Da Huguo Renwang Si 大護國仁王寺

The Da huguo renwang si was built during the years 1270 to 1274 on the Gaoliang river outside of Beijing. The temple owed its founding to the Empress Zhaorui shun-sheng (Mongolian Cabi or Cabui), the principal wife of Qubilai and mother of his chosen heir, Jinggim. Because of the generous patronage of the imperial family, the temple was extremely wealthy. In the Beijing metropolitan area it owned 28,633 qing 51 mou of irrigated fields and 34,414 qing 23 mou of dry fields, as well as the rights for forests, fisheries, moorings, bamboo and firewood in twenty-nine places. In also owned land in fifteen places around Beijing where jade, silver, iron, copper, salt and coal were produced, in addition to 19,061 chestnut trees and a wine-shop. In the Xiangyang region the temple owned 13,651 qing of irrigated and 29,805 qing 68 mou of dry fields. In Jianghuai it owned at least 140 wine shops. The temple also owned many houses and halls, and had a total of 37,059 tenant families as well as 17,988 families providing corvée labor. This list of property is drawn from an inscription written by Cheng Jufu, available in the Cheng Xuelou ji (see Franke 1984 for full reference).

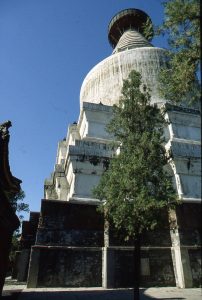

In the fourth month of the Yuanzhen reign year yi-wei (1295), the Tibetan cleric (and posthumously declared Imperial Preceptor) Sga A gnyan dam pa kun dga’ grags (Ch. Gongjia ge la si or Dan pa 膽巴) received an imperial summons to become abbot in the Da huguo renwang temple. The Treasury (tai fu) was ordered to prepare an elaborate welcome ceremony on par with those prepared for the emperor himself, and many officials escorted Danpa/Dam pa Kun dga’ grags/Dan pa to the temple. Later Dan pa was also buried there in the Qing-an stupa. His relics were taken to the stupa by the mayor of Da du [Beijing], along with a retinue of servants and musicians, by order of the emperor Chengzong.

In 1311, An pu, son of the disgraced Yang, became commissioner of the Huifu yuan (會福院), the name by which Da huguo renwang si was known by between the years of 1310 and 1316. At the same time he was ennobled as the Duke of Qin and he was also once again holding the post of commissioner of the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzheng yuan 宣政院). An pu had been dismissed from this post in 1291 because of widespread resentment against his father, who had destroyed the tombs of the Song emperors during a zealous campaign to convert sites in Jiangnan into Buddhist temples.

Sources:

Franke, Herbert. 1984. “Tan-pa, a Tibetan lama at the court of the Great Khans,” Orientalia Venetiana, Volume in onore di Leonello Lanciotti. Firenze: Leo s. Olschiki Editore. pp. 157-180.

Franke, Herbert. 1983. “Tibetans in Yuan China,” in China among equals: the Middle Kingdom and its neighbors, 10th-14th centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sperling, Elliot. 1991. “Some Remarks on Sga A-gnyan dam-pa and the Origins of the Hor-pa Lineage of the Dkar-mdzes Region,” in Ernst Steinkellner, ed., Tibetan History and Language: Studies Dedicated to Uray Gyeaza on his Seventieth Birthday, Vienna. pp. 455-465.

Entry by Stacey Van Vleet, 2/4/07

user-1541794744