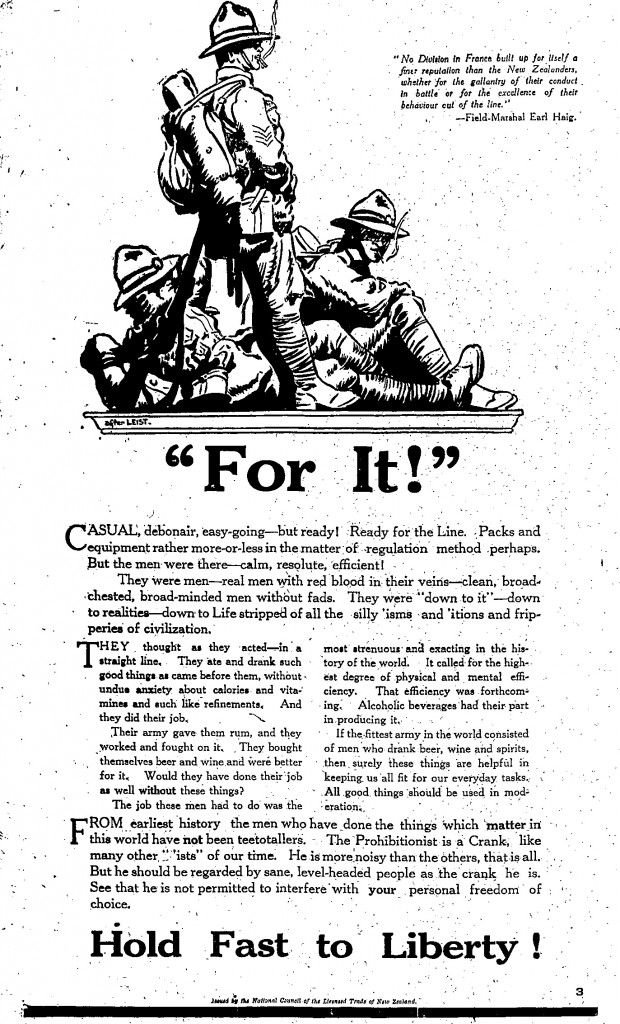

Take an original historic site, with a great story behind it from the most popular era of British history, sink a whole lot of money into it, and you have a recipe for a great museum, right? In fact, Bletchley Park is the worst museum I have ever visited.

My friend and I found ourselves with a morning to kill near Milton Keynes. As we drove around, I noticed signs leading to Bletchley Park, and I suggested that we visit, since I had heard interesting things about the site. After a slightly confusing entry process, we found our way to the main entrance. Fancy-looking concession booths awaited us, and to my surprise we had to pay fifteen pounds each to enter. This is unusual for a British museum – most of the best museums in the country are free. However, we were there, and we were bored, so we paid. We passed through a fancy-looking store, and into the main areas of the museum.

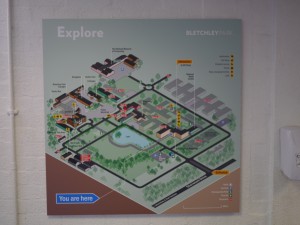

A map introduces visitors to the layout of the site, but fails to communicate anything about the content any of the buildings, perhaps because there is so little of the latter. There is no coherence or organization to the museum, with the possible exception of the main gallery downstairs from the entry. Here you can find what seems to be the prized exhibit – a working replica of one of Bletchley Park’s ‘bombes’ – a mathematical instrument that was a precursor to the earliest computers. This is an admirable idea for an exhibit. However, it was effectively closed-off while we were there because a film crew was doing something with it. As a result, we saw it from a distance, but weren’t able to read all the more detailed notes.

The same gallery contained a statue of Alan Turing, an exhibit about him, a helpful (albeit wordy) timeline describing the codebreaking process, exhibits on espionage in the Second World War and numerous Enigma machines. It is unclear how the espionage exhibits fit into the codebreaking theme and, as I will discuss below, they weren’t great. Aside from the timeline, there is no particular order to the gallery. If anything, it is organized by the perceived strength of the exhibits: the bombe machine is first, followed by Turing, followed by the enigma machines then by the miscellaneous other exhibits on espionage and Japanese codes . The timeline stretches along one wall.

This gallery was okay, albeit small, and we proceeded to look around the rest of the museum, hoping that there would be some more interesting material (the site is, after all, quite large). What we found was almost nothing. Along with its lack of organization Bletchley Park is grossly incomplete. Most of the codebreaking sheds are awaiting renovation, and signs to the effect that new exhibits will be coming are almost as common as signs asking for more donations. This is a huge problem: in its present state they should not be charging money, let alone a large amount equivalent to a major New York art museum. London’s(free) Imperial War Museum’s display on espionage offers a stronger historical narrative and better artifacts than this.

Why create new content when you can borrow from a better museum?

The incomplete state of the museum is clearest in the one hut that is open and does contain exhibits, as well as a couple of rooms half-heartedly done up with wartime propaganda posters and a few antiques, including Alan Turing’s old office. Each separate room contains a different exhibit. One is on carrier pigeons, there are two covering specific naval engagements related to the codebreaking process, and another, bafflingly, about the history of the German occupation of the Channel Islands. These exhibits are inconsistent (but usually bad) in quality. This is because they are almost all borrowed from other organizations with no attempt at renovating or updating them for a larger museum. Fonts, color schemes and the quality of posters are different in each room. One display consists of a set of posters where white text boxes were taped to white background posters. Another has a diorama in which mediocre kit models of a British warship and a German U-Boat sat side-by-side on a sea made out of green bubble wrap. A picture in an adjacent room about the opening of the hut shows Charles and Camilla pretending half-heartedly to admire the display.

Quality typical of exhibits in Hut 8 of the Bletchley Park museum

Another display about wartime British society in the main room had been lifted directly (presumably with permission?) from the (again, free) Imperial War Museum. The text for their own exhibits is much weaker, and suffers in comparison. Displays are wordy and poorly organized. They present an Anglo-centric view of the world, where Americans, Germans and Japanese people (in order of increasing foreign-ness) are definitely the ‘other’. A Japanese flag signed by friends of the soldier who carried it is described as ‘probably carried by a Kamikaze soldier’. Why ‘probably’? Maybe because there was no such thing as a ‘Kamikaze soldier’. Kamikaze were aviators who piloted explosive-packed aircraft into American vessels, so the flag (which can probably be traced, as my own grandfather did) is unlikely to have been from a Kamikaze mission. A small amount of research would have shown the curators that their description of the artifact was barking up the wrong tree, but I doubt they were particularly interested in portraying Japanese culture and history accurately. The museum seemed more interested in anti-imperial slogans on the flag, which are translated in a condescending manner.

Women, too, are accessories rather than actors in the narrative. The women who worked at Bletchley Park are consistently described as ‘girls’, thus replicating rather than analyzing wartime condescension. One display on a famous spy has a title about how the spy concerned gained success after the war in part because he acquired a ‘glamorous’ wife. It showed a picture of the couple, but did not give her name. Hot blondes, after all, speak for themselves, according to the authors . The implication was that had she not been so beautiful she would have been irrelevant to the story. In their attitudes towards race and sex, the curators seem to be living in the wartime era. They need to work out the difference between analyzing and simply repeating the cultural practices and biases of their subjects.

It is a scandal that this museum is open, and that it is charging money. The lottery board, the various corporate sponsors and the large numbers of people who visit need to start asking the Trust that runs the museum where the money is going, and why they are charging full price for a grossly incomplete museum. Presumably a large part of the cost has gone to creating the replica Bombe, but this (while interesting) is not an exhibit worth the high charge, especially given the excellence of the Imperial War Museum’s espionage section. The museum also had a large staff, with many tour guides, concession stand operators and other staff wandering around the rambling, unorganized site (I certainly hope they are paid, not volunteers). This is also presumably a drain on the finances. Perhaps they need to close the site and start finishing their museum? But then they won’t be able to rake in so much money from gullible consumers and tourists like me and my friend. The most charitable reading of the situation is that they have been trapped by the expense of the museum, and cannot afford to either close or finish it. The less charitable interpretation is that someone is making a lot of money from this abuse of England’s extensive Second World War heritage industry.

Museum display, or middle school project?

Gordon Brown’s apology to Alan Turing, which is reproduced in the display about that great scientist, ends with the words ‘You deserved so much better’. That is right – he, the other code breakers and paying visitors to this important heritage site all deserve much, much better.