Tibetan Buddhist Canon Texts Printing in Qing

It became a tradition for the emperors to sponsor printings of the Tibetan Buddhist canonical texts from Hung Taiji and onwards in Qing dynasty, both at Mukden (present-day Shenyang) and at Peking, which served as a hub of the vast project. One way to accomplish this task was to establish an imperial publishing house, otherwise known as the palace publishing house.

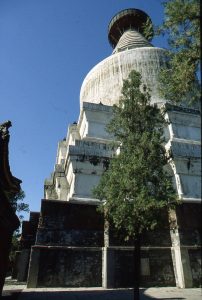

In comparing the printings of the Buddhist canons in the Qing and in Yuan and Ming dynasties, the sponsorship of publishing was dramatically shifted from Tibetan lamas (who occupied official posts in the Yuan court) directly to the Qing emperors. Emperor Yongzheng (r. 1723-35) established a Buddhist publishing house where many Buddhist canons were published. One monastery in Beijing, Songzhusi Temple (Chin.: 嵩祝寺, within the Imperial City), emerged as a central site for printing Buddhist texts. The site of the Songzhusi Temple had been the location of the printing workshops in Ming dynasty, called Hanjing Chang (Chin.:漢經厰) and Fanjing Chang (Chin.: 番經厰), literally translated as Han canons workshop and “Barbarian” [i.e. Tibetan] canons workshop, respectively. Emperor Yongzheng re-established the Songzhusi Temple in 1733, and it was moved to the current location by Emperor Qianlong in 1772. A number of canonical texts were printed in this printing workshop.

What is also interesting is that the Qing court encouraged having the Tibetan Buddhist canonical texts translated into various languages, for instance, Manchu, Chinese and Mongolian. The Mongolian language was one of the languages promoted by the Qing court. Mongolian appeared not only on steles, tablets, etc., but also on the guidebooks to Mount Wutai, such as the Qingliangshan xin zhi (Chin.: 清涼山新志), a fine new version of a Buddhist guidebook to Mount Wutai and its temples, edited by Lao zang dan pa老藏丹巴(a Chinese monk), in ten juan卷 in 1701, as well as an expanded version in twenty-two chuan卷 that was published in 1811. Both editions were published by the palace publishing house. Several Qing emperors visited Mount Wu-tai, where Tibetan Buddhist lamas were active then. Compiling and publishing the guidebooks for the Mongols, therefore, deserves more attention in terms of the triangle relationship among the Manchu court, the Tibetan Buddhism and the Mongols that potentially threatened the Manchu in the frontier areas.

These printed texts were mostly purchased by visiting Mongolian lamas for their home monasteries; however, it would be improper to think that all these texts were for sale. The Tibetan Buddhist canons were exclusively distributed as imperial gifts. Copies of them were scattered throughout the country and even reached as far as Central Asia.

Taking over the publishing houses was important for the Qing court to manipulate, recreate history, thus, to reconstruct the ideology, ultimately, legitimize the political system. Several selected published editions of the Tibetan Buddhist canon and other texts follows[[#_ftn1|[1]]],

The Kanjur in 108 volumes (1684-92; 1700; 1717-20; 1737 and in ca. 1765)

The Tenjur in 225 volumes (1721-24; 1742-49)[[#_ftn2|[2]]]

The Manchu Kanjur (1772-1790)

One edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon (1738)

Two editions of the Tibetan Buddhist Kanjur (1692 and 1700)

The Mongolian canon of 1718-20

The Qingliangshan xin zhi清涼山新志in ten chuan (1701)

The Qingliangshan xin zhi清涼山新志. In twenty-two chuan (1811)

Sources:

Crossley, Pamela Kyle, The Rulerships of China. The American historical review, 1468-1483. 1992

Farquhar, David M, Emperor As Bodhisattva in the Governance of the Ch’ing Empire. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38 (1), 1978

Uspensky, Vladimir, The ‘Beijing Lamaist Centre’ and Tibet in the XVII-XX century. Tibet and her neightors.

Van Vleet, Stacey, “Entry of Yuan Canon printings”

Entry by Lan Wu 03/14/07

[[#_ftnref1|[1]]] This is not an exhausted list. Other printed products range from a pocket-size Heart Sutra in Tibetan with both Manchu transcription and Chinese translation, to huge works like, the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in a Hundred Thousand Lines, were also published in Beijing. For further information, please consult with The ‘Beijing Lamaist Centre’ and Tibet in the XVII-early XX century by Vladimir Uspensky.

[[#_ftnref2|[2]]]Another resource mentions that the Bstan-‘gyur, and its publication in 226 volumes, which was the complete translation into Mongolian of the Tibetan supplementary canon was published during 1741 to 1749. Both of them may refer to the same printed Tenjur.