Between Propaganda and Public Relations: An Analysis of Bashar al-Assad’s Digital Communications Campaign

Monday, March 9th, 2015

While autocrats are known for imposing strict regulations on speech, the intrinsic openness of digital communications sets up an interesting challenge. Bashar al-Assad has built an online campaign that is highly communicative, seemingly transparent, and spans multiple social media accounts, while attempting to transmit a rigid agenda. In the digital era, political communications lie increasingly on a nuanced spectrum between the fields of journalism, public relations, advertising, and propaganda. On this spectrum, Assad has built a pervasive and multifaceted communications campaign over the course of the Syrian crisis by leveraging both official and non-official media channels. The regime’s ability to effectively target strategic audiences and opinion leaders by way of social media is notable, though its success in swaying opinion in its favor is dubious.

The Assads began dabbling in contracts with public relations firms well before the crisis began in 2011. According to the New York Times, the campaign to portray the ruling family as a symbol of a modern, open, westernized Syria began in 2006 when Asma al-Assad began negotiations with Bell Pottinger in London. Subsequently, the regime formed a contract with an American public relations firm, Brown Lloyd JamesWorldwide LTD,between 29 July 2010 and 30 April 2011. The contract resulted in the publication in Vogue’s February 2011 issue of an article praising Asma al-Assad, notably describing her as a “rose in the desert.”

The household is run on wildly democratic principles. “We all vote on what we want, and where,” she says. “The chandelier over the dining table is made of cut-up comic books. They outvoted us three to two on that.”

The article appeared in the magazine about a month before the Assad regime began its brutal crackdown on demonstrators; the indignant public reaction eventually led to its withdrawal. Though the regime is not currently in contract with any American PR firms according to official records disclosed by FARA (Foreign Agents Registration Act), these early relationships indicate the careful attention it invests in strategic communications.

The communications system of the Assad regime is a complex network, which consists of several components. Assad’s presence on social networks includes accounts on YouTube (Syrian Presidency), Twitter (@Presidency_Sy), and Instagram (@SyrianPresidency). In the media, pro-Assad communications have a presence in the official press by way of official interviews as well as in underground blogs and websites, such as InfoSyrie.fr and VoltaireNet.org in France.

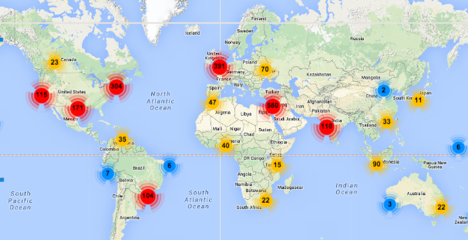

Assad’s Twitter following is geographically broad and socially diverse with 13,900 followers as of October 2014. Some of the most frequently appearing words in a word cloud of the regime’s followers’ Twitter biographies indicate they are interested in the account for business purposes with a visible portion self-identifying as journalists, featuring words such as “media,” “foreign policy,” “freelance journalist,” “international relations,” “bureau chief,” or “news editor” in their Twitter biographies. Through Twitter, Assad is able to establish a flow of direct communication with the international media.

- Global distribution of the regime’s Twitter followers based on a sample of 2,212, Followerwonk.com, 7 March 2015.

The geographic scope of the Assad regime on Twitter is vast, reaching across various continents, but is clustered around hubs of political influence. The areas with the most followers of the regime’s Twitter accountare in major urban centers, according to the most recent Followerwonk.com sample of over 2,000 followers drawn on 7 March 2015. There is also a horizontal distribution of followers corresponding to urban centers in the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East. There are an estimated 537 followers in Beirut and 693 in Damascus. The city with the greatest concentration of followers in the region is Aleppo, with an estimated 1,209 followers (8 percent of the sample); roughly on par with London, which has an estimated 1,060 followers. The regime’s Twitter account therefore mainly affects the urban centers of major players in the Syrian conflict, including Syria itself, neighboring Lebanon, which has links with armed groups fighting in Syria, as well as the United Kingdom, other European hubs, and the U.S. The largest concentrations of followers are in the U.S., with an estimated 4,171 followers, making up 27 percent of the sample, and in the immediate geographic vicinity of Syria, an estimated 4,100 followers making up 26 percent of the sample,. However, when taking into account the number of active Internet users in the U.S. and the Middle East, the percentage following Assad in the immediate geographic region is at least three times the percentage in the U.S.

- Geographic distribution of the regime’s Twitter followers in the Mediterranean region, Followerwonk.com, 7 March 2015.

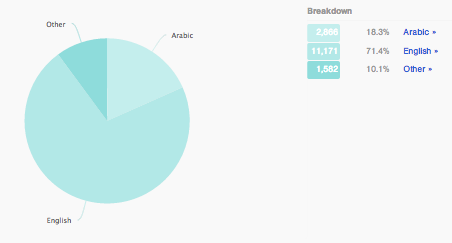

It is interesting to note that there is very little interest on Twitter about the Assad regime in the countries of the Arab Spring—Libya, Algeria, and Tunisia—compared to the level of interest the Twitter account attracts globally, especially in Europe and the U.S. While 81.3 percent of Assad’s followers reported English as their official language in a Followerwonk.com report of the @Presidency_Sy account in October 2014, a meager 9.7 percent chose Arabic, indicating that Assad’s primary public on Twitter is not local to the conflict. Today, the margin has shrunk to 71.4 percent choosing English, and 18.3 percent of followers choosing Arabic. [1]

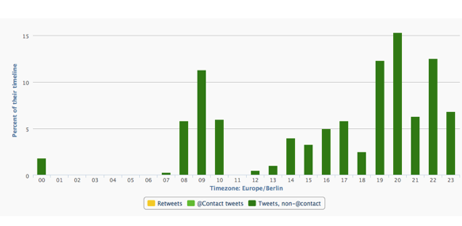

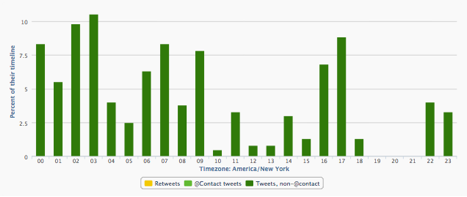

In October of 2013, the regime’s use of Twitter revealed a fairly basic level of technical expertise. The regime’s social networking began at 8 a.m. local time, with a gradually increasing volume of tweets until noon when there was a sudden lunch break. Tweeting then picked up again and lasted until 1 a.m., followed by a total break overnight. We can therefore assume that there was one or several individuals managing the regime’s Twitter presence manually. Due to the heavily international following receiving these tweets in real time, posting according to the Syrian time zone was a significant inefficiency in the regime’s digital strategy.

- Average distribution of tweets produced throughout the course of a day by the Assad regime, n=400 of the account’s most recent actions, Followerwonk.com, 23 October 2013.

- Average distribution of tweets produced throughout the course of a day by the Assad regime, n=400 of the account’s most recent actions, Followerwonk.com, 7 March 2015.

Today, the Assad regime has become more active on Twitter around the clock. The only time of day in which there are no tweets on average is between 1 a.m. and 3 a.m. local time, suggesting the regime has expanded its digital team to work around the clock and possibly across countries.

The Assad regime continues to function unidirectionally on Twitter using an authoritarian approach: employing Twitter solely as a means of emitting desired information. The regime’s posts are static and do not take advantage of the interactive capabilities of Twitter to retweet, follow, or direct messages at other users.

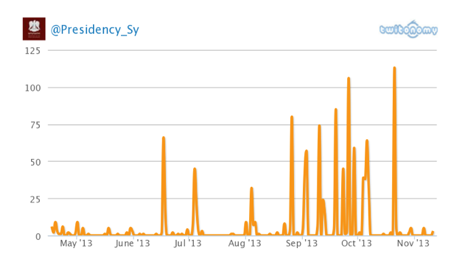

The regime’s peak activity on Twitter is strategically patterned—bursts of tweets occur in response to media crises rehashing content from Assad’s interviews with the international press.

- The distribution of tweets by the Assad regime’s @Presidency_SY account from May to November 2013, Twitonomy.com, 11 November 2013.

The regime followed this specific procedure in reaction to the official statement by the United States on 13 June 2013 denouncing Syria’s use of chemical weapons against opposition forces. The same day, the United Nations announced the death of almost 93,000 individuals in the conflict up to that point. Four days after this concentration of negative press, there was an unprecedented burst of tweets from the regime’s account. Tweets suddenly soared from fewer than five per day to over 60.

Similarly, on 21 August 2013, the opposition accused the regime of using chemical weapons and killing numerous civilians by surprise during the night. Subsequently, on 26 August 2013, @Presidency_Sypublished a series of 80 tweets incorporating excerpts from an interview of Assad with the Russian daily newspaper, Izvestia. After discussions about the U.S. intervention in Syria began on 27 August 2013, the Twitter account was even more reactive with the publication of excerpts from several interviews: an interview with Le Figaro on 3 September, an interview with ABC on 10 September, and an interview with Fox News on 19 September.

Thus, there appears to be a strong correlation between media crises involving the Syrian regime and the activity of the regime’s Twitter account. This strong reaction via social media serves to amplify Assad’s responses to these crises and rebuttals to accusations by pushing content from official interviews to the press.

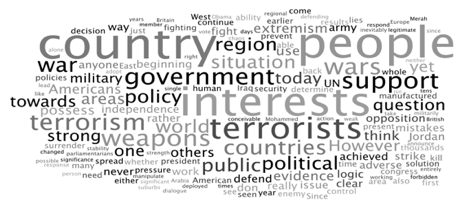

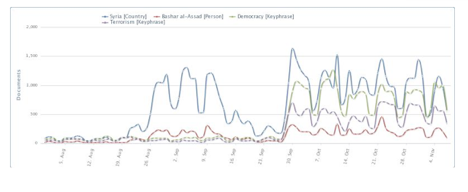

Based on an analysis of recurring language in official interviews, Assad consistently constructs his arguments on three pillars which have begun influencing the narrative of the mainstream media: (1) the use of democratic language, which gives an appearance of legitimacy to the regime, (2) the claim that the regime stands in opposition to “terrorism,” a very powerful slogan in Western countries, especially following 11 September 2001, and (3) the refusal to take any responsibility or to give any credit to the sources attacking the regime. Words pertaining to these three themes have become increasingly correlated in the media’s coverage of the Syrian crisis.

- Evolution of the use of the keywords: “Syria,” “Bashar al-Assad,” “Democracy,” and “Terrorism” in the press from August 2013 to November 2013, Silobreaker.com, 11 November 2013.

While the global community discussed intervention in Syria at the end of August 2013, the word “Syria” peaked in the media at the same time. However, starting 1 October 2013, when weapons inspectors arrived in Damascus, the correlation between the use of the terms “democracy,” “terrorism,” “Bashar al-Assad,” and “Syria” became more direct, with all four terms oscillating together.

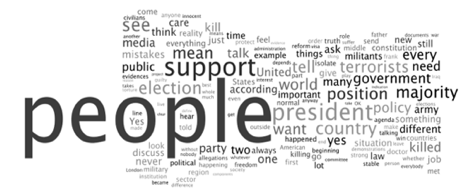

The language used in Assad’s December 2011 interview with ABC News and in his September 2013 interview with Le Figaro, reveals a similar focus on these themes. The frequency of the phrase “support of the people,” in Assad’s 2011 interview with Barbara Walters attempts to debunk his reputation as a despot by convincing listeners that his regime does indeed have widespread backing.

- Words appearing most frequently in Assad’s interview with Barbara Walters, graphic made with Wordle.net.

Assad used the same language when speaking to Le Figaro two years later: “I can continue to lead because of the strength of public support and the strength of the Syrian state.” Finally, by using meticulously rational language, Assad draws upon the reason of his listeners to refute “false allegations and distortion of reality.” In his interview with Le Figaro, Assad proclaims, “We will not contest rumours and dubious allegations; we will only discuss substantiated truths.” This consistency in messaging demonstrates that the regime’s communications strategy has remained unchanged since 2011.

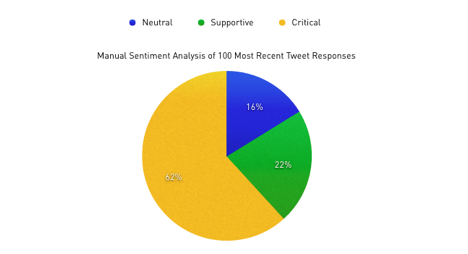

Despite Assad’s best efforts to inculcate his version of reality, public opinion does not seem to have altered in his favor. In fact, an analysis of a sample of 100 Twitter responses to the @Presidency_Sy Twitter account reveal distinct criticism rather than support or neutrality for the account’s claims. Indeed, 62 percent of the replies were critical, while 22 percent expressed support for the regime’s claims and 16 percent remained neutral. The journalists interacting with Assad on Twitter also appeared to be increasingly critical in subsequent articles rather than receptive to his tweets.

- Sentiment analysis of 100 most recent comments on the Assad regime’s Twitter posts, 28 February 2014.

In addition to a humanitarian crisis, Syria faces an information crisis where the boundaries between public relations, news, and social media are blurred. Digital communications are being used to support a dictatorship, contrasting the dominant narrative of social media revolutions sweeping the Middle East. Thus, we must consider digital communication channels and social networks as mere tools rather than bearers of inherent “democratic” power. These technologies have produced a new, more nuanced digital battlefield that adds complexity to international conflicts, but the effect of these techniques is not unidirectional. Digital information, seemingly open and not moderated, is often subject to underlying political and monetary influence.

[1] Note that Twitter only allows users to select from a few languages. Additionally, many Twitter users who tweet primarily in a foreign language may still have their official language set to English.