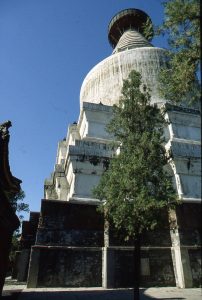

Honghuasi (Monastery Honghua; Chin.: 弘化寺)

Honghua si is located in Zhuandao Village (轉導村), Minhe Huizu Tuzu Autonomous Prefecture (民和回族土族自治縣), Qinghai Province. It was built in 1442 in memory of Shakya-ye-shes, a dGe-lugs-pa high priest, who was granted the tile of Daci Fawang (大慈法王) by the Ming court and died in 1435 on the way back to his homeland from the capital of Ming.

What should catch our attention is that Honghua si was not merely a Buddhist monastery, but also played a significant role in meditating between Ming China and Mongols. The relationship between dGe-lugs-pa and the Ming court was rather a relationship including three parties, China, Mongols and the dGe-lugs-pa of Tibet.

Unlike the other two imperial titles (Dabao Fawang 大寳法王 and Dasheng Fawang; 大乘法王) granted by the court, the title of Daci Fawang was terminated later on, however. Nevertheless, the dGe-lugs-pa succeeded in maintaining preferential treatment from the Ming court on the ground of constructing Honghua si at the site of Shakya-ye-shes’s death. What’s more, Honghua si is said to be a chijiansi (敕建寺), which means it was constructed by imperial order. Honghua si served as a substitute for the role of Daci Fawang in terms of maintaining the relationship between the Ming court and the dGe-lugs-pa, one sect of Tibetan Buddhism. What kept the two parties close were that Honghua si sent tribute to the Ming court frequently while the Ming court was responsible for the expense of repairing the monastery.

Due to its crucial location, Honghua si also served as a military institution in order to resist Mongols, who had been active in Qinghai region in the course of the Ming dynasty. Though, the dGe-lugs-pa was in a close relationship with the Mongols, it might be improper to conclude that the dGe-lugs-pa was pro-Mongols. The 3rd Dalai Lama’s visit to Honghua si was a critical event that indicated the dGe-lugs-pa’s missionary activity towards the Mongols would not be against the Ming court’s interests in this area.

Besides considering Honghua si’s functions above, what ought not to be overlooked is its being a powerful political unit in this region. Its political function was executed mainly through maintaining the fortress and beacon tower as well as recruiting soldiers for the Chinese army with the benefit of having Qing China acknowledge its ownership of tax-exempt farmers. Honghua si did not only have political power, it also gained economic power by accumulating land under the pretext of fulfilling its responsibility of providing horses to the courts. Its both political and financial authority in the region was not disturbed by the courts. What differentiates Honghua si from other Buddhist monasteries also includes that the abbots of it were hereditary.

Its importance of maintaining stability in Qinghai was acknowledged, thus supported by the Ming court. Honghua si, as a local Tibetan religious authority played multiple roles during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Resource:

Otasaka, Tomoko, A Study of Hong-hua-si Temple Regarding the Relationship between the dGe-Lugs-Pa and the Ming Dynasty, Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, 1994

Entry by Lan Wu, 2/23/07