Juyong Guan 居庸关

The Juyong Gate was constructed between 1343–45 at the orders of the last Mongol emperor, Xundi (1333–67). According to its inscriptions, Dynastic Preceptor Nam mkha’ seng ge, a Tibetan lama of the Sa skya lineage, presided over the planning and construction of the gate and stupas, which were consecrated upon completion by Kun dga’ rgyal mtshan dpal bzang po (1333–58), one of the last Imperial Preceptors, also a Tibetan lama of the Sa skya lineage. Inscriptions also state that the emperor ordered its construction “in order to bring happiness to the people who pass under the stupas and receive thus the Buddha’s blessing.” See images here.

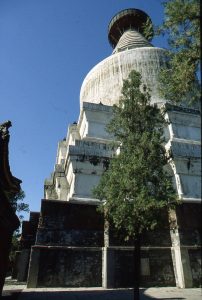

The Juyong Gate was built at a strategic pass just south of the Great Wall and northwest of Beijing. The arched gate was originally built as a base for three stupas (which disappeared and were replaced with wooden pavilions by 1448), and the architecture of the structure was in the Tibetan style. Stupa-arches were a completely Tibetan architectural form, introduced to China via the Mongols during the Yuan dynasty, and served the same function as they did in Tibet, standing at the entrance to important cities. The Juyong Gate may have been one of four planned gates intended to guard the four directions of the capital.

The arched passageway is carved with relief images that represent a highly developed state of lamaist art, which some link to the tradition established by Anige (1243–1306), the influential Nepalese artist invited to Khubilai’s court at the suggestion of ‘Phags pa in 1260. Prominent among the carved reliefs are images of the guardians of the four directions as well as mandalas of the five meditation buddhas, each of whom are associated with one of five directions (four directions and the center). The depiction of cosmological symbols based on four and five directions seem to be a reflection of the Mongol adoption of an originally Indian cosmology (four-directional) as well as a Chinese cosmology (five-directional). The idea that the Mongol rulers were guardian kings ruling over different directions (displaced onto actual geographies) was one of many religious conceptual models used to legitimate Mongol dominance.

The most significant aspect about the gate is its use of the above cosmological imagery together with inscriptions in five languages (Chinese, Mongol, Tangut, Tibetan, and Sanskrit) that posthumously articulate the divine nature of Khubilai Khan. Although the multilingual inscriptions differ subtly in content from each other, the Mongol inscription has been interpreted as elevating Khubilai Khan as a reincarnation of Manjushri, the resident bodhisattva of Mount Wutai in China. Such an identification of an emperor with Manjushri was unprecedented (and not mentioned in Chinese inscriptions due to incompatibility of the concept of reincarnation with Chinese Confucian sensibilities) and signaled a first step toward the role that Mongol emperors would later take as reincarnations of Manjushri/Manjusri. This use of the Tibetan concept of reincarnation together with the association of Manjushri with China (where the Mongol rulers resided) cleverly solidified Mongol legitimacy as religious authorities. Its significance as a religious-political model continued beyond the fall of the Yuan dynasty and was eventually passed onto the Qing.

Sources:

Patricia Berger. Preserving the Nation: The Political Uses of Tantric Art in China. In Later Days of the Law: Images of Chinese Buddhism 850–1850. Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas. 1994. pp. 103–07.

Heather Karmay. Early Sino-Tibetan Art. Aris and Phillips. 1975. pp. 21–27.

Franke, From Tribal Chieftains to Universal Emperor and God p. 64–72

Entry by Eveline S. Yang, 2/06/07