title, the ‘Buddha of Great Compassion in the West and Leader of the Buddhist Faith beneath the Sky.’ The Fifth Dalai Lama, also known as the Great Fifth, built the Potala Palace and served as both the secular ruler and spiritual teacher of Tibet, a dual role held by each subsequent Dalai Lama. [5]

“Chinese, Manchu and Tibetan inscriptions carved into this official seal [displayed in the exhibit] express the international stature and importance of the Fifth Dalai Lama. This importance is reflected in the Fifth Dalai Lama’s title, the ‘Buddha of Great Compassion in the West and Leader of the Buddhist Faith beneath the Sky.’ The Fifth Dalai Lama, also known as the Great Fifth, built the Potala Palace and served as both the secular ruler and spiritual teacher of Tibet, a dual role held by each subsequent Dalai Lama. [5]

“One of the earliest and most important works in the exhibition, this 12th or 13th century sculpture presents Mahakala, a protector deity worshipped by all Tibetan sects. Wearing a five-skull crown, he has three eyes wide open in enraged expression and his hair stands on end. The orange color of his hair and moustache refers to his function as a wrathful deity, one called upon to protect and defend.” [6]

“One of the earliest and most important works in the exhibition, this 12th or 13th century sculpture presents Mahakala, a protector deity worshipped by all Tibetan sects. Wearing a five-skull crown, he has three eyes wide open in enraged expression and his hair stands on end. The orange color of his hair and moustache refers to his function as a wrathful deity, one called upon to protect and defend.” [6]

“Festive occasions required formal jewelry. This necklace, made of gold, silver, turquoise and coral, was worn by a nobleman. It includes an amulet box, or g’au, which held a Buddhist charm thought to protect the wearer. [7]

“Festive occasions required formal jewelry. This necklace, made of gold, silver, turquoise and coral, was worn by a nobleman. It includes an amulet box, or g’au, which held a Buddhist charm thought to protect the wearer. [7]

Act II: Collisions

“‘From the Tibetan perspective, this is stolen art.'” [8]

“Officials at the Bowers Museum of Cultural Art in Santa Ana insist that their current exhibit, “Tibet: Treasures From the Roof of the World,” is about art, not politics…’It would be inappropriate…for us to take a political stance'” [9]

|

| source:http://www.artnetwork.com/mandala/gallery.html |

“Issue 1:

The censorship and treatment of Tibetan monks, their American representatives, an American Guest curator of the exhibit, and the exhibit’s docents.

A. On September 30, 2003, the imposition of last minute conditions by Bowers Museum Director, Anne Shih, on Ms. Nancy Fireman, Executive Director of Tibetan Living Communities, who was representing a group of Tibetan monks from Southern India. The monks had agreed through Nancy Fireman to a request by Bowers Museum to construct a Sand Mandala (painting) starting October 18, 2003. These last minute conditions included:

1. Prohibiting the Tibetan monks from displaying a portrait of His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama during the creation of the Sand Mandala (painting).

2. Telling the monks that they could not say they were Tibetan refugees visiting from India, but rather that they are from the US.

3. Prohibiting the monks from discussing their refugee status and from distributing literature about their organization, “Tibetan Living Communities,” based in Napa Valley, California, which works towards providing funds for Tibetan refugee settlements in India.

The above conditions led to their subsequent refusal to create the Sand Mandala for the Museum.” [10]

“The Dalai Lama himself didn’t oppose the exhibition. The Bowers Museum’s director, Peter C. Keller, explains, ‘He is for anything that promotes Tibetan culture.'” [11]

|

| 14th Dalai Lama; Source: www.namgyal.org |

“The Bowers Museum…asked the Dalai Lama for permission to display the art. The Dalai Lama granted it, on condition that the Museum describe the art and its historical context fairly. At the same time, he noted that he hoped visitors would come to understand that the culture that produced it is under threat in Tibet.

Nonetheless, the Museum in some respects appears to be bowing to Chinese pressure to prevent the American public from understanding the true implications of the exhibit.” [12]

“To Bartholomew [a curator at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco], setting an altar to Tibet’s Nobel Prize-winning exiled leader in such proximity to artwork on loan from the Chinese government would be a slap in the face for the Chinese.

‘Politics and art need to be kept separate, she says. ‘The Chinese government would definitely close the show.'” [13]

“That Tibetan sacred art is ‘on loan’ to American museums from the Chinese government…the very government that for fifty years has methodically crushed Tibetan culture, only serves to legitimize the military occupation. It’s hard to imagine anyone not understanding the Tibetans who protest against the occupation of their country. It’s easy to sympathize with them when they criticize American museums for so sheepishly providing Beijing with legitimacy regarding its illegal occupation of Tibet. Obviously the Chinese government is exploiting Tibetan art for political gain.” [14]

“Smith sees the exhibit as a chance for the Tibetan diaspora ‘to see parts of their culture that, unless there were museums preserving it and museums exhibiting, would be unavailable’…Jeff Watt, another Rubin curator, urged protesters to set aside their differences and simply feel proud of the display of their heritage.” [15]

“Tethong responds angrily: ‘If Russia had won the cold war and taken over your country, then took the Declaration of Independence on a worldwide tour, how would he feel?'” [16]

“Peter Keller, the Bowers president, shakes his head: ‘I’ve never seen artifacts become this political, this sensitive.” [17]

Act III: Distances

“Transformed into fetishistic art objects unencumbered by explanatory texts, the artifacts lose much of their meaning and significance. It is little wonder that the protesters, many of them holding umbrellas imprinted with the flag of Tibet, chanted ‘shame, shame, shame’ on the street outside of the museum.” [18]

“As a whole, the show is approachable and user friendly…If they [the Tibetan objects] were people, they’d best be described as friendly: not flashy or imperious but a little rough around the edges and optimistic in their openness. This makes for a satisfying exhibition that’s surprisingly intimate, despite having traveled halfway around the world to get here.” [19]

“‘Let’s say your family suffers a home-invasion robbery,” the 56-year-old from Malibu said. ‘Then a museum negotiates with the robbers to display your things. You should be grateful because now you can look at your possessions?'” [20]

“As the exhibit comes to the San Francisco Bay Area…this writer notes that it illustrates how art is never simply an item pinned to a wall but is also an event, and as such enters into a larger cultural dialogue in community.” [21]

“‘What the Asian Art Museum is exhibiting is something the Chinese are using to camouflage their brutal suppression of Tibetan freedom.'” [22]

|

| Chaos in Lhasa, 2008; Source: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23629811/ |

“[Getting the exhibition] was a monster coup for us,” he said. “It is the museum equivalent of winning the Super Bowl.” [23]

“In a letter to the Bowers, the Dalai Lama welcomed the exhibition for revealing the magnitude of Tibet’s artistic traditions. ‘Despite the wholesale destruction that has taken place in Tibet in recent decades,’ he wrote, ‘some works of art have survived. I hope that such efforts will contribute to saving Tibetan culture from disappearing for ever.'” [24]

” An imposing array of valuable cultural relics…prove that Tibet became part of China in the Yuan Dynasty and has remained under the administration of the central government of China since then.” [25]

“Xerab Nyima, a Tibetan scholar, said it is irrefutable that Tibet has not been separate from the motherland since it came under the rule of the Yuan Dynasty 700 years ago. However, the Dalai Lama and some people in the west still preach the independence of Tibet. It is ridiculous, he said.” [26]

|

| Mao; Source: www.britannica.com |

“Greater exposure to Tibet’s artistic glories will likely advance its cause as a rich culture and a people that deserves

better than forced rule and human-rights abuses at the hands of the Chinese.

|

| Sourcehttp://tibet.hmns.org/ |

One facet of Tibetan culture that surely troubled Mao’s China was the inseparability of religion and art, and of religion and the political structure. This is abundantly evident in the exhibition.” [27]

Works Cited

Act I: Objects

[1] This description is from the home page of the exhibition at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. See http://www.asianart.com/exhibitions/bowers/index.html

[2] Associated Press, “Historic agreement brings Tibetan treasures to U.S.,” CNN Online, October 16, 2003. http://www.cnn.com/2003/TRAVEL/DESTINATIONS/10/12/tibetan.treasures.ap/

[3] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html

[4] David Pagel, “Tibet’s treasures seen on a human scale; An exhibition of jewelry, sculptures and everyday artifacts in Santa Ana is unpretentious yet impressive,” Los Angeles Times, October 31 2003. The article is accessible online through ProQuest.

[5] This description of one of the object’s in the museum and the two that follow it were used by the Houston Museum of Natural Science. See http://tibet.hmns.org/images/selections(t).pdf See also the home page of the exhibition at the Houston Museum of Natural Science: http://tibet.hmns.org/ The Houston Museum website includes downloadable images (under the heading “Press”) and all of the images that appear in Act I of this dialog are from this site. Also of interest is the descriptions of the Adult Education Programs offered by the museum in conjunction with the exhibition, especially the panel “Modern Tibet: The Legacy of the Past ad Challenges of the Future,” which included a discussion of Tibet’s contemporary political situation.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

Act II: Collisions

[8] This statement was made by Denis Cusack, “a board member of the Tibet Justice Center, which advocates an independent Tibet.” See Associated Press, “Historic agreement brings Tibetan treasures to U.S.,” CNN Online, October 16, 2003. http://www.cnn.com/2003/TRAVEL/DESTINATIONS/10/12/tibetan.treasures.ap/

[9] Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2 The individual quoted in this citation is Rick Weinberg, the director of public relations and marketing for the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana.

[10] “Bowers Tibet Exhibit Update: Issues Raised by the Southern California Tibetan Community and Tibet Supporters with Suggested Corrective Action by Bowers Museum of Cultural Art,” Los Angeles Friends of Tibet website, http://www.latibet.org/Bowers/bowers-issue.htm The image of the monk creating a sand mandala is from http://www.artnetwork.com/mandala/gallery.html This sand mandala was made for the California Museum of Art in 2001.

[11] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html Peter C. Keller is the president of the Bowers Museum.

[12] “Tibetan Rights Group Calls Bowers Museum Exhibit Stolen Art,” Tibet Justice Center Website, http://www.tibetjustice.org/press/03.10.13-bowers.html

[13] Lisa Tsering, “Activists Blast SF Museum’s Exhibit of Tibetan Art,” Asian-American Village News, http://www.imdiversity.com/Villages/Asian/arts_culture_media/pns_tibet_art_0605.asp

[14] Mark Vallen, “Stolen Art & Cultural Destruction,” Mark Vallen’s “Art for a Change” Weblog, http://www.art-for-a-change.com/blog/2005/04/stolen-art-cultural-destruction.html This is a weblog by a working artist. He discusses the Tibet exhibit and compares it to an exhibition of Iraqi artifacts called The Gold of Nimrud: Treasures of Ancient Iraq.

[15] Sue Morrow Flanagan, “Treasures in cultural crossfire,” Financial Times (London), April 4, 2005. Online at http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2005&m=4&p=4_4

[16] Ibid. Lhedon Tethong is executive director of Students for a Free Tibet.

[17] Ibid.

Act III: Distances

[18] Jennie Klein, “Being Mindful: West Coast Reflections on Buddhism and Art,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 27.1 (2005), pp. 82-90. Available online at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/performing_arts_journal/v027/27.1klein.html [Access may be limited].

[19] David Pagel, “Tibet’s treasures seen on a human scale; An exhibition of jewelry, sculptures and everyday artifacts in Santa Ana is unpretentious yet impressive,” Los Angeles Times, October 31 2003. The article is accessible online through ProQuest.

[20] Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2 The individual quoted is Tseten Phanucharas, one of the many people who protested the exhibition at the Bowers Museum.

[21] Gary Gach, “Note on San Francisco Venue,” http://www.asianart.com/exhibitions/bowers/note.html From the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco website.

[22] This comment was made by Topden Tsering, head of the Bay Area branch of the Tibetan Youth Congress. See Lisa Tsering, “Activists Blast SF Museum’s Exhibit of Tibetan Art,” Asian-American Village News, http://www.imdiversity.com/Villages/Asian/arts_culture_media/pns_tibet_art_0605.asp

[23] This comment was made by Rick Weinberg, the director of public relations and marketing for the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana. Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2

[24] Sue Morrow Flanagan, “Treasures in cultural crossfire,” Financial Times (London), April 4, 2005. Online at http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2005&m=4&p=4_4

[25] “Tibet Becomes Part of China 700 Years Ago,” Peoples Daily. http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200105/14/eng20010514_69926.html The “relics” mentioned in this quotation include many that were on display in the Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World Exhibit. The author of this article, however, is referring to an exhibition put on at the Sagya Monastery in Lhasa.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html

by Hojeong Choe

The Hahn Cultural Foundation was founded by Dr. Kwang-ho Hahn in 1992, when the foundation was registered to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Korea.

Dr. Hahn, a current Honorary Chairman of the museum, has begun collecting the curios in 1960s and…

Hwajeong Museum , Seoul, Korea

Namio Egami (江上波夫, 1906-2002)

Kimiaki Tanaka (田中公明, 1955-)

The part of the collection can be also viewed on the Himalayan Art Resources website.[Hahn at HAR ]

| Tibetan Silk Dancing Dress (American Museum of Natural History) |

The Robe

The sleeves are identically decorated, each with three distinct horizontal patterns. Closest to the shoulder is a wide strip of dark grey silk brocaded with multi-color and metal dragons, clouds and various symbols. This is followed by a slimmer strip of bright red silk damask. After which is slightly wider strip of bright red, green, purple and pastel damask clouds diamonds sitting within squares. This marks the half-way point, at which the bright red silk damask pattern repeats, followed by a narrow strip of the dark grey silk brocaded pattern.

The pointed sleeves of robe are characteristic of a costume that would have been worn during a masked dance performance that would take place at a Tibetan Monastery. The sleeves would resemble normal sleeves, except that hanging triangular cloth allows them to undulate gracefully while dancers swing a gesture flamboyantly with their arms [1].The width across the sleeves is 168 cm (about 5.5 feet).

The upper part of the robe is quite plain because it is intended to be embellished by other parts of the dancing costume [2]. The body of dark grey silk is worn and threadbare, with holes and tarnished metallic threads. The costume is lined with dark red cotton.

A white silk ribbon, embroidered with houses, people, lotus flowers and trees and other domestic images emphasizes the waistline. The trimming leads to a very full skirt; the lower part of the robe is decorated with patterns resembling those on the sleeves. The length of the robe is 108 cm (about 3.5) and it flows out below the knees.

Dragons

| Chinese Dragons |

The four-clawed dragon that appears on the skirt and part of each of the sleeves is, “normally associated with nobles and imperial officials from the Chinese court [7].” The dragon symbolizes good fortune, power and success. Scholars believe that this motif may have “found its way to Tibet through the gifts of silks and embroideries that the emperors of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) regularly sent to the monasteries[8].”

| Gyatso, “In the Sacred Realm,” in Reynolds 1999. From the Sacred Realm, 171-179, “Symbols,” 254-261. (9 pp text) |

Clouds

| Silk Embroidered with Cloud Motif |

Along the strip of dark grey silk, closest to the shoulder are multi-colored clouds. The cloud motif represents the whole universe or a part of the foundation of the universe. “In the Ch’ing dynasty this symbolism was quite obvious, especially on the dragon robes, where the cloud-studded upper part of the garment represented the canopy of the sky, supported on the world as indicated by the mountains and seas at the base of the robe. But even earlier when the actual decoration did not demonstrate this so clearly, the robe was thought to represent the all-encompassing sky [9].”The cosmic symbolism of the robe itself seems to indicate that the wearer has achieved qualities of the celestial by surpassing worldly existence and achieving purity of mind. One may notice that the representation of the cloud is similar to the omnipresent lotus flower motif.

Festive Dancing & Dress

The British Museum has an item that is similar this dress, donated by the Government of India (see below). The costume is from Tibet, during the late 19th or early 20th century. At this time, “most monasteries in Tibet had a collection of masks and elaborate silk costumes, which were brought out for performances during a variety of celebrations [18].” Examples of the types of festival at which this ceremonial dress would have been worn are Losar, the Tibetan New Year or Saka Dawa, the celebration of Buddha’s enlightenment. See the object biography of the Deer Mask for more examples of the masks and costumes associated with such festivals.

| Silk Dancing Dress (The British Museum) |

Saka Dawa Festival

In the Tibetan calendar, it is traditional for Tibetans to celebrate the day when, “Sakyamuni was born, achieved nirvana and passed away [19].” It is a long established custom among Tibetans to dress in their best clothing and “assemble at the Dragon King Pool behind the magnificent Potala Palace to celebrate this grand religious festival [20].” This practice has developed into a large gala during which Tibetans visit parks and pray for a good harvest. “During this festival, some people set up colorful tents; some prepare barley wine and butter tea, families resting beside the pool with great joy. Then young Tibetans dance in a circle while singing following the rhythm by stamping their feet [21].”

Tibetan New Year

Tibetans prepare for the important ceremonies which surround the New Year for weeks prior to the event. During their preparations, Tibetans infuse barley seeds in basins. On the eve of the holiday, a variety of foods are presented to images of Buddha. Traditionally, on the first day of the celebration, one family member is sent to take a barrel of water home from the river, the first barrel of water in the New Year is called auspicious water [22]. The second day signals the beginning of the social visits which friends and family make to one another. During the 3-5 days following, there is festive dancing, “at the squares or open grasslands with the accompaniment of guitars, cymbals, gongs and other musical instruments. Hand in hand, arm in arm, Tibetans dance in a circle while singing following the rhythm by stamping their feet. Children, on the other hand, will fire firecrackers. A happy, harmonious and auspicious festival atmosphere will pervade the whole area [23].”

Song and Dance

Each region of Tibet had its own, distinct style as well as songs and dances. “The most ancient songs are sung without any accompaniment and one can imagine them being sung high in the mountains as shepherds took care of the animals [24].”

| Cham |

Those dances performed at religious institutions follow different customs than those practiced by common folk. Religious dances customarily depict aspects of the Buddhist philosophy. “They can be amazingly spectacular, involving the use of masks, extremely colourful costumes, and the playing of horns, cymbals, and other traditional Tibetan instruments [25].” The elaborately decorated masks and color give the costume a striking overall appearance.

Ordinary Tibetan Dress

| Back View of Chuba |

| Front View of Chuba |

“In most areas the traditional dress for both men and women consists of the chuba, a long wrap-around cloth tied at the waist, with men tending to wear a shorter chuba with pantaloons. There are many distinctive variations in how the chuba is worn, each indicating the wearer’s area or a particular symbolic significance [26].”

[1] http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/s/silk_dancing_dress.aspx</span>

[2] IBID.

[7] http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/s/silk_dancing_dress.aspx

[8] IBID.

[9] The Symbolism of the Cloud Collar Motif by Schuyler Cammann P 5

[18] http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/s/silk_dancing_dress.aspx</span

[19] [[http://www.tibettravel.info/lhasa/lhasa-festivals.html%3C/span%3E%3C/span|http://www.tibettravel.info/lhasa/lhasa-festivals.html</span]]

[20] IBID.

[21] IBID.

[22] IBID.

[23, 24, 25, 26] http://www.rokpauk.org/tibcultureheritage.html

| Chinese Cloud Collar with extra folliations, Johns Hopkins University Museum |

| Simple Chinese Cloud Collar, Johns Hopkins University Museum |

This object, which lives in a drawer in the American Museum of Natural History, is a hollowed out animal horn and was probably used in traditional Tibetan medicine for cupping. Although the AMNH labels it as a bleeding cup, my research indicates that it probably was not used to hold blood, though the process of cupping involves moving blood to certain identified areas of the body.

The most convincing evidence that this horn was used for cupping can be found in the image below, a plate from the book “Tibetan Medicine”.

“Plate No. 17

A Tibetan doctor’s medicine bag made of leather and silk brocade, where he keeps his medicines and instruments. Each powder is kept in a little leather bag with a bone label as shown. The bag in the Wellcome library is 9 inches high and the diameter at the bottom measures 10 inches. It contains fifty little bags with powders. Spoon for measuring medicines. Instruments for taking off a cataract. An ox’s horn used for cupping. Medicinal stone. A cow’s horn with a small hole at the tip, through which the doctor sucks blood from the diseased area. (Tibetan Medicine, 132)”

The small ox horn to the right of the medicine bag pictured closely resembles the AMNH’s horn. This horn was included in the medicine bag of a Tibetan doctor. Further evidence that this horn was not used for bleeding comes from the section on surgical instruments which describes another object used for bloodletting: “For removing bad blood and pus from affected parts of the body, a round copper bowl, 4 inches in diameter” (Tibetan Medicine, 84).

Common to these sytems of thought is a construction of the body as a microcosm of the natural universe. To this largely naturalisitc system of theory and practice, early Tibetan medical scholars added Buddhist notions of the mind or self, emotion, and the law of karma, developing a theoretical system in which the notion of a mental self (sems) was constituted as dominant over the objective, or grossly physical, body…Thus, Buddhist medicine posits that the self (the “ego”) is ultimately causal of all suffering, including that of ill health. Although body and mind are seen as fundamentally integreated in this sytem, it is the mind that problematized and seen as primary in faciliatating both health and ill health (The Transformation of Tibetan Medicine, 10).

Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Chart indicating good and bad bloodletting days and when to guard against demons. The chart also contains a sme ba, 9 figures symbolizing the elements in geomancy, in the center with the Chinese pa-kua, 8 trigrams, surrounded by 12 animals representing months and years. Below this, symbols of the 7 days of the week. 106 compartments containing an ornamental letter in each and written in dbu indicate bloodletting days. The protector deities, top, are Manjursri, the White Tara and Vajrapani, below them the 8 fortune signs and other symbols.

Collection: Asian Collection

Horns have been used medicinally for millenia, most notably by the Chinese. “The horn of rhinoceros dries pus and purifies the blood; antelope’s horns is used in medicines that diarrhea; wild yak’s horn cures tumours and gives warmth to the body; the horn of argali (Asiatic wild sheep) protects against contagious diseases; wild sheep’s and Saigo antelope’s horn assist easy birth. Crocodile’s claws cure bone fever. Snail’s shell cures dropsy and stomach diseases” (Tibetan Medicine, 71)

While the specific circumstances of this object’s history are unavailable, it is interesting to note the acquisition dates, 1920-1953, that are listed in the object’s catalogue information. These dates correspond to the end of a period of significant missionary activity in Tibet, which played an important role in the growth of many museum’s Tibetan collections. The Newark Museum, which houses a prominent collection of Tibetan objects, was born from the work of the medical missionary Albert Shelton, who spent periods of several years living in Tibet with his wife and family. When Shelton met Dr. Edward Crane in 1910, a founding trustee of the Newark Museum, on his return voyage from a six year mission in Tibet, they became friends and he eventually sold his personal collection of Tibetan objects to the museum. Dr. Shelton was not the only missionary in Tibet during the time period.

Between 1928 and 1948 three more missionary collections, all from north-eastern Tibet were purchased, greatly enhancing the Museum’s holdings of ethnographic and ceremonial art. These were the Robert Ekvall collection, from the Kokonor nomad region, Amdo, 1928, the Carter D. Holton collection from Labrang, Amdo, 1936, and the Robert Roy Service collection, formed during trips to northeastern Tibet and acquired from Chinese traders in the border areas, 1948. Holton and his colleague, the Re. M.G. Griebenow, worked at the American-sponsored Christian and Missionary Alliance Mission at Labrang.

The American Museum of Natural History, in the catalogue information, lists the donor as “Marx”. Dr. Karl Marx was a missionary in Tibet at the end of the 19th century and while he is less well known that Dr. Albert Shelton, the ANMH’s Asian Ethnographic Collection website, which pictures their collection of objects, lists 167 other objects with the donor name “Marx” in the Tibetan collection. This includes medicine bags, a medicine spoon, etc.

The route map of Captain W.J. Gill’s journey in Western China and Eastern Tibet

“Tibetan Medicine, already under pressure to modernize in the early 20th c. as a result of the 13th Dalai Lama’s efforts to centralize political power and authority, has become mired in these larger Chinese-Tibetan conflicts by virtue of its culturally significant and religiously salient position in Tibetan society” (pg 7)

BLEEDING CUP

ASIAN ETHNOGRAPHIC COLLECTION

Catalog No:

70.0/ 2107

Culture:

TIBETAN

Country:

TIBET

Material:

HORN

Dimensions:

L:9.3 W:5 H:3.6 [in CM]

Donor:

MARX

Accession No:

1920-53

I

http://skepticwiki.org/index.php/Life_of_St_Issa#Dr_Karl_Marx

This is an image of the late 17th/early 18th century Tibetan visionary Terdag Lingpa as depicted in a fresco within the main temple of Mindroling monastery in Dranang valley of the Lhoka region, Central Tibet. This reproduction was published in a pamphlet form introduction and outline of Terdag Lingpa’s collected works by the branch of Mindroling in Dehra Dun, India. http://www.mindrolling.com/ The painting is credited to his younger brother, the great scholar and artist Lochen Dharmashri. Unfortunately, the inscription on the original painting is obscured. The inscription in the reproduction says simply, “An image of the Terton painted by Lochen Dharmashri.” Note the eyeglasses resting on Terdag Lingpa’s forehead. While it is not impossible that Terdag Lingpa had and wore spectacles, the presence of these eyeglasses is unusual and striking as compared with other portraits from the same historical context. Given the rarity of eyeglasses in Tibetan portraits, these eyeglasses are curious.

The history of eyeglasses in the Western world extends back to the 13th Century. Some thoughts on the history of eyeglasses in Europe.

There are many possible explanations for the presence of these eyeglasses. Did Terdag Lingpa wear them to aid his vision, as eyeglasses are conventionally worn? Are they not eyeglasses as we know them, but a ritual implement used in meditative exercises or to enhance visionary experiences? Are they a novelty or luxury item that the artist chose to include because they highlighted Terdga Lingpa’s elevated status? Were eyeglasses available or even common in Terdag Lingpa’s time, but not typically depicted in images of lamas — the most frequent subjects of portraits — perhaps since eyeglasses would be a sign of poor vision and therefore not flattering to the lama’s image?

There are other images of lamas wearing eye coverings of one variety or another. Here are some examples of eye coverings in depictions of Kagyu and Sakya lamas. These images, compiled by Jeff Watt in response to my query about eye coverings in Himalayan art, depict lamas identified as part of the Karma Kagyu, Drukpa Kagyu and Sakya lineages. The paintings and sculpture are approximately dated from 1500-1799. These images might indeed be of the same category as the eyeglasses in Lochen Dharmashri’s portrait of Terdag Lingpa, but they are markedly different in appearance. Terdag Lingpa’s resemble modern day eyeglasses far more than any of these other images. This makes me wonder whether the eyeglasses depicted in the Mindroling portrait might have been a gift from a foreign guest or patron, or a pilgrim who had traveled abroad and who delivered them to Terdag Lingpa.

According to China historian Milton Walter Meyer, eyeglasses were imported to China from Europe through Southeast Asia as early as the Tang. Meyer claims the by late Imperial times, spectacles were a common accoutrement of the literati. At certain points, eyeglasses were also a sign of prestige in Europe. It is possible that Terdag Lingpa’s eyeglasses came from China, and the fact that Lochen Dharmashri chose to include them in the portrait might suggest that they were a mark of prestige in the Tibetan context as well.

Bibliography

Illardi, Vincent. 2006 Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

— “Eyeglasses and Concave Lenses in Fifteenth-Century Florence and Milan,” Renaissance Quarterly, 29 (1976), 341-60.

— “Renaissance Florence: The Optical Capital of the World” Journal of European Economic History 22 (1993), 507-41.

Lindberg, David C. “Lenses and Eyeglasses” Dictionary of the Middle Ages vii. 538-41.

Meyer, Milton W. 1997. Asia: a concise history. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Rosen, Edward. “The Invention of Eyeglasses,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 11 (1956), 13-46, 183-218.

|

| The object to scale next to a pencil |

This object is small, about 2 inches in diameter and thickness. There are approximately two-hundred and sixty individual sheets of Tibetan paper tied together with a piece of stiff sinew. The sinew is tied in a square knot. Some of the leaves are not stacked neatly; in some places up to five of the leaves and folded inside of each other. The object fits nicely in the palm. Each of the leaves is block-printed on Tibetan paper with the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum which repeats itself again and again around the circle. The object smells musty and brown mold is visible in a few places. The object is compact and sturdy and from my observations it appears that it was constructed in its present shape and form to serve a functional purpose rather than decorative; this is not an object to display though it may have been part of an object that did have aethestic value. I unfortunately did not taste the object, however if were able to scientifically “taste” the object by taking a sample of its fibers we might be able to further understand when exactly this object was made and from what plants the paper comes from.

While it is only possible to speculate, after a fair amount of research and conversations, I have determined that this object may be a collection of individual prayer leaves that, rather than being placed as a unit inside the body of the prayer wheel, would be used individually at the top and bottom of the prayer wheel to lock in the scroll. I was finally able to determine this after finding a diagram of how to make a mani wheel in Lorne Ladner’s book Wheel of Great Compassion (see images below). He writes, “the instructions here conform to the method suggested by the Fourth Panchan Lama (link), which Lama Zopa Rinpoche has said is a correct method for filling mani wheels” (The Wheel of Great Compassion, 87).

|

| Step two |

|

| Step one |

Below, Lama Zopa Rinpoche has actually drawn a version of earth wheel, which is to be fitted on the bottom of the scroll. The second piece, the sky wheel, fits on the top.

It is believed in Tibetan Buddhism that spinning the written form of Om Mani Padme Hum around a prayer wheel, otherwise known as a mani wheel, has the same effect as repeating the mantra out loud and thus the spinner can accrue merit . The prayer wheel is used as a meditation tool.

However, the formal function of this object (or rather, the function of one of its elements, the prayer leaves) that I have named does not mean that this particular bundle of prayer leaves was used for that purpose. To determine where this object might have traveled before its current home on a numbered shelf in the Museum of Natural History in New York City, it is helpful to consider the tactile experience that I and others had when we were able to spend time with the object on February 28, 2008. Mostly notably, after twenty minutes of (gloved) handling of the object, where we counted the leaves and rifled through them to understand their motion and composition, the object degenerated quite a bit; the leaves, particularly those close to the top and bottom, were considerably more wrinkled and worn than when we first picked it up. This signifies that the object has not been handled by human hands very frequently, if at all, since it was constructed. This experience with the object might lead one to believe one of two things: that the object is fairly old and, while it may have been handled frequently by its original owner (or one of its owners), is now in a state of disintegration, or, that the object has always been stored away from human hands, possibly even inside a prayer wheel to take the place of the traditional scrolled mantra. This seems possible because the prayer leaves are pierced in their center and appear to have been compactly held together for a significant period of time; the ink on some of leaves is bleeding and smudged onto other leaves. What is nearly for certain is that these leaves were intended to be spun, either together in their current form or separately as the top and bottom pieces of more conventional prayer wheels, so that the mantra could accrue merit for its spinner.

|

| Prayer Bundle Side View |

I am not the first person to posit this question; in 1896 William Simpson published the book The Buddhist Praying Wheel after visiting Tibet. He first recounts his experience with the Buddhist praying wheel and then goes on to describe The Wheel-God in France; the Whirling Dervishes of Cairo, Egypt; the Ka’bah at Mekkah; the Japanese Wheel with Thunder Drums; Wheels with Charms attached, found in Swiss Lake-Dwellings; his list goes on. I have included images of other Tibetan Buddhist uses of the wheel or circle as well as a discussion of a few other examples that he gives.

|

| Similiar object found in a bug-infested statue |

|

| Vajravarahi Abhibhava Mandala |

Unknown Block-Printed Mantra from statue, AMNH Vajravarahi Abhibhava Mandala 14th c.

First, within Tibetan Buddhism We looked at the object above during the same time that we looked at the Bundle of Prayer Leaves at the American Museum of Natural History; it had been found inside a statue of the Buddha that had been taken apart due to bug infestation.

|

| Whirling Dervishes, Turkey |

Whirling Dervishes of the Mevlevi Order; Istanbul, Turkey

X. Theordore Barber, in his 1986 article in Dance Chronicle entitled, Four Interpretations of Mevlevi Dervish Dance, 1920-1929, writes:

“Few dances are as famous as the whirling of the Mevlevi dervishes. For many centuries, despite Orthodox Islam’s opposition to dance, some orders of dervishes, or mystics, have employed dance movements in their ceremonies. Each order, congregating in its lodge, or tekke, had its own unique movements meant to induce an ecstatic or trancelike state. In unison, the dervishes would do such things as sway back and forth, turn in a circle while holding each other, or jump at set intervals, all the while repeating the name of God (Allah). Musicians and even singers would often accompany these actions. Yet no dervish sect has fascinated the West more than the Mevlevis, who whirled like tops in the course of their rite.”

|

| Ka’bah |

Ka’bah; Mecca, Saudi Arabia

The Ka’bah is a cube-shaped building at the center of the al-Masjid al-Haram mosque in Mecca. It is considered the most holy place in Islam and during the Hajj, or yearly pilgramage, millions of pilgrams circumambulate around the Ka’bah.

Click here to watch the Youtube video “Inside Mecca, view of Kaaba” to see footage of the actual circling of the Ka’bah.

|

| {a} Photo from the AMNH Collections Database China: Tibetan |

Here is a deer mask.

It’s come a long way–100 years and some 7,000 miles–from its birthplace in Tibet to its current residence in New York City. Even so, it was created for education and entertainment and it maintains this same purpose today, if in a different way. This biography begins to tell its story. Moving in reverse, it traces the mask’s movement to the American Museum of Natural History from cultural Tibet.

As with the story of any object, the story of this particular mask stands as a point of intersection among countless other stories that crisscross time and space: monastic dance, the cataloging impulse, animal deities, religious conflict, art technology, ritual guises, and expeditions to Asia, to name a few. This preliminary project plucks a few of these strands and see which other strands they tug on.

The stag mask here is made of paper mache, with eyes of glass or possibly plastic. It is a mask meant to be worn over the entire head and measures approximately 18 inches long, 19 inches wide and 20 inches high, not including the antlers, which are about 18 inches long. Since it is made of paper mache, it is surprisingly light weig

|

| {b} Click image to view larger |

ht for its size. This is essential to its use, which is in vigorous, spinning dance. A red cloth collar is attached to the bottom of the mask in the front and back. The dancer would be able to see out of the open mouth, but the field of vision is quite limited .

The style of the mask is naturalistic, which contrasts with many other Tibetan monastic masks that look like animals. See, for example, the deer mask from Mongolia pictured on the right. (Click on the image for a larger photo) The third eye, the skull on the crown, and the gold flaming designs shaped like eyebrows and facial hair set this deer apart from earthly deer. The museum’s stag mask also has flame-like gold designs emanating from the corners of its mouth (pictured at above) but they are much more subdued . The red band around the mouth suggests gums as if the lips are drawn back in an expression characteristic of some deities. However, the deer’s teeth are small and relatively flat like an ordinary deer’s and there is no tongue curling upward as there often is in wrathful figures, such as the pictured Mongolian deer mask. For these reasons, it is not possible to say with certainty what exactly the mask was made to be used for: opera or monastic dance. However, the expedition field notes place the mask among masks generally associated with monastic dance rather than opera and the museum has hung an almost identical mask in a monastic dance mask display, which I discuss below.

Its Life as an Artifact ~1908-2008