Passionate Urban Economics

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier

By Edward Glaeser (Penguin Group Inc.)

“Cities enable the collaboration that makes humanity shine most brightly. Because humans learn so much from other humans, we learn more when there are more people around us.”

— Glaeser, Triumph of the City

Not only do humans make cities, but also, Harvard economist Glaeser argues, cities make us more human. Cities triumph because of their ability to enhance our greatest strength—our ability to think and learn. This is because we learn most fully when we interact face-to-face, and communication technology has not yet been able to replicate this.

As Glaeser points out, cities have been the source of our progress throughout time and space. 2,500 years ago, Athens attracted many of the brightest minds in Asia Minor, producing much of the Western canon of philosophy, theatre, and other arts. Glaeser provides many interesting examples of how cities allowed humankind to make great leaps forward. In each case, he explains how urban proximity was fundamental to innovation.

The book clearly reveals Glaeser’s sincere passion for cities, making it a pleasurable read. The tone of the book is much like The Economy of Cities by Jane Jacobs (1969) and The Wealth of Cities by John Norquist (1998) that shed light on the under-appreciated benefits of cities.

The book’s main virtue is its big-picture evaluation of cities. Despite being loaded with examples, it gives a clear overall sense of how we can make cities better, and more importantly, how cities make us better.

– Kyle M. Kirschling

Roadblocks Remain for Regional Equity

This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity are Reshaping Metropolitan America

This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity are Reshaping Metropolitan America

By Manuel Pastor Jr., Chris Benner, and Martha Matsuoka (Cornel University Press)

In their 2009 work, Pastor, Benner and Matsuoka explore the theoretical framework of the regional equity perspective. The authors provide a thorough synopsis of social movement regionalism, which identifies the metropolitan region as not only the scale of problems and potential solutions, but also the scale at which to create a social movement for change.

A main criticism of the book is that the authors oversimplify the concept of regional equity in their failure to clearly differentiate it from social equity, which leaves the reader with an incomplete picture of the transportation equity conundrum. Although it is clear that Pastor et al. are social equity advocates at heart, their conclusions fail to consider a sustainable transportation viewpoint to help untangle the issues of regional and social equity.

The multi-faceted transportation agenda must address regional and social inequity. However, these objectives are not necessarily mutually supportive. The authors point to examples of investment in commuter rail, endorsed by both suburbanites and central city residents, as regional equity success stories that also promote social equity. While commuter rail does facilitate reverse commuting, which can have social equity benefits, from a social equity perspective, the limited funding available for transit investments would be better targeted to improving accessibility within the central city.

Although the book does not discuss the anticipated federal transportation re-authorization bill, it concludes by asserting that a national movement built around regional equity can, will, and must emerge as a “transformative force for a better America.” It remains unclear whether the envisioned “better America” will be able to pride itself on true social equity or merely the socially inequitable status quo couched in achievements of regional equity.

– Maxwell Sokol

Beyond Alternative Fuel Solutions

Two Billion Cars: Driving Towards Sustainability

By Daniel Sperling and Deborah Gordon

(Oxford University Press)

Transportation policy will arguably play the most important role in mitigating the inevitable effects of climate change. Worldwide, there are one billion cars on the road—a number that could double in the next 20 years.

More cars on the road and more drivers produces more congestion and pollution, more strains on quickly depleting and environmentally sensitive resources, longer travel distances, and inequitable effects on others. As countries like China and India turn to car culture, there is still opportunity to revamp the entire way we move around.

Daniel Sperling and Deborah Gordon, the authors of Two Billion Cars: Driving Towards Sustainability, see this as an opportunity. Both transportation policy experts, Sperling and Gordon write of America’s reliance on the car, and what is needed to instigate a move away from car culture. Their argument covers three main points: innovation in alternative fuel sources, development of an efficient car, and progress in consumer behavior. They apply these not only in the United States, but most pressingly, in rapidly developing China.

The authors believe that by 2050, massive shifts will be underway in alternative fuel, efficient vehicles, and consumer behavior. Improvements and changes in fuel source and efficiency are required to reduce projected climate change, but this alone will not be enough. For both the short- and long-term, policies must shift travel behavior, as the effects will be more effective and lasting. Technological solutions are also needed for the short term. Mobility is now cheap and is seen as a “right” in the US, but it obviously has major costs. Ultimately, the marginal cost of a car trip is less than the marginal cost of public transportation – this must change if there is to be any global transformation.

– Mia Pears

Cold Future Ahead

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future

By Laurence C. Smith (Dutton)

An exploded population leveling off around 9.3 billion, dwindling sources of fresh water and fossil fuels, rising global sea level, mega storms, and warmer global temperatures are just a few of the changes we can look forward to in the next half-century. In The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future, Laurence C. Smith thoroughly surveys these “hot” topics on the global agenda.

A professor of geography and earth and space sciences at UCLA, Smith also took the time to travel the world documenting firsthand accounts of climate change on the atmosphere and civilizations. He provides an account of the current state of the world’s environment and combines the current trends to project a portrait of what the future may look like. It is clear to the reader that the future is bleak—the clock is ticking and we need to take action! Smith’s forecasts revolve around four forces that he posits will shape the future of the world: demographics, natural resource demand, climate change, and globalization.

In the end, Smith argues that much of our future lies to the north, where economic opportunities and stability should stand out. Cities like Toronto and Stockholm, he says, will continue to grow. Less so in the high Arctic, which will still be foreboding. “Its prime socioeconomic role in the twenty-first century will not be homestead haven,” Smith writes, “but economic engine, shoveling gas, oil, minerals, and fish into the gaping global maw.” Nothing is inevitable, though, as he makes clear. The actions we take in the next few decades could reshape the world of 2050 that Smith has laid out. We can either grab up real estate in Oslo and Reykjavik, take one last long look at the Arctic, or we can start to plot a new way forward.

– Dan Rosen & Joyce Tam

Paralyzed by Property Rights

Gridlock Economy: How Too Much Ownership Wrecks Markets, Stops Innovation, and Costs Lives

By Michael Heller (Basic Books)

“The cold war is over, most socialist states have disappeared, intense state regulation of resources has dropped from favor, and privatization has accelerated.”

– Michael Heller, Gridlock Economy

A study released by the American Institute of Biological Sciences in February has announced that, worldwide, oysters no longer play a significant role in their ecosystems. The usual culprits are to blame: overexploitation, degradation of habitat, invasion of non-native species. A commonly held resource that supported life for millennia has now become a tragedy of the commons.

This is bad news for lots of reasons: epicures can no longer slurp freely, oystermen will go out of business, and oyster-beds will cease to filter water, reduce algae blooms, buffer erosion, and support coastal biodiversity. But it’s especially bad news for the handy symmetries of Michael Heller’s book Gridlock Economy, in which oyster conservation is offered as a kind of paragon of public-private cooperative commons management. Tragedies of the commons, according to Garret Hardin, occur when a resource is available for use by all yet no one in particular feels a responsibility to preserve it.

Heller builds on Hardin’s concept to suggest that resource use occurs along a spectrum, with overuse on one side and underuse—the “anticommons”—on the other. An anticommons is a resource or a good that is split so many ways that it is unusable.

Heller believes that “commons and anticommons tragedies mirror each other, so solutions for one may inform the other.” If this is the case, our anticommons may be in trouble. If the oyster’s expense failed to save it, perhaps market-based solutions to problems of the commons are not as robust as we had hoped.

Yet overall, Heller’s argument about the patchwork of ownership that builds optimum resource management makes sense. The more we shift toward public-private partnerships in transportation policies and across government, the truer this will become, and the more useful the “gridlock”concept.

– Greta Byrum

All reviews edited by Sara Beth Rosenberg

This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity are Reshaping Metropolitan America

This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity are Reshaping Metropolitan America

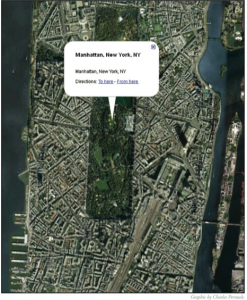

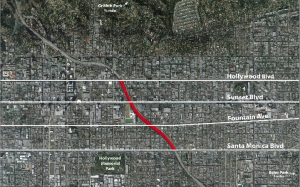

Both New York City’s recently opened High Line park, and Los Angeles’ answer to it, the Hollywood Freeway Central Park, are reminiscent of the City Beautiful movement – the turn-of-the- 20th century planning approach responsible for such enduring landscapes as Central Park and Prospect Park. A century later, cities are still building parks that reclaim and readapt space in unconventional ways. Today, new parks not only serve as destination points for residents and visitors, but they act as tools for increasing the city’s global profile.

Both New York City’s recently opened High Line park, and Los Angeles’ answer to it, the Hollywood Freeway Central Park, are reminiscent of the City Beautiful movement – the turn-of-the- 20th century planning approach responsible for such enduring landscapes as Central Park and Prospect Park. A century later, cities are still building parks that reclaim and readapt space in unconventional ways. Today, new parks not only serve as destination points for residents and visitors, but they act as tools for increasing the city’s global profile.

Once a thriving Brooklyn neighborhood and famous seaside destination, Coney Island has suffered economic decline following

Once a thriving Brooklyn neighborhood and famous seaside destination, Coney Island has suffered economic decline following