-

Thus have I heard what this Parinirvana Statue tells us in March 2008.

by Hojeong Choe

by Hojeong Choe

Parinirvana, Gilt bronze, pigment, lacquer, H. 15.3, L. 22.0, W. 8.0 (cm),

Gift of William B. Whitney, American Museum of Natural History (Cat. no. 70.0/6980)

The reclining figure in the center is the historical founder of Buddhism, the Buddha Shakyamuni. He is leaning on his right side flanked by his attendant Ananda who is kneeling at the Buddha’s head. The Ananda figure is on a cloud-like platform rising from the left front corner of the bed throne. The same kind of platform also rises from its right front corner. This might have been the place where Kashapa, the oldest disciple of the Buddha, was kneeling at the Buddha’s feet.

This figure is associated with story of parinirvana of the Buddha, the last phase of the life story of the Buddha Shakyamuni. His sermon and the circumstances of this story are depicted in the Buddhist scripture called the Mahaparinirvana Sutra in Sanskrit, which is also called Mahaparinibbana Sutta in the Pali language. Mahaparinirvana literally means ‘great (maha) complete (pari) extinguishing (nirvana).’ This last event of Shakyamuni’s life story, Mahaparinirvana, takes place at the town called Kushinagar, located in the northeastern part of India in the region of Uttar Pradesh. There the Buddha passed into nirvana and his body was cremated.

This parinirvana scene has been the most popular theme to be depicted in various genres of the Buddhist art such as stone relief, wall painting, sculpture, hanging scroll, etc. in different regions of the world: Ajanta, Gandhara, Kushinagar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Sichuan, Tibet, Dunhuang, Korea, Japan as well as in New York. [Nirvana Art in Asia]

According to Akira Miyaji, an art historian whose special field is Indian art history, particularly Maitreya and Nirvana iconography in Gandharan art, depiction of nirvana scenes were generally horizontal and had an element of storytelling in Gandhara and Mathura. This kind of storytelling enabled ‘visual pilgrimage’ according to Miyaji. He also asserts that the mortuary customs of both Rome and India had influenced depiction of the last moment of the Buddha’s life story. This nirvana scene, however, started to be depicted vertically in Sarnath and no longer had a storytelling element. It was because the depiction of nirvana and enlightenment of the Buddha had more importance than other scenes of the Buddha’s life story by then. After Pala period, the time when Buddhism and Buddhist art declined in India, this nirvana scene also did not develop. However, outside of India, nirvana statue alone was very popular and there are many nirvana statues remaining in Sri Lanka, Thailand, etc.

While many other nirvana statues are on a large scale, this statue at the American Museum of Natural History (hereafter AMNH) is on a small scale. It might have been used as portable shrine. This statue might have been enshrined with his head pointing north as the Buddha Shakyamuni put his head toward north facing west according to the Buddhist scripture. This object is likely to have been enshrined at the home altar of ordinary people rather than court. The way that patterns of the bed throne are articulated shows that the statue is not high quality object.

The inscriptions support this hypothesis as well. The inscriptions are engraved on three sides along the small panels above the lotus petals. At first sight, these letters seem to be derived from 11th century Nepalese script among the various versions of Sanskrit letters. However, most of these letters are poorly written and do not indicate any mantra, names of donors or artisans.

Front/Back/Left/Right Inscriptions (Clockwise from Top Left to Bottom Left)

The front inscription between poorly inscribed floral patterns can be Romanized as ‘so nah ma – -.’ The inscriptions on back, left and right sides are as follow: ‘aum ra/ya/pa jha – – -’(back); ‘- ra/ya/pa jha – te ra’(left); ‘- – dr te ya/pa – -’(right) [Thanks to Prof. Somdev Vasudeva and Victor for their advice on inscription decipherment and Romanization.]

With the information from AMNH that this object is Tibetan piece, I have tried to decipher the inscriptions with Lantsa (Ranjhana) scripts at first. However, the letters were not correspondent to any of Lantsa scripts. This statue seems to be casted in China by the artist who does not read and know Sanskrit. If it were made by a court artisan, the inscriptions are likely to be written in correct Sanskrit. However, in this case, the inscription does not mean anything and is incorrect. To locate this statue on the map, it might have been made in main land China. Therefore, this statue would belong to Sino-Tibetan art, instead of Tibetan since it does not show orthodox Chinese or Tibetan element, but mixture of several different traditions. It seems to be appropriate to align this object on timeline between 17-19th century. And the color of lacquer shows Qing Dynasty taste.

The pattern of leaves which seem like sal tree leaves shows that artisan of the object knew and expressed the element of

The pattern of leaves which seem like sal tree leaves shows that artisan of the object knew and expressed the element of Indian Buddhist art tradition.

At the same time, the artisan used the Chinese traditional pattern of bat when filling the surface of the bed throne. The Chinese word for bat is fu. Fu is a homophone for happiness. Around 17th century, bats began to feature in auspicious pictures as a symbol of happiness. By the middle and late Qing Dynasty, auspicious bat motifs had had become widely used on architecture, textiles, embroidery, paintings, chinaware, furniture, and brick and stone carvings. This bat pattern also implies the chronological clue.

Then why was this object categorized as Tibetan object? The late Mr. William B. Whitney, a lawyer, has donated his collection to American Museum of Natural History in 1937 and it was named ‘Tibetan Lamaist Collection.’ His collection has been introduced in several books authored by Antoinette Gordon. According to the curator at AMNH, Mr. Whitney purchased Tibetan art objects via dealers in New York as well as from Art Exhibition at Macy’s. Among 910 objects donated to AMNH by Mr. Whitney in 1937, there are two more parinirvana statues. This object was understood not by its original context, but by the context of the contemporary collection.

The present condition of this object seems to be well reserving the original state. It consists of two parts: one is the bed throne including cloud-like platforms attached to it and the other one is the reclining Buddha figure. The figure has metal pins attached on the side that meets the bed frame. The pins were inserted into the bed frame and bent to secure the statue. On the other hand, there are several things missing and changed. From the uncomfortable position of the Buddha’s head suggests that there has been headrest or pillow under his right hand. As mentioned in the first paragraph, the cloud-like platform on the right side must have been a seat of Kashapa. Lacquer pigments have flaked off and the left rear leg had broken off and was reattached later. The material of the bed throne leg is iron, which cannot be cut or broken easily. It is possible that this object was buried underground and there had been huge exterior pressure by construction devices right before excavation.

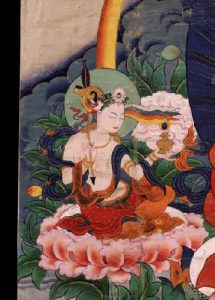

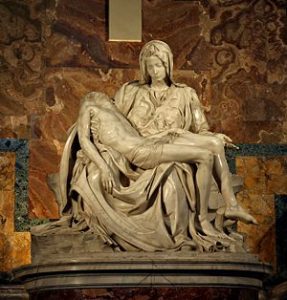

In the context of the depiction of death of the religious founder’s can be comparable to Pieta by Michelangelo. This reclining posture appears in the European arts as well such as Etruscan Sarcophagus at Villa Giulia.

The last but not least thing that makes this object rare and interesting is the facial expression of the reclining Buddha. The smiling face does not seem like ordinary Buddha statues, but more like Milarepa. Further study of the route how the late Mr. Whitney purchased this object and the scrutiny of the other objects, which were purchased or excavated along with this object would enable to identify this object much clearer.

This article is hypothetical based on the knowledge and information currently available.

The comments on the time period, artisan, nationality, inscription decipherment, etc. are welcome.

Last update: 2008-03-07