An essay by Jesse Albrecht, who served as a combat medic in Mosel, Iraq, 2003-2004

“I don’t know why I left, but I left on my own, and it won’t be long

till-I, till-I, till-I get on back home…blood, guts, sex and danger I

wanna be an airborne ranger…hi ho didlley bob, wish I was back on the

block, with that bottle in my hand-I’m gonna be a drinking man, I’m

gonna drink all I can, for Uncle Sam–re-up you’re crazy, re-up you’re

outta your mind…”

This weekend I spent chain smoking cigarettes and drinking, talking

with a friend I served with in Iraq—he just returned from Afghanistan.

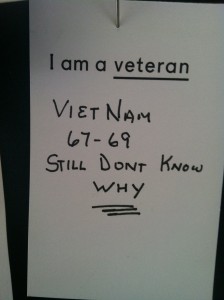

The point kept resurfacing of feeling great worth in a worthless

endeavor, and then feeling worthless upon returning home after a

deployment. When I returned from Iraq I felt like an alien here, Iraq

was my home, I had a purpose there, and all the continually fucked up

situations felt normal. Here the violence, aggression, and fear which

made me successful in Iraq continue to cause struggle and pain.

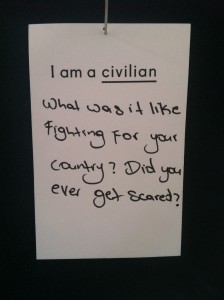

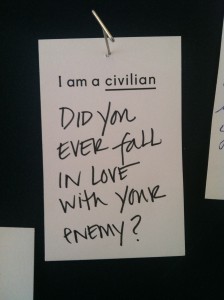

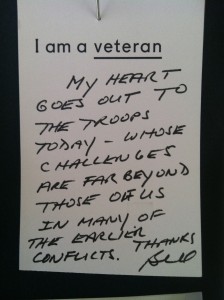

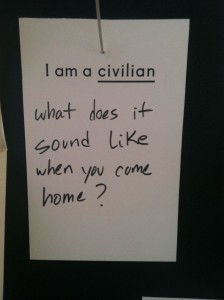

It is important to hear directly from the participants and the arts

provide form where the experience and its results can be remade into

something tangible. Something that allows the outsider

(non-combatants) a chance to feel a sliver of our emotions their tax

dollars paid for. It is vital to remove the spin from the combatants’

experiences.

The change started to resister for me when the Abu Ghraib pictures

surfaced and while I was disgusted like everyone else, I also

thought—well, shit, I would much prefer a naked pyramid any day of the

week over my head getting cut off and the video being posted on the

internet for the family to see…

But there are videos of American soldiers killing on the internet. The cycle starts and everything else falls away. Ideas of right and wrong are already conditioned out

of soldiers. Learning how to kill, wanting to kill, be rewarded for

it–having it be an honorable thing, is part of the training to become

a soldier. Seeing dead and blown apart Americans as a medic wore me

down and quickly. When we went out on security missions I hoped I

could kill who was trying to kill me. My thoughts, hopes, and dreams

of killing weren’t like the John Wayne myth, but an up close and

personal event, where I could watch someone’s head explode, either

from my bullets or buttstroke from my rifle caving their face in, or

maybe disemboweling them with my fighting knife I wore on my body

armor (without the ceramic plates that would stop bullets).

It is not the other that commits the atrocities that are part of the

war experience. It is people like me, an eagle scout, member of the

national honor society, my mother’s youngest son. It didn’t take me

very long to get to the place where I wanted to join the ranks of

atrocity, because it is the energy and essence of war, the most

beautiful and most horrible intertwined in a never ending knot. I

thank God I didn’t act on my thoughts, and now my thoughts can act on

me, and I act on those around me.

“Oh Mamma Mamma can’t you see, what this war has done to me…and it

won’t be long, till-I, till-I, till-I get on back home. “