Hundreds of years of development reveal a constantly changing skyscraper-studded Lower Manhattan skyline. Modern flashy buildings rise while aged relics retreat into the Manhattan schist, the foundation allowing the man-made mountains to protrude. A slight glimpse of nature hangs off the Financial District at Battery Park. Created by landfill, the manicured space includes a fort, statues, memorials and an unfettered view of the world beyond. Lying against the East River sits a cluster of 1970’s office towers. Catering to the world’s financial leaders, the buildings’ and their tenants cling to the Financial District through triumph and terror, serenity and flooding. On either side of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel entrance lie the International Mercantile Marine Company Building and Whitehall Building. Preserved artifacts each nearly a century old; they await time and surrounding structures to entirely overshadow them. Built through landfill and enormous wealth, Battery Park City lies on Manhattan’s southwest corner. Sitting neatly between the Hudson River and West Street, the neighborhood’s peaceful streets host an indoor shopping mall and thousands of residents and workers. West Street and FDR Drive enclose the remainder of Lower Manhattan. Inventions of Robert Moses, the frequently congested highways’ separate New Yorkers’ from the island’s most prosperous resource; water.

Lower Manhattan’s prominent location on the water sped the flow of development and travel. Millions of people entered America through New York Harbor; gazing at the eternally impressive skyline. Though once bringing hope to New Yorkers’, the sea creeps ever closer.

Hurricane Sandy flooded the Lower Manhattan skyline. Sea level rise maps paint a startling picture of a waterfront ¼ mile inland from present. Communities in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island face more imminent danger. Coney Island, the Rockaways and Midland Beach, like much of New York, developed because of proximity to water. City government and residents’ face the impossible decision of whether to stay and fight the inevitable or retreat and allocate resources elsewhere. Due to Lower Manhattan’s historical presence and wealth of economic and infrastructural resources, fight they must. Constructed walls and protections slow disaster while New Yorkers’ wait for miracles to appear beyond our lifetime. New York’s strongest asset becomes its greatest foe.

As sea level rise gradually shrinks the physical envelope of New York City, the universal nature of climate change brings the shared essence of life to the forefront. The same process affects different corners of the Earth in similar ways. Though having the potential to divide, the existentialist force should instead inspire us to see similarities.

The water adjacent to Lower Manhattan allows a view of the reflection of our creations. Together, the most rewarding and hurtful pieces of life manifest themselves in New York. All visitors are able to experience the architectural landscape of the Financial District, but the benefits are not equally distributed. The early flow of capital through New York Harbor fueled the construction of buildings throughout the City. Further exploration and creation of new markets led to larger and more profitable industries. Maintaining the growth we had become accustomed to required the development of new real estate ventures, such as Battery Park City and Hudson Yards. Once the only place for capital and wealth in New York, the culture of Lower Manhattan spread across all three hundred miles of the City through real estate development and gentrification. The greater the flow to the top, the larger the divide from the bottom. Emma Lazarus famously stated to “give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Masses continue to wander into and through New York City. Though no longer living in such crowded, squalid conditions life in New York City remains a battleground.

The photo of Lower Manhattan identifies various facets of New York City. Once used as a fortification against invaders of Lower Manhattan, Governors Island now provides an oasis from the dense city it protected. The fence on Governor’s Island obstructs the striking skyline.

The water splits the City while engulfing those closest to it. Highways separate New Yorkers’ from the peace and tranquility of the Hudson and East Rivers. The skyline of the Financial District creates an image of prosperity and peace, but blocks the view of poverty and crime beyond. New York has remained resilient and innovative through natural and human-made terrors. The City’s future remains uncertain; belonging in the hands of all users of the City, particularly planners.

Article published in the Fall Issue of URBAN, Supra. You can access it here.

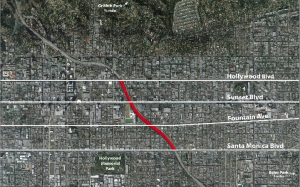

Both New York City’s recently opened High Line park, and Los Angeles’ answer to it, the Hollywood Freeway Central Park, are reminiscent of the City Beautiful movement – the turn-of-the- 20th century planning approach responsible for such enduring landscapes as Central Park and Prospect Park. A century later, cities are still building parks that reclaim and readapt space in unconventional ways. Today, new parks not only serve as destination points for residents and visitors, but they act as tools for increasing the city’s global profile.

Both New York City’s recently opened High Line park, and Los Angeles’ answer to it, the Hollywood Freeway Central Park, are reminiscent of the City Beautiful movement – the turn-of-the- 20th century planning approach responsible for such enduring landscapes as Central Park and Prospect Park. A century later, cities are still building parks that reclaim and readapt space in unconventional ways. Today, new parks not only serve as destination points for residents and visitors, but they act as tools for increasing the city’s global profile.