Toy Soldiers on Storify

Monthly Archives: November 2012

Peace & Quiet…Vets and Civilians Get Talking

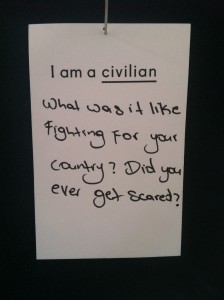

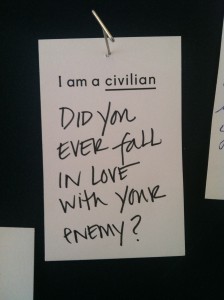

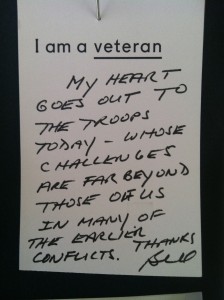

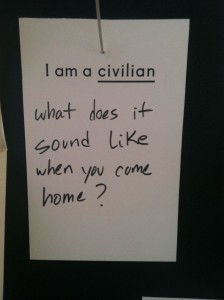

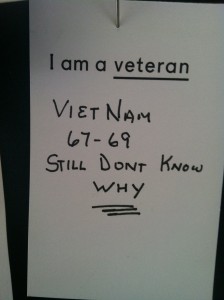

Here are some pics I snapped while visiting Peace & Quiet, the installation in Times Square that gave vets and civilians a “quiet space” to interact. This spare, bright little hut, created by the architecture firm Matter of Practice in collaboration with the Times Square Alliance, drew a mix of vets, active military personnel, people in the know, and randoms off the street. Story Corps was there, too, recording the stories of anybody who felt like sharing. But the heart of the installation were the notes that civilians and vets left for one another. People put their questions and thoughts onto cards that read, “I am a civilian,” or “I am a vet,” and posted them to a bulletin board. By Friday, which was the day the installation closed, the notes spread across one of the walls of the hut, creating a kind of open-ended conversation. Here are some of my favorites…I only wish we could see what the answers would be!

What was cool and interesting about this project was that it gave folks a new context in which to ask these questions. It took a conversation that usually happens behind closed doors, if it happens at all, and put it in a little yellow hut, in one of the busiest places on earth. When you remove the clinical frame, these conversations become less fraught, and more open. The writing itself was a valuable process–there was something cathartic in putting your question to paper, and posting it up for people to see. More importantly, it gave us a platform on which we could speak, be heard, and engage with each other, which speaks to the possibilities in public art to mobilize, catalyze, stir up the pot. But it’s only one step. It will be interesting to see what, if anything, Matter Practice and Story Corps do with the questions, dialogues, and stories they gathered. Otherwise, it’s just talk. And you know what they say about that.

On Veterans Day

Photographic coverage of Veterans Day around the country at BagNews…

I updated this post today, after reading this piece, which Nicholas Kristof wrote for the New York Times. It’s about a combat veteran who commits a heinous crime. He is only 25 years old. He is a decorated Sargeant and has no criminal record. So how, and why, Kristof asks, did this happen? He writes,

“I don’t know just what could have led an apparently normal young man to commit such a crime. All we know for certain is that a caring, much loved woman here in Delaware has been horrifically murdered, leaving a vacuum of sadness and a vexing uncertainty about whether there is a link to distant wars.”

Kristof contextualizes the crime and the perpetrator without forgetting the victim and the tremendous loss her family and community faces. By doing so, he raises an essential question about the costs of war beyond the combat zone. In Kristof’s thinking, and I agree administrations who wage and support these ware are too slow to bear the burden of their ripple effects.

Freelance journalist Michael Yoanna created this tip sheet for journalists who cover veteran and military suicides. In one, Yoanna, who is currently directing and producing a documentary about a group of veteran cyclists recovering from war, writes,

“Don’t always assume the worst outcome. Yes, there is much reporting to be done on the themes of homelessness, drugs, homicide, suicide and harassment of wounded soldiers by the military. There are also many inspiring stories of veterans returning home and healing their wounds of war and persevering. There are many who have considered suicide and have found the resources and support they need. Telling their stories can be very powerful and inspiring.”

Yoanna’s work does double duty. Not only does he seek to motivate reporters to do better work, he also goes after institutional stigma within the military. In a scathing, investigative piece published in 2009 by Salon, Yoanna exposes the military’s resistance to diagnose PTSD, and its disturbing pattern of labeling vets with “childhood trauma” or “personality disorders” instead. Earlier that year, Salon reported on a review by the Department of Veterans Affairs to investigate 72,000 veterans who received monthly disability payments for psychological trauma. The review was halted after a veteran in New Mexico shot himself in protest.

A predilection to place blame on the victim of trauma is as old as trauma itself. So is the tendency to objectify the victim’s experience. Which is why I like Claire Felicie’s black and white portraits so much. They are close. Intimate. Vividly detailed. They make you feel as though you’re in the company of very old friends, or at least, men and women you might relate to. Check them out here.