Corduroy

Corduroy is an extremely heavy-duty twill fabric, composed of twisted fibers that lie parallel to one another, resembling a ‘cord.’

Resources for Tibetan History Scholarship

Corduroy is an extremely heavy-duty twill fabric, composed of twisted fibers that lie parallel to one another, resembling a ‘cord.’

|

| Boots |

Cloth boots are made of thick cloth or canvas and they are soft, flexible and lightweight.

History

Cloth Canvas Corduroy Velvet Leather Felt Silk Cotton

Function & Purpose: What were each of these textiles mainly used to make in Tibet? Given the unique characteristics of each type of textile: Do the properties of a textile make it particularly suited for use in making a certain item? Do practical concerns for the function of an item outweigh the traditional craft and construction of the item? What purpose did the items made from each particular textiles serve? How have the function and purpose of these items changed and/or evolved over the years, within the context of Tibetan tradition and culture?

Form & Style

Given the effect that the type of textile used has on the form and appearance of an item: Were certain textiles reserved for making traditional, seasonal or ceremonial items? Which textiles were used for: traditional, seasonal items and ceremonial items? How has the form and style of these items changed over the years? How similar or different is the style of Tibetan clothing when compared to inhabitants of the surrounding areas?

*This project is currently under construction, though the finished product should roughly follow this outline. The goal of this project is to unite the research from two separate object biographies under the general category of textiles . The object biographies were written on a pair of Boots and a Tibetan Silk Dancing Dress, which are both in storage at the American Museum of Natural History. My hope is that by providing general, easily accessible information about various textiles (that continue to be used in the production of materials in Southeast Asia) to other students (especially those undergraduate students who are new to the field), that they will be more informed and more curious to research and explore other material objects. As the research continues, perhaps we can further relate the rich culture of Tibet to contemporary clothing and traditional costumes.

Classification of Materials:

Weaves:

Symbols:

An American diplomat, W.W. Rockhill, who was influential in thought and action to the Far East once said, the natural conditions have exercised a marked influence on the degree of culture of Tibet and must not be lost sight of in any study of the inhabitants. Rockhill’s idea is vitally important in researching discussing traditional Tibetan clothing or outerwear, such as boots and dresses.

Related pages:

[1] Notes on the Ethnology of Tibet by W.W. Rockhill P. 673

by Victoria Jonathan

Jacques Marchais (1887-1948) was a woman

Jacques Marchais (1887-1948) was a woman

who had an early interest in Tibetan culture and who built a museum on Staten Island that she thought of as an educational center to provide American people with a place of encounter with the East. This article relates the biography of both Jacques Marchais and the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art , which raises a few questions about museums in general.

who had an early interest in Tibetan culture and who built a museum on Staten Island that she thought of as an educational center to provide American people with a place of encounter with the East. This article relates the biography of both Jacques Marchais and the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art , which raises a few questions about museums in general.

The information provided in this article comes from different sources: an exhibition held at the Jacques Marchais Museum, press releases from her gallery and museum, correspondance, autobiographical notes, newspapers, and articles by the most recent curators of the museum.

She was born Jacques Marchais Coblentz in 1887 in Cincinnati (Ohio). Her father died when she was little and her mother sporadically took care of her; she went to different orphanages and homes during her childhood.

She started at age 3 in Chicago a career as a child actress, known as Edna Coblentz or Edna Norman (her mother’s family name), both names her mother thought more appropriate for a stage career. Her mother put her on the stage because of financial issues. She performed in quite notable plays at the time (like A White Lie and Silver Shell at Hooley’s Theater, and A Modern Match at the Shiller Theater). She was also invited to wealthy families’ houses in Chicago to perform recitals (among them, the crime boss Mike McDonald), families who paid for her education.

At the age of 16, she traveled to Boston in a comic play by George Ade (one of the most popular writers in America during late 19th-early 20th century), Peggy from Paris, where she met her first husband, Brookings Montgomery, a wealthy MIT student. Their marriage was reported as scandalous in the newspapers and Brookings’ family disinherited him. The couple had three children: Edna May, Brookings Jr. and Jane, and later went to live with Edna’s husband’s family in Illinois because of their financial problems. They divorced in 1910.

Edna was later briefly married to a hotel manager, Percy S. Deponai, and divorced in 1916-1917.

Some questions are raised about Jacques Marchais’ name. How come she had a French male name and changed it a few times in her life? She reported that her father (John Coblentz) chose this name before her birth and kept it even though she was a girl. Her mother renamed her for her stage career as a child. She later took up her supposedly birth name until her death, a name she used in her career as a collector. {1}

In a context of war and crisis of Western civilization, many American intellectuals grew an interest with Eastern culture and theosophy. When Jacques Marchais moved to New York in 1916 in order to pursue her acting career, she took part in a social circle of artists, travelers, scholars, scientists and aristocrats who were all curious about Asian spirituality and Buddhism. Jacques Marchais can be thus said to one of the first active participants in the beginning history of American Buddhism.

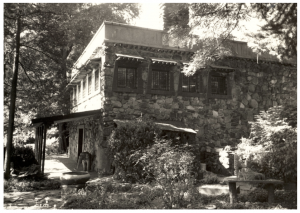

In about 1920, she married a businessman from Brooklyn, Harry Klauber (1885-1948), the owner of a chemical factory. They moved to Staten Island in 1921 with her children. At the time, Staten Island was the countryside. They built a house there, which they thought of as a haven of peace where to welcome their friends.

Among their friends:

➢ Claude Bragdon (1866-1946) was an American architect who moved to NYC in 1923 and worked in the theater world. He was interested in yoga, theosophy and Buddhism. He wrote books like Old Lamps for New : Ancient Wisdom in the Modern World (1925), An Introduction to Yoga (1933), More Lives than One (1938). {2}

➢ Syud Hossain (d. 1949) was a friend of Gandhi who was active in the Indian Independence Movement. He exiled himself to the United States to find support for Indian independence, giving lectures and writing articles and books. In 1933, Jacques Marchais helped him organize the “Roundtable of Contemporary Religion” in New York.

➢ Ruth St. Denis (1879-1968) was an American dancer who founded the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in 1915 with her husband Ted Shawn in Los Angeles. First a vaudeville dancer, she created her own style of dance based on her interest in Indian philosophy and ancient cultures. She was the teacher of Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Louise Brooks. She had a great influence on modern dance.

An article published in 1937 in a Staten Island newspaper reports on a talk that Bragdon gave at the Klaubers’ house :

“the essayist and theatrical designer said civilization is now in masculine form – full of hatred and war. (…) ‘What we should strive for’, he said, ‘is a unity of being. The East has a technique for attaining this unity. It is called Yoga, which means many things; but fundamentally it means to recapture one’s birthright. Individualism has never been separated from the universal spirit. Yoga is a system that involves emotions and self-obligations.’ (…) The living room of the Klauber home provided an excellent setting for Mr. Bragdon’s talk. Oriental lamps, statuettes, vases and tapestries fill every nook and cranny. The persons who attended were all interested in thet East – its religions, its civilization and its philosophy.”

Why would an American actress born in Ohio have such a deep interest in Tibetan culture, in a time when very few people in the Western world had such interests?

In her own words, the genesis of this passion for Tibet was to be found in childhood memories, and particularly in a trunk that contained thirteen Tibetan bronze figurines that once belonged to her great grandfather, John Joseph Norman, a merchant from Philadelphia active in the tea trade. {3}

In her article about Jacques Marchais, Barbara Lipton reports that “the records show that at least ten of the figurines were purchased in 1935” (Lipton, 10). So, is this story the beginning of it all or a lie? Anyway, this story was highlighted in her public relations exercise. In a press release entitled “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception” that documents the opening of the gallery, Jacques Marchais uses this story to explain her drive to build such a collection:

“When Jacques Marchais was between four and five years old, her mother opened a chest which had been stored in the attic of their home for many years. This chest had been unlocked only once during her mother’s childhood. It contained no family of old-fashioned dolls, such as might delight the heart of any little girl, but a collection of Ponist [Bon po] figures, brought from India by her great grandfather, Sir John Norman. He had become acquainted with several Lamas around Darjeeling, and one, who grew to be a particular friend, gave him this collection of thirteen Ponist figures, to which Jacques Marchais later added one, making fourteen in all of that particular type of figure. These original thirteen gods with which she played, while her childhood contemporaries mothered dolls, was the nucleus of the present-day and ever-growing Jacques Marchais collection.” An article published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on February 23, 1946, entitled “She Played with Statues Instead of Dolls – And the Little Girl from Ohio Came to Have the Richest Collection of Tibetan Art in the Western World”, relays this story.

Because of her health issues and the political context, and to her regret, Jacques Marchais never traveled to Tibet. Her knowledge about Tibet was acquired from books. Her transplantation of Tibet to Staten Island is thus quite an imaginary one. But she was very well-versed. Her library’s collection included all the literature about Asia available at the time in English, and many of her books are annotated by her.

Jacques Marchais began collecting Indian and Tibetan art in the late 1920s. By the 1930s, she had become a renowned collector and notable person in the field of Tibetology. She began to imagine a place to house her collection, an educational center that would be an encompassing experience for visitors and where she could share her interest.

|

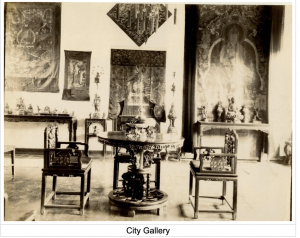

| City Gallery |

In 1938, she opened an Indian and Tibetan art gallery in the elegant neighborhood of Park Avenue (on 40 East 51st St, the building no longer exists and has been replaced by a skyscraper). For her, the gallery was a way to finance her project for a Center devoted to Himalayan culture: “The gallery is only a stepping stone toward doing something I think will be a help to humanity in the long run.” (Letter to Kate Crane-Gartz, January 6, 1940) She also said : “I only started this gallery as a fore-runner for the miniature copy of the Potala of Lhasa, which I hope to build on our hill adjoining the gardens, within the next five years. I hope to build it large enough to house 300 people at a time. It will be, of course, of fieldstone – the interior done in the color conducive to peace and meditation – with a huge Buddha smiling down upon them in a benevolent benediction.” (Letter to Claude Bragdon, February 6, 1940).

|

| City Gallery |

A press release entitled “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception” documents the opening of the gallery. It presents it as a haven of peace and spirituality: “There one may truly step into another world – a world whose people have not known war for many years, and whose spiritual side is magnificently represented by the various gods and goddesses (see Lha-mo for one) of the Tibetan pantheon, thang-kas (paintings), ritual implements and costumes used in connection with religious rites. Here visitors are always welcome.”

The gallery, which remained open for 10 years, provided her with funds for the building of the museum.

The museum

When Jacques Marchais and her husband Harry Klauber moved to Staten Island in 1921, he supported Jacques’ idea of building next to their house a Center devoted to Tibetan art and culture, consisting of terraced gardens, a library, and a museum. {4}

She started the Center by designing a garden that she named « Samadhi », a Sanskrit word for « establish, make firm » and a Buddhist term for describing a high level of meditation.

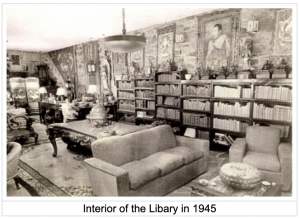

The library was then built, between 1943 and 1945. It was meant as a non-profit place for research for members only. It was comprised of about 2000 volumes of “books on occult subjects, Asiatic Art, Comparative Religions, Symbolism, Color, etc.” (Library press release). Jacques Marchais had built a comprehensive collection of the literature available in English on these subjects at the time.

In a press release, Jacques Marchais announced the opening of the Library on July 29, 1945, and defined the terms of her Library. {5}

|

| Interior of the Libary in 1945 |

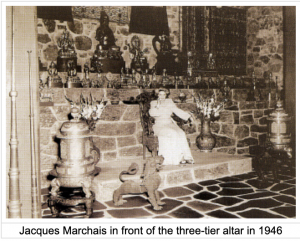

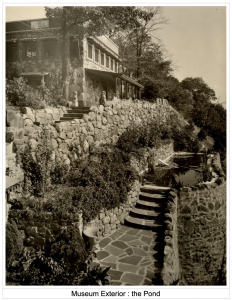

She later built the museum to house her collection of Himalayan art. She called the museum the “Temple Room” or the “Chanting Hall”, and wanted it to look like a Himalayan temple. Her influence for the architecture of the museum were the Potala of Lhasa and a pavilion called “Chinese Lama Temple: Potala of Jehol” she had seen at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. {6}

She was inspired by pictures from her books, and included such details as the long flight of stone stairs leading to the Center, a pond, meditation cells, trapezoidal windows, pagoda shaped roof. She was personally involved in the construction of the center. She designed the whole project (she even made prayer-wheels herself), and entrusted Italian immigrants with the task of building it. She conceived of a Tibetan Buddhist three-tiered altar made of mica for the room. The objects displayed on the altar are of sacred and spiritual meaning.

.

|

| Jacques Marchais in front of the three-tier altar in 1946 |

She expressed her refusal to hire architects in a kind of “feminist” stance: “Each stone was lovingly picked by me and hauled that has gone onto its walls. And I was successful in getting it up without benefit of one architect, contractor or purchaser of the materials. I was able to prove to myself that one woman could do it if the talent was great enough and the urge and willingness to work hard was strong enough.” (July 27, 1945, on building the Library) {7}

She envisioned her Center very precisely, as she explained it to a friend: “The seven terraced gardens are completed but we are now engaged in blasting out rock in the side of the hill for the future potala. The building will face the southeast; and it is situated on the side of a hill (the highest hill from Maine to the Florida Keys) on the Atlantic Coast – but within 65 minutes of 51st Street. There will be ‘The Chanting Hall’, which will hold about 300 people on the top terrace – an Asiatic library, museum and my office on the second terrace – and on the third – will be storage rooms, bams for a few goats, etc. – and a large space in front of these buildings which will be flagged. Here we can give the cham (traditional sacred dances) and observers can look down from the upper terraces at the spectacle below. I have the gorgeous Tibetan costumes and masks that are worn in these dances.”

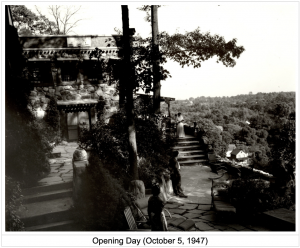

Jacques Marchais and her husband broke ground for the museum in 1941, and the construction went on from 1942 to 1947 (except in 1943 when it was interrupted because materials were scarce in a time of war). Jacques Marchais maintained her gallery during the construction.

When the Center opened in 1947, it was widely released in the national press (articles in the New York Herlad Tribune, Life, Buffalo Courier Express…). An article in Life Magazine (December 8, 1947 : « New York Lamasery : A New Tibetan Temple Bewilders Staten Island ») said: « Now the structure will be opened for ‘meditation’ to devotees of Tibetan culture like Madame Marchais, whose only regret is that she never has been to Tibet. »

|

| Opening Day (October 5, 1947) |

Jacques Marchais was greatly involved in this museum project:”My all has been given to this venture – my strength, my health, what little money I had, the collection and the building of the Library and Museum. There has not been one bit of outside help! I have not needed it. No reward is expected, other than the realization of my one ambition – which has been to house in permanent buildings my books and a replica, as near as possible, of a Tibetan ‘Chanting Hall’ with its golden altars, deities, religious implements, etc. For it is to prove to be a cultural benefit to those persons of the Western World who are seeking a better understanding of their Oriental brothers – their art, their religion and their philosophy.” (November 30, 1944)

But unfortunately, she died on Februray 15, 1948, four months after the Museum opened, and her husband died seven months after her.

In 1947, Jacques Marchais’ collections included 3000 valuable pieces of Tibetan art (thangkas, ritual implements, textiles, altar sets, furniture, jewelry, wood-blocks, and 1500 bronze deities).

After both Jacques Marchais and Harry Klauber’s death, the museum was managed by Helen A. Watkins, a friend and neighbor, and a board of trustees was formed. From 1953, she opened the museum to the public on an irregular basis. In 1959, the museum offered a refuge on Staten Island to the Dalai Lama, as it is reported in an article of the New York Times from April 4, 1959 (“Tibetan Sanctuary on Staten Island Contains a Spiritual Quality – Dalai Lama Gets Invitation Here”). She did what she could to maintain the museum, but it soon began to deteriorate, and hundreds of objects from the collection were sold off or stolen. Many objects from the Jacques Marchais’ collections were thus scattered in other Himalayan art collections; as a result, some of these objects are now part of other museums’ collections in United States (for instance, the two lions’ statues that appear in some pictures of Jacques Marchais’ gallery and museum belong now to the Asia Society, and have even become the Asia Society’s logo). Before her death in 1971, Watkins sold the house and terraced gardens next to the museum that had been the Klauber’s home.

From 1971, the museum was run by volunteers and a small board of trustees. It was open very irregularly. In the mid-1970s, the museum was taken care of for the first time by paid conservator and curator, benefiting from State financial help.

In 1985, Barbara Lipton became director and curator of the museum. Under her direction, a catalogue of the museum was published in 1996, including participation of renowned Tibetan scholars such as Donald S. Lopez. More than 200 objects have been added to the collections during this period. In 1991, the 14th Dalai Lama came to the museum and blessed the museum’s altar and collections. It is also during this period that the Center became known as the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art.

Since 2004, director Meg Ventrudo and curator Sarah Johnson have begun taking care of the museum collections: building renovation, proper storage and conservation of the collections, inventory… These basic operations have not have been completed since the museum’s opening because of management and financial issues. Few archival records exist of the the provenance of the museum’s collections, which make them difficult to trace.

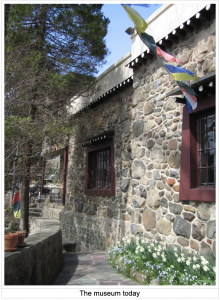

| The museum today |

Today, the collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art include about 1200 pieces of Himalayan art. Only 1000 objects remain from her original collection of 3000.

In building her Center, Jacques Marchais’ goal was to educate American people about Tibet: “The purpose of our corporation is… to make the American public more conscious of things Tibetan from an educational point of view.” (Letter to the Department of Licenses, July 2, 1940). She saw herself as an “instrument” in the diffusion of Himalayan culture: “Please do not think that I am an egotist, for no one knows better than I that I am but an instrumentused to preserve the art of an ancient people and to present it to a younger generation.” (Letter to Dr. Hans von Koerber, Professor, University of Southern California, December 11, 1944) In a time of Depression and World War, her aim was to bring a little bit of peace and spirituality to Western civilization. She felt she was charged with a mission that would benefit the entire world: “I have every hope that what I am doing, and the thought that is behind the scene of this particular endeavor, will prove a source of comfort to thousands.”

Ultimately, one could wonder what was her relationship with Buddhism. Was Jacques Marchais herself a Buddhist? In her time, Buddhism (known as Lamaism) was not well respected, and very little information about it was available in America (no Tibetans in the West, few translations).The vague idea people had about it came from the popularization of the “Shangri-la” through 1933’s novel Lost Horizon by British writer James Hilton – which described a utopian place of great harmony and a lamasery in the Kunlun mountains.

Jacques Marchais strongly identified with Tibetan culture and Buddhism, but never publicly claimed herself as a Buddhist. Rather, she showed an openness to all religions. Although she wanted her Center to resemble a temple, she did not conceive it as a place to convert people and proselytize, but rather as a place to educate them about Himalayan culture and spirituality. Her goal seems to have been more of a contribution to the mutual understanding of Western and Eastern cultures, and to religious tolerance. Nevertheless, she did express her belief in such concepts as karma and reincarnation among her circle of friends. {8}

How was the collection acquired? Jacques Marchais purchased items from dealers, auctions, and private individuals. She benefited from a period a chaos in Tibet and China. It was during this period, from 1911 to 1949, that Himalayan art was on the market for the first time, and that many collections were built in the West (for instance, the collections at the American Museum of Natural History, at the Newark Museum, and at the Philadelphia Museum).

In building her Center, Jacques Marchais had a wholistic approach of collections and context, spirituality and setting. Although she had never traveled to Tibet, she was extremely attentive to details and sought for authenticity.

In Sarah Johnson’s words, “Part of Jacques Marchais’ uniqueness as an institutional architect was her creation of a contextual setting that was conducive to the aesthetic appreciation of the artefacts. Affectionately terming her center a ‘miniature Potala’ or the ‘Potala of the West’ after the Potala palace, the historic home of the Dalai Lamas, in Tibet’s capital city, Lhasa, she wanted to evoke the architectural style of a Himalayan mountain monastery. The rustic fieldstone buildings themselves, as well as the objects contained in them, became tools for studying Himalayan identity. The environment of her centre’s location, with terraced gardens and a fishpond flowering with lotus, added to an atmosphere of serenity and beauty – an overall viewing experience that distinguished the institution from other art museums.” (Article in Asian Art)

Jacques Marchais’s project of a Museum of Tibetan Art, conceived as a “total” experience, raises some questions about museums and the way they display objects from different cultures. Is a contextualization of these objects necessary in order for the viewer to apprehend them? What is the role of architecture in museums? To what extent should the culture from which the objects come be represented?

Ultimately, Jacques Marchais can be considered a pioneer from different points of view. As a woman born at the end of the 19th century, she managed to live her own life and realize by herself a dream which was very singular at the time, to say the least. Her curiosity and imagination, as well as her drive to study with rigor, make her one of the first publicists of Tibet and Buddhism in the Western world. Given the popularity of Buddhism in America today, and of humanistic ideals of intercultural dialogue after World War II, Jacques Marchais can be said to have been a visionary.

|

| Museum Exterior : the Pond |

{1} “Edna was a stage name given me by my mother when she put me on the stage as a little child, and the name she usually called me – but, my baptismal name was Jacques Marchais Coblentz, which my father asked her to name me. The Jacques was his father’s name, and the Marchais was his mother’s maiden name. Her father was a sculptor. After I left the children’s father, I resumed my own name, which I had not used since Mother put me on the stage, at three and a half years of age. After my father’s death, that was. I have not used the name Edna since.“ (Jacques Marchais, Letter to Kate Crane-Gartz, December 3, 1945)

{2} Biography on http://www.lib.rochester.edu/index.cfm?PAGE=3514

{3} “One day my mother unpacked an old trunk that she had been keeping in storage (my curiosity was aroused and soon there began to appear from their shrouds of wrapping paper figurines most foreign to anything we Westerns are familiar with. Though I have never had any use or would not play with dolls I immediately took to these bronze figures. From then on they were my companions by day and my bedfellows by night. My mother never knew what they were except that they were brought to this country by her grandfather from Darjeeling. And it was not until I began to study and delve that I realized they belonged to the old Pon religion of Tibet. These figures were returned to their wrappings and relegated to the old trunk and placed in storage again, after I had outgrown my maternal instincts.

I never again thought of them until my mother’s death {1927}. Her belongings and the large old-fashioned trunk was sent to me. Upon going through her things I came upon the old loves of long ago and with a renewed and much more vital interest in them. I started to try to identify them.

I had been interested in India, her religion, her gods, etc. for some time. But nowhere in her old books were deities such as these. Only by accident had I come upon notes of mother’s grandfather on its old Shamanistic and Animistic Pon religion. Then the hunting began in earnest.” (cited in the current exhibition at the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art)

{4} In the library press release, Jacques Marchais describes her husband as “a ‘Rock of Gibraltar’ for her to lean on”, “giving her the necessary encouragement when things looked darkest and most discouraging for her and her work.”

{5} About the audience, she wrote: “This Tibetan Library will not be open to the public, but will be available to a selected membership of five hundred individuals only, who feel the literature to be found within its walls – in book and manuscript form – worthy their support. (…) These restrictions have been made to assure perfect peace and quiet to the members – and the exclusion of the merely curious and non-studious. The membership fees are to be used for the purchase of Tibetan manuscripts, books relating to Tibet – its life, politics, art, religion, etc., whenever available, and for the repair of bindings and the salary of a librarian-secretary.” About the nature of this institution (Library and future Museum), she said: “This project is strictly, in every sense of the word, a non-profit, non-sectarian organization. It is the only thing of its kind ever to be attempted outside of Tibet.”

{6} In a document entitled “Aims and ambitions of Jacques Marchais”, she explains her museum project in these terms:

“she is holding a museum to house the permanent Jacques Marchais Collection of Tibetan Ritual Art. This museum, which will have a large library for research and reference attached, is to be a miniature duplicate of the Potala in the forbidden city of Lhasa. It will be richly furnished and will have all those architectural details (in true Tibetan style) which make the difference (…).

For Madame Marchais, crusader in this field, has plans to endow her museum so that posterity may reap the benefits of her long and happy years of work. It is almost entirely due to her efforts that the true worth of Tibetan objects has become known in this country and their value as art recognized. »

{7} She also expressed: “I had to turn over my drawings – list of materials, etc. to ask an architect and from these drawings of mine he made the blue prints and filed the plans. (…) I was a lone wolf from the beginning to the end. When I found I had to have a requested archiect file my plans, I took three different men who did not know each other – gave them photos, my drawings and data – and told them to make the blue prints – I had a reason for doing this as you shall see. When they brought me the blue prints – they were alike of course. but each man had his name on the drawings, ignoring me entirely as the real architect. (…) It was because I knew what I was striving for – because I knew Tibetan architecture, symbolism etc. and was working for perfection that I insisted upon going it alone. You don’t have to be a registered architect to build beautiful buildings, but you do have to have a talent for design, authenticity etc. to do a good job. So, take heart you ladies who follow me. Express our ideas and don’t be afraid to carry them out. Only – don’t copy others. Be your own self – and good luck to you.” (J. Marchais, “The true story of the building of and designing of The Jacques Marchais Center of Tibetan Arts”, 1947).

{8} Her syncretic beliefs can be felt in a Poem she wrote on her 1944 Christmas card:

“Ad Coelum

At the Muezzin’s call for prayer,

The kneeling faithful thronged the square,

And on Pushkara’s lofty height

The dark priest chanted Brahma’s might.

Amid the monastery’s weeds

An old Franciscan told his beads;

While to the synagogue there came

A Jew to praise Jehovah’s name.

The One Great God looked down and smiled

And counted each His loving child;

For Tsirk and Brahmin, monk and Jew

Had reached Him through the gods they knew.

It is the deep and sincere wish that all men may reach the full realization that we are indeed all the children of ‘The One Great God’ and conduct ourselves accordingly.

Thus is my message to you – this Christmas day.”

She commented on this poem: “In no way am I prejudiced for or against the various religions of this world. In my eyes they are all good and certainly lead to the same ultimate goal, being the teachings of the Vedas, Zoroaster, Moses, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus or Mohammed. And I am sure that the one Great God counts each and everyone his child and cares little what our theological beliefs and metaphysical opinions may be or the Gods we know and reach Him through. The very fact that we are seeking Him means that we have already found Him. One of our laws should be tolerance of all religions and compassion for all their errors.” (Preface to Autobiography)

Exhibition at the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais” (March 18, 2007 – December 31, 2008)

Johnson Sarah, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais” (?), in Asian Art, April 2007

Johnson Sarah, “From Staten Island to Shangri-La: The Collecting Life of Jacques Marchais”, in Orientations, May 2007

Lipton Barbara, “History of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art and the Collections”, in Treasures of Tibetan Art: Collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, Oxford University Press, 1996

Marchais Jacques, “Aims and ambitions of Jacques Marchais”, New York, 1938

Marchais Jacques, “How the Jacques Marchais Collection had its Inception”, New York, 1938

Marchais Jacques, “The true story of the building of and designing of The Jacques Marchais Center of Tibetan Arts”, New York, 1947

Special thanks to Dr. Sarah Johnson, curator of the Jacques Marchais Museum, for her time and help.