If I Were To Choose Between Being Born a Girl in India or China…

Monday, November 11th, 2013

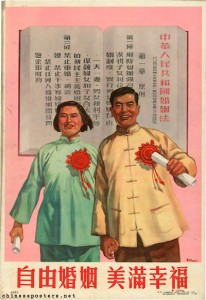

A 1953 Chinese propaganda poster reading: “Freedom in marriage;

happiness and good luck.” Photo credit: ChinesePosters.net

Within the past year, a number of shocking rape cases in India have surfaced. Ranging from pre-school girls to young adults, the callousness with which the perpetrators have treated their victims stands out. Recently, a four-year-old girl died of her rape injuries. A five-year-old girl remains in critical condition in hospital. In December 2012, in a widely publicized case, a twenty-something woman died in a hospital after a brutal gang rape left her all but eviscerated in New Delhi.

The picture that emerges from these incidents is of cultural attitudes that treat women as disposable objects. If you can grab it, then it is yours. Locked up in her house, she may be protected from strangers—but not from uncles and cousins. And should she stray outside, seemingly anyone can pounce on her.

No culture is immune to predatory behavior. Josef Fritz and Marc Dutroux operated in the heart of Europe. Still, the events in India are indicative of a culture still dealing with entrenched hostile attitudes towards women on an astounding scale. The callous treatment of girls and women in India is startling, not just in comparison with the West but also when paralleled to another Asian country not typically known as a female haven: China, inventor of the “Lotus feet” practice that left girls crippled for life.

In China, as is well-known, daughters are aborted at a high rate. The discrimination does not end there. Girls are more likely to not be properly cared for and have higher mortality rate than boys through their juvenile years.

Still, if I were to choose between being born a girl in India or China, my choice is clear. A girl born in India faces a much higher risk of malnutrition, illiteracy and child labor than a girl born in China. And very importantly, a girl born in India is unlikely to be able to choose when and whom to marry whereas those rights are hers with high certainty in China.

The Chinese girl will not marry before eighteen years of age, whereas there is a high probability the Indian girl will do so. In marriage—a marriage of her choice—the Chinese girl will likely fare better too. She is more likely to live separate from her in-laws and she is more likely to have a say in domestic matters.

What is it that makes for this misogyny on display in India—the world’s largest democracy, the cradle of non-violence, the home of Mahatma Gandhi and Indira, his daughter-in-law by adoption?

I believe this divergence of paths began in 1950 with the New China Family Law, also dubbed “women’s marriage law.” This law was modeled on Western Family Law. Importantly, it gave both of the intending spouses the right to marriage and the right to divorce, two rights previously vested with parents. The Nationalist Government had introduced a similar law in 1931 but it was poorly enforced. Before then, a man married when his father bought him a bride, and divorced when his father sold her. A woman married when sold by her parents. If divorced, she would be passed on to the secondary market of concubines and prostitutes.

While in principle both sons and daughters were owned, a man would eventually outlive his father and therefore would not serve his whole life as someone’s slave. Women were not so lucky. Moreover, note that in the above narrative that the girl is sold, she does not sell herself. Why does this matter? Well, it does in that the owner pockets the money. Parental consent (that is, arranged marriage) means that instead of the bride capturing her value on the marriage market, her owner does.

This may be the difference between the treatment of women in India and China. By virtue of the nature of the marriage market in these countries, in India, the girl is property; in China, the girl owns herself. Self-ownership is important. We can monetize it, but that would grossly underestimate the value of being your own person. Without it, there can be no respect for others; insincere subservience when needed, wanton brutality when possible, are substituted for civility. Entitlement and enslavement co-exist in an oppressive arrangement favoring fatalism over agency.

Individual consent in marriage is part of the Universal Declarations of Human Rights (Article 16). It is a concept introduced by the early Christian Church and has been a tenant of Western family law since the Church gained control over marriage sometime during the Middle Ages.

In the rest of the world, parents decided marriage and girls were routinely treated like chattel—bought and sold, used to settle debts or to curry favors (a practice somewhat moderated in Islam). Outside the West, East Asia stands out by its introduction of individual consent in marriage around 1950, while individual consent is still ignored in much of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

India practices personal law in matters of the family. Thus, in many parts of the Hindu and Muslim world today, though provisions exist for individual consent on the part women, cultural-specific applications of religious law often prevent women the freedom to decide marriage.

In parts of India, children used to be married off as young as five or six. Today, they are generally a bit older. Older marriage age means more resistance to arranged marriage. The insistence of parents to deny their grown children the right to decide marriage has resulted in a growing number of honor killings in India.

In 2010, Ms. Nirupama Pathak, a twenty-two year-old journalism student whose death is being investigated, is a recent poster child. She was secretly engaged to be married to a man of lower caste. Her parents caught wind of her plans and quickly made arrangements for a more “suitable” match. She resisted the arranged marriage but agreed to a visit with her natal family who found her dead in her bedroom. Her parents claimed it was suicide. In defense of their desire for an arranged marriage, her parents acknowledged that while the constitution allowed the kind of marriage she sought, “The Constitution had existed for only decades while Hindu religious beliefs dated back thousands of years.”

China certainly has a long history of oppressing women. But in 1950 it broke with tradition and gave women a very important right, and the difference in cultural attitudes towards women compared with India that we see today can be partially attributed to this shift in policy.

Author Biography

Dr. Lena Edlund is a tenured associate professor of economics at Columbia University. She holds a PhD in the field from Stockholm School of Economics. Dr. Edlund has written extensively on the role of gender in economics, and has been published in such publications as Economica, Population and Development Review, and Review of Economics and Statistics.