Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World, a Cacophony in Three Acts

Compiler’s Note: Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World was a traveling exhibit from China that appeared in four U.S. museums—the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, the Houston Museum of Natural History, the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco—from October 2003 to September 2005. The controversial exhibit sparked a dialogue about art and politics, but it was a dialogue in which the participants were not always listening to each other. This dialogue, or cacophony, is “reproduced” in part below. The compiler encourages readers to follow the available online links provided in the footnotes to learn more about the exhibit and the issues it raised about museums, politics and culture. (If the links provided do not automatically take you to the correct webpage, copy and paste the link into a new window.)

Act I: Objects

“Almost 200 exquisitely created sacred objects, all with great cultural significance, are making their first journey to the Western World. Tibet: Treasures From the Roof Of The World will offer a rare glimpse into a culture both opulent and deeply spiritual.” [1]

“Now, the Western world will get a firsthand look at the items used in lavish ceremonies and daily rituals at the Potala Palace by the Dalai Lamas and their courts… ‘We’ll see things here that Marco Polo might have seen when he went to Xanadu.'” [2]

“Now, the Western world will get a firsthand look at the items used in lavish ceremonies and daily rituals at the Potala Palace by the Dalai Lamas and their courts… ‘We’ll see things here that Marco Polo might have seen when he went to Xanadu.'” [2]

“Consider a long, slender horn in silver with gilded trim. It is an arresting sight, and so is its stand, with a pair of full-figure skeletons wearing crowns with skull icons encircling them.” [3]

“Consider a long, slender horn in silver with gilded trim. It is an arresting sight, and so is its stand, with a pair of full-figure skeletons wearing crowns with skull icons encircling them.” [3]

“Despite the exoticism of the culture to which they belong, the length of its history and the complexity of the Buddhist cosmology they describe, there’s a casual, hands-on quality to the ensemble. A deeply humane sensibility, and sometimes funky playfulness, runs through all of the Tibetan objects. [4]

“Chinese, Manchu and Tibetan inscriptions carved into this official seal [displayed in the exhibit] express the international stature and importance of the Fifth Dalai Lama. This importance is reflected in the Fifth Dalai Lama’s title, the ‘Buddha of Great Compassion in the West and Leader of the Buddhist Faith beneath the Sky.’ The Fifth Dalai Lama, also known as the Great Fifth, built the Potala Palace and served as both the secular ruler and spiritual teacher of Tibet, a dual role held by each subsequent Dalai Lama. [5]

“Chinese, Manchu and Tibetan inscriptions carved into this official seal [displayed in the exhibit] express the international stature and importance of the Fifth Dalai Lama. This importance is reflected in the Fifth Dalai Lama’s title, the ‘Buddha of Great Compassion in the West and Leader of the Buddhist Faith beneath the Sky.’ The Fifth Dalai Lama, also known as the Great Fifth, built the Potala Palace and served as both the secular ruler and spiritual teacher of Tibet, a dual role held by each subsequent Dalai Lama. [5]

“One of the earliest and most important works in the exhibition, this 12th or 13th century sculpture presents Mahakala, a protector deity worshipped by all Tibetan sects. Wearing a five-skull crown, he has three eyes wide open in enraged expression and his hair stands on end. The orange color of his hair and moustache refers to his function as a wrathful deity, one called upon to protect and defend.” [6]

“One of the earliest and most important works in the exhibition, this 12th or 13th century sculpture presents Mahakala, a protector deity worshipped by all Tibetan sects. Wearing a five-skull crown, he has three eyes wide open in enraged expression and his hair stands on end. The orange color of his hair and moustache refers to his function as a wrathful deity, one called upon to protect and defend.” [6]

“Festive occasions required formal jewelry. This necklace, made of gold, silver, turquoise and coral, was worn by a nobleman. It includes an amulet box, or g’au, which held a Buddhist charm thought to protect the wearer. [7]

“Festive occasions required formal jewelry. This necklace, made of gold, silver, turquoise and coral, was worn by a nobleman. It includes an amulet box, or g’au, which held a Buddhist charm thought to protect the wearer. [7]

Act II: Collisions

“‘From the Tibetan perspective, this is stolen art.'” [8]

“Officials at the Bowers Museum of Cultural Art in Santa Ana insist that their current exhibit, “Tibet: Treasures From the Roof of the World,” is about art, not politics…’It would be inappropriate…for us to take a political stance'” [9]

|

| source:http://www.artnetwork.com/mandala/gallery.html |

“Issue 1:

The censorship and treatment of Tibetan monks, their American representatives, an American Guest curator of the exhibit, and the exhibit’s docents.

A. On September 30, 2003, the imposition of last minute conditions by Bowers Museum Director, Anne Shih, on Ms. Nancy Fireman, Executive Director of Tibetan Living Communities, who was representing a group of Tibetan monks from Southern India. The monks had agreed through Nancy Fireman to a request by Bowers Museum to construct a Sand Mandala (painting) starting October 18, 2003. These last minute conditions included:

1. Prohibiting the Tibetan monks from displaying a portrait of His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama during the creation of the Sand Mandala (painting).

2. Telling the monks that they could not say they were Tibetan refugees visiting from India, but rather that they are from the US.

3. Prohibiting the monks from discussing their refugee status and from distributing literature about their organization, “Tibetan Living Communities,” based in Napa Valley, California, which works towards providing funds for Tibetan refugee settlements in India.

The above conditions led to their subsequent refusal to create the Sand Mandala for the Museum.” [10]

“The Dalai Lama himself didn’t oppose the exhibition. The Bowers Museum’s director, Peter C. Keller, explains, ‘He is for anything that promotes Tibetan culture.'” [11]

|

| 14th Dalai Lama; Source: www.namgyal.org |

“The Bowers Museum…asked the Dalai Lama for permission to display the art. The Dalai Lama granted it, on condition that the Museum describe the art and its historical context fairly. At the same time, he noted that he hoped visitors would come to understand that the culture that produced it is under threat in Tibet.

Nonetheless, the Museum in some respects appears to be bowing to Chinese pressure to prevent the American public from understanding the true implications of the exhibit.” [12]

“To Bartholomew [a curator at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco], setting an altar to Tibet’s Nobel Prize-winning exiled leader in such proximity to artwork on loan from the Chinese government would be a slap in the face for the Chinese.

‘Politics and art need to be kept separate, she says. ‘The Chinese government would definitely close the show.'” [13]

“That Tibetan sacred art is ‘on loan’ to American museums from the Chinese government…the very government that for fifty years has methodically crushed Tibetan culture, only serves to legitimize the military occupation. It’s hard to imagine anyone not understanding the Tibetans who protest against the occupation of their country. It’s easy to sympathize with them when they criticize American museums for so sheepishly providing Beijing with legitimacy regarding its illegal occupation of Tibet. Obviously the Chinese government is exploiting Tibetan art for political gain.” [14]

“Smith sees the exhibit as a chance for the Tibetan diaspora ‘to see parts of their culture that, unless there were museums preserving it and museums exhibiting, would be unavailable’…Jeff Watt, another Rubin curator, urged protesters to set aside their differences and simply feel proud of the display of their heritage.” [15]

“Tethong responds angrily: ‘If Russia had won the cold war and taken over your country, then took the Declaration of Independence on a worldwide tour, how would he feel?'” [16]

“Peter Keller, the Bowers president, shakes his head: ‘I’ve never seen artifacts become this political, this sensitive.” [17]

Act III: Distances

“Transformed into fetishistic art objects unencumbered by explanatory texts, the artifacts lose much of their meaning and significance. It is little wonder that the protesters, many of them holding umbrellas imprinted with the flag of Tibet, chanted ‘shame, shame, shame’ on the street outside of the museum.” [18]

“As a whole, the show is approachable and user friendly…If they [the Tibetan objects] were people, they’d best be described as friendly: not flashy or imperious but a little rough around the edges and optimistic in their openness. This makes for a satisfying exhibition that’s surprisingly intimate, despite having traveled halfway around the world to get here.” [19]

“‘Let’s say your family suffers a home-invasion robbery,” the 56-year-old from Malibu said. ‘Then a museum negotiates with the robbers to display your things. You should be grateful because now you can look at your possessions?'” [20]

“As the exhibit comes to the San Francisco Bay Area…this writer notes that it illustrates how art is never simply an item pinned to a wall but is also an event, and as such enters into a larger cultural dialogue in community.” [21]

“‘What the Asian Art Museum is exhibiting is something the Chinese are using to camouflage their brutal suppression of Tibetan freedom.'” [22]

|

| Chaos in Lhasa, 2008; Source: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23629811/ |

“[Getting the exhibition] was a monster coup for us,” he said. “It is the museum equivalent of winning the Super Bowl.” [23]

“In a letter to the Bowers, the Dalai Lama welcomed the exhibition for revealing the magnitude of Tibet’s artistic traditions. ‘Despite the wholesale destruction that has taken place in Tibet in recent decades,’ he wrote, ‘some works of art have survived. I hope that such efforts will contribute to saving Tibetan culture from disappearing for ever.'” [24]

” An imposing array of valuable cultural relics…prove that Tibet became part of China in the Yuan Dynasty and has remained under the administration of the central government of China since then.” [25]

“Xerab Nyima, a Tibetan scholar, said it is irrefutable that Tibet has not been separate from the motherland since it came under the rule of the Yuan Dynasty 700 years ago. However, the Dalai Lama and some people in the west still preach the independence of Tibet. It is ridiculous, he said.” [26]

|

| Mao; Source: www.britannica.com |

“Greater exposure to Tibet’s artistic glories will likely advance its cause as a rich culture and a people that deserves

better than forced rule and human-rights abuses at the hands of the Chinese.

|

| Sourcehttp://tibet.hmns.org/ |

One facet of Tibetan culture that surely troubled Mao’s China was the inseparability of religion and art, and of religion and the political structure. This is abundantly evident in the exhibition.” [27]

Works Cited

Act I: Objects

[1] This description is from the home page of the exhibition at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. See http://www.asianart.com/exhibitions/bowers/index.html

[2] Associated Press, “Historic agreement brings Tibetan treasures to U.S.,” CNN Online, October 16, 2003. http://www.cnn.com/2003/TRAVEL/DESTINATIONS/10/12/tibetan.treasures.ap/

[3] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html

[4] David Pagel, “Tibet’s treasures seen on a human scale; An exhibition of jewelry, sculptures and everyday artifacts in Santa Ana is unpretentious yet impressive,” Los Angeles Times, October 31 2003. The article is accessible online through ProQuest.

[5] This description of one of the object’s in the museum and the two that follow it were used by the Houston Museum of Natural Science. See http://tibet.hmns.org/images/selections(t).pdf See also the home page of the exhibition at the Houston Museum of Natural Science: http://tibet.hmns.org/ The Houston Museum website includes downloadable images (under the heading “Press”) and all of the images that appear in Act I of this dialog are from this site. Also of interest is the descriptions of the Adult Education Programs offered by the museum in conjunction with the exhibition, especially the panel “Modern Tibet: The Legacy of the Past ad Challenges of the Future,” which included a discussion of Tibet’s contemporary political situation.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

Act II: Collisions

[8] This statement was made by Denis Cusack, “a board member of the Tibet Justice Center, which advocates an independent Tibet.” See Associated Press, “Historic agreement brings Tibetan treasures to U.S.,” CNN Online, October 16, 2003. http://www.cnn.com/2003/TRAVEL/DESTINATIONS/10/12/tibetan.treasures.ap/

[9] Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2 The individual quoted in this citation is Rick Weinberg, the director of public relations and marketing for the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana.

[10] “Bowers Tibet Exhibit Update: Issues Raised by the Southern California Tibetan Community and Tibet Supporters with Suggested Corrective Action by Bowers Museum of Cultural Art,” Los Angeles Friends of Tibet website, http://www.latibet.org/Bowers/bowers-issue.htm The image of the monk creating a sand mandala is from http://www.artnetwork.com/mandala/gallery.html This sand mandala was made for the California Museum of Art in 2001.

[11] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html Peter C. Keller is the president of the Bowers Museum.

[12] “Tibetan Rights Group Calls Bowers Museum Exhibit Stolen Art,” Tibet Justice Center Website, http://www.tibetjustice.org/press/03.10.13-bowers.html

[13] Lisa Tsering, “Activists Blast SF Museum’s Exhibit of Tibetan Art,” Asian-American Village News, http://www.imdiversity.com/Villages/Asian/arts_culture_media/pns_tibet_art_0605.asp

[14] Mark Vallen, “Stolen Art & Cultural Destruction,” Mark Vallen’s “Art for a Change” Weblog, http://www.art-for-a-change.com/blog/2005/04/stolen-art-cultural-destruction.html This is a weblog by a working artist. He discusses the Tibet exhibit and compares it to an exhibition of Iraqi artifacts called The Gold of Nimrud: Treasures of Ancient Iraq.

[15] Sue Morrow Flanagan, “Treasures in cultural crossfire,” Financial Times (London), April 4, 2005. Online at http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2005&m=4&p=4_4

[16] Ibid. Lhedon Tethong is executive director of Students for a Free Tibet.

[17] Ibid.

Act III: Distances

[18] Jennie Klein, “Being Mindful: West Coast Reflections on Buddhism and Art,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 27.1 (2005), pp. 82-90. Available online at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/performing_arts_journal/v027/27.1klein.html [Access may be limited].

[19] David Pagel, “Tibet’s treasures seen on a human scale; An exhibition of jewelry, sculptures and everyday artifacts in Santa Ana is unpretentious yet impressive,” Los Angeles Times, October 31 2003. The article is accessible online through ProQuest.

[20] Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2 The individual quoted is Tseten Phanucharas, one of the many people who protested the exhibition at the Bowers Museum.

[21] Gary Gach, “Note on San Francisco Venue,” http://www.asianart.com/exhibitions/bowers/note.html From the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco website.

[22] This comment was made by Topden Tsering, head of the Bay Area branch of the Tibetan Youth Congress. See Lisa Tsering, “Activists Blast SF Museum’s Exhibit of Tibetan Art,” Asian-American Village News, http://www.imdiversity.com/Villages/Asian/arts_culture_media/pns_tibet_art_0605.asp

[23] This comment was made by Rick Weinberg, the director of public relations and marketing for the Bowers Museum, Santa Ana. Daniel Yi, “Tibetan Exhibit is More Political Artifice than Art, Protesters Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2004. Available online through the website of the Canada Tibet Committee: http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2004&m=2&p=22_2

[24] Sue Morrow Flanagan, “Treasures in cultural crossfire,” Financial Times (London), April 4, 2005. Online at http://www.tibet.ca/en/newsroom/wtn/archive/old?y=2005&m=4&p=4_4

[25] “Tibet Becomes Part of China 700 Years Ago,” Peoples Daily. http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200105/14/eng20010514_69926.html The “relics” mentioned in this quotation include many that were on display in the Tibet: Treasures from the Roof of the World Exhibit. The author of this article, however, is referring to an exhibition put on at the Sagya Monastery in Lhasa.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Robert L. Pincus, “Bowers Museum scores rare ‘Treasures’,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, August 8, 2004. http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040808/news_1a8tibet.html

Its Life as an Artifact ~1908-2008

Its Life as an Artifact ~1908-2008

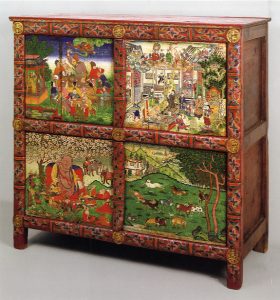

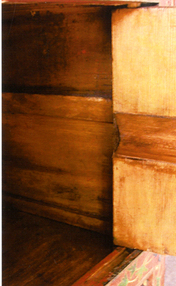

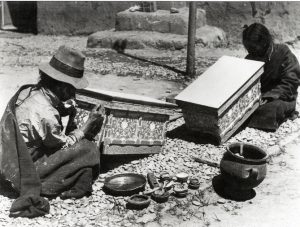

Wood for construction purposes was available in the highlands of the central Tibetan plateau (where the largest urban hubs, Lhasa and Shigatse, are located), but this was a local softwood referred to as chapa; it was the timber of the spruce, pine and fir trees found in the forests of the eastern province of Kham that was prized by furniture makers. [6] Most likely constructed from one of these quality hardwoods, the Newark chagam displays the frame-and-panel style typical of Tibetan cabinets: doors and – sometimes – sides are composed of discrete panels set into an enframing structure, creating a visual effect not unlike that of a coffered surface. Here, each of the four doors is hinged with wooden dowels, or connective pegs (above), which attach the top and bottom of the door to its frame, allowing it to swing open and shut. The doors were originally fastened around the central decorative brass loop by a metal plate (of the sort seen at right) and a lock, both now presumably lost. [7]

Wood for construction purposes was available in the highlands of the central Tibetan plateau (where the largest urban hubs, Lhasa and Shigatse, are located), but this was a local softwood referred to as chapa; it was the timber of the spruce, pine and fir trees found in the forests of the eastern province of Kham that was prized by furniture makers. [6] Most likely constructed from one of these quality hardwoods, the Newark chagam displays the frame-and-panel style typical of Tibetan cabinets: doors and – sometimes – sides are composed of discrete panels set into an enframing structure, creating a visual effect not unlike that of a coffered surface. Here, each of the four doors is hinged with wooden dowels, or connective pegs (above), which attach the top and bottom of the door to its frame, allowing it to swing open and shut. The doors were originally fastened around the central decorative brass loop by a metal plate (of the sort seen at right) and a lock, both now presumably lost. [7]

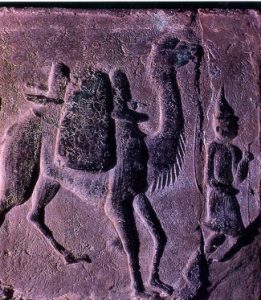

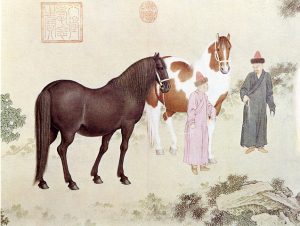

The scenes, beginning clockwise from the upper left, have been identified as: Central Asians and Qing officials gambling and eating in the garden of a Lhasa nobleman (left); a Chinese gentleman hosting a party at which a magician is conjuring up coins and celestial beings; the Chinese patron and sage Hva-shang; and, lastly, frolicking horses in a Tibetan landscape. [17] The first of these is notable chiefly for the racialization of its figures: Central Asia, the region once known as Turkestan and today the Chinese province of

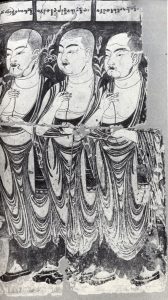

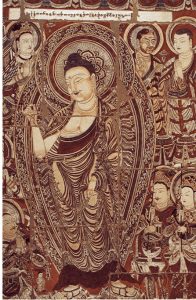

The scenes, beginning clockwise from the upper left, have been identified as: Central Asians and Qing officials gambling and eating in the garden of a Lhasa nobleman (left); a Chinese gentleman hosting a party at which a magician is conjuring up coins and celestial beings; the Chinese patron and sage Hva-shang; and, lastly, frolicking horses in a Tibetan landscape. [17] The first of these is notable chiefly for the racialization of its figures: Central Asia, the region once known as Turkestan and today the Chinese province of  Continuing their advance along the corridor they next brought to light from beneath the sand fifteen giant-sized paintings of Buddhas of different periods. Other figures, shown kneeling before the Buddhas offering gifts [right], were of particular interest to von Le Coq since they depicted individuals of different nationalities. They included Indian princes, Brahmins, Persians – and one puzzling character with red hair, blue eyes and distinctly European features. [22]

Continuing their advance along the corridor they next brought to light from beneath the sand fifteen giant-sized paintings of Buddhas of different periods. Other figures, shown kneeling before the Buddhas offering gifts [right], were of particular interest to von Le Coq since they depicted individuals of different nationalities. They included Indian princes, Brahmins, Persians – and one puzzling character with red hair, blue eyes and distinctly European features. [22]

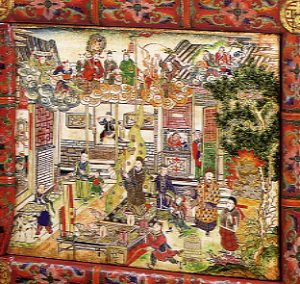

The second panel (left) marks a departure from its brethren: its subject matter and style suggest that the artist was looking directly to Chinese woodblock prints for inspiration, and may indeed have been a replacement for an original door. [28] Similar scenes can be found in that genre commonly referred to as New Year pictures, or nian hua (年画), the earliest examples of which may be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (841 – 256 BCE), when designs of animals like tigers were pasted onto the gates of domiciles as apotropaic talismans during the Lunar New Year. Two manuals attributed to the Song Dynasty statesman, scientist and polymath

The second panel (left) marks a departure from its brethren: its subject matter and style suggest that the artist was looking directly to Chinese woodblock prints for inspiration, and may indeed have been a replacement for an original door. [28] Similar scenes can be found in that genre commonly referred to as New Year pictures, or nian hua (年画), the earliest examples of which may be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (841 – 256 BCE), when designs of animals like tigers were pasted onto the gates of domiciles as apotropaic talismans during the Lunar New Year. Two manuals attributed to the Song Dynasty statesman, scientist and polymath

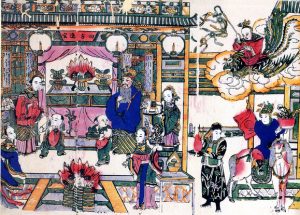

The bottom pair of panels likewise present interesting studies. The one on the left portrays Hva Shang – whose name is a transliteration of the Chinese term for a monk, he-shang (和尚) – considered the Chinese patron of the 16 Arhats. Historical accounts tell us that he was sent by Tang emperor to extend an invitation to the Buddha Shakyamuni, but, the latter having already passed on, addressed himself to the arhats instead. Hva Shang is usually portrayed as a bald, portly figure, seated beneath or beside a flowering tree with a rosary in his right hand and an offering to the arhats in the left, and frequently surrounded by cavorting children and one or more Buddhist deities. [31]

The bottom pair of panels likewise present interesting studies. The one on the left portrays Hva Shang – whose name is a transliteration of the Chinese term for a monk, he-shang (和尚) – considered the Chinese patron of the 16 Arhats. Historical accounts tell us that he was sent by Tang emperor to extend an invitation to the Buddha Shakyamuni, but, the latter having already passed on, addressed himself to the arhats instead. Hva Shang is usually portrayed as a bald, portly figure, seated beneath or beside a flowering tree with a rosary in his right hand and an offering to the arhats in the left, and frequently surrounded by cavorting children and one or more Buddhist deities. [31]