The cinema of China has a rich and troubled history that intrigued me even before I studied abroad in Beijing. In the past, most Chinese movies that have made it to the states have been lushly illustrated martial arts numbers (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero) or quirky Jackie Chan comedies. However, a number of lesser-known Chinese films have been shown in international film festivals and at arthouse theaters since the 1980s, and they offer much more compelling portrayals of Chinese people and events throughout China’s turbulent modern history.

During my semester abroad, I interned at a Chinese film distribution company and had the opportunity to learn more about Chinese cinema and issues of media censorship. Chinese cinema is often divided into different “generations” chronologically. Many of the extremely diverse films that have been made since the twentieth century have explored and captured the sentiments left by cataclysmic events in China’s history, particularly the Cultural Revolution. Their political overtones have led them to be banned by the Chinese government, even to this day.

Besides meeting locals and exploring hutongs, it’s also entirely possible to learn about China within the comforts of your own bed with a bag of popcorn and some juice. From the thick rich depths of Chinese cinematic history I’ve dredged up a list of Chinese movies that are not only great movies in and of themselves, but also formative films that capture pieces of China’s modern history:

Yellow Earth (1984) was one of the first films made after the Cultural Revolution and is considered the signature piece of the Fifth Generation of filmmakers. It was directed by Chen Kaige, and the cinematography is by Zhang Yimou—both of whom would become prominent filmmakers in their own right. The vast, parched landscape of Shaanxi province is the backdrop for the journey of a Communist soldier through impoverished villages searching for rural folksongs to turn into propaganda for the Communist army.

Farewell My Concubine (1993) is the only Chinese-language film to have won the Cannes Palme d’Or. Directed by Chen Kaige, it explores the relationship between two men in a Peking opera troupe and a woman who comes between them, and how the effects of China’s mid-20th-century political turmoil permeates their lives.

Raise the Red Lantern (1991), directed by Zhang Yimou, is one of the most iconic movies of Chinese cinema. Noted for its opulent visuals and sumptuous photography, it tells the story of a nineteen-year-old girl who becomes the new concubine of a wealthy lord, and the tension and intrigue that arises among her and the lord’s three other wives. The film was interpreted as a metaphor for the fragmented civil society of post-Cultural Revolution China and was banned in China for a time.

The Last Emperor (1987), directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, is a biopic about the life of Puyi, the last emperor of China, from his early royal upbringing to the foundation of the early Chinese Republic, to his exile and eventual return. It won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director in 1987

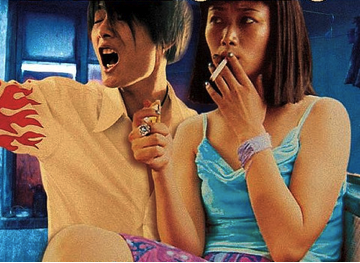

Unknown Pleasures (2002) is a film about three aimless, disaffected youths growing up in China as part of the new “Birth Control” generation, fed on a steady diet of Western and Chinese popular culture. It is directed by Jia Zhangke, a Sixth Generation filmmaker widely lauded as perhaps “the most important filmmaker working in the world today.”