In January they told us Americans, indicating the girls with their eyes, that Bologna was a fairly quiet little city and in our search for apartments we would have only to avoid two particular spots: the area around the train station, predictably, and the Via Petroni. Of the eight apartments I surveyed I chose one in the latter zone, building number seven. The residents were the only ones who hadn’t offered me coffee during the interview, but I supposed they had been nice enough regardless, and there was their dog Brando to consider. Brando took a liking to me right off. He was knee-high and fox-shaped and the pale yellow color of dry sand. He was one of two dogs I fell in love with that year, and, unlike the other, Brando barked in plain English and loved me back.

I wondered what could be so bad about this Via Petroni, which in daylight looked no seedier to me than any of the other streets in the center of town. It was connected to a square called Piazza Verdi and for that reason associated in my mind with the opera, tamest and most charming and decrepit of all the fine arts. In fact I was to notice a few days later that bordering Piazza Verdi was Bologna’s very own opera house, stately yet somehow unassuming. I imagined strolling home through Piazza Verdi in the evenings with violins playing, among wholesome choristers and intellectuals, among suited middle-aged men walking arm-in-arm with their Sofia Loren-lookalike dates and whistling Rossini, sexual impulses appropriately in tact. I imagined that the people of Piazza Verdi would be dapper and inspiring and that I would enjoy walking among them after late-afternoon lectures at the University to my quaint bohemian household on the Via Petroni and to Brando, who loved me. At any rate I did not expect that by mid-February, once the semester was in full swing, the Piazza Verdi would be fixed in my mind as a living illustration of Dante’s hell; nor did I expect that this lot beside the opera house would acquire with the onset of springtime heat an impenetrable stench akin to that of taped-off, waste-ridden sections of zoological parks to which visitors are forbidden access.

I learned not long after moving in that neither the neighborhood nor the apartment would meet the standards I had set for them. Brando, for example, in spite of his charms, was little compensation for his owner and the padrone of Apartment Twenty-Two. Pippo was freakishly tall, approaching seven feet, with crooked front teeth, a face covered in coarse brown hair and a habit of changing his clothes about every fourteen days. He was the victim of a broken leg sustained during some mysterious bout of drunken debauchery in Ferrara not long after my arrival. At first I had thought the seven feet of him charming, the shoulder-length, matted hair and outspoken anarchism all signs of an admirably free spirit. There really was something of the lover in his manner of eating soup like a prehistoric ogre. He called it Zuppa di Bastardo, “fatta da bastardi e mangiata da bastardi,[2] a piccante slop of beans and potatoes he had invented in the mountains of Trentino years before moving to Bologna for classes at the art school he never attended.

The assistant chef was Duccio, Pippo’s long-time friend who had moved with him from Trentino to “study” in Bologna – not officially a roommate but an honorary bearer of the key he refused to renounce on moving out of Via Petroni the previous year to chase after some Ilaria in Florence. Whenever he needed a respite from amorous pursuits he returned to our place, often sleeping on our couch and (to his credit) paying a small share of the grocery bill. Duccio had beautiful, crystalline, cracked-out blue eyes.He was a bit thinner than Pippo and, though shorter, had more trouble carrying around his body, so that he was always hunched-over in a sinister-looking posture. Otherwise the two looked very much alike and were difficult to tell apart for the first couple of weeks. I liked to watch Pippo and Duccio stooping over their cracked earthenware bowls and licking them clean and collecting our bowls to lick after we had finished eating or appeared to have finished eating. I liked when the kitchen smelled more like Pippo and Duccio’s rosemary legume slop and less like cannabis. In fact there were aspects of Pippo that I liked very much, but his injury was a cross for us all to bear.

For months he lived on the couch in the kitchen by day and barked at us more loudly than Brando did. Gwladys Guez, the little French coquette from Brittany who shared my room, took to seducing her acquaintances just to get out of the house. Her most tenacious suitor was a man in his sixties who claimed to manage the jazz band we heard every weekend in the underground crypt and who stopped by occasionally to stock our pantry with champagne and coffee cake. Samir, a computer programmer and the flatmate whom Pippo called “Maghreb,” bought a Vespa and took a job delivering pizzas for peace of mind. Anna stopped frequenting her painting classes to take care of her wounded lover. In the mornings she drew up a stool next to Pippo’s sofa and didn’t budge for interminable shifts, taking breaks only to cook Pippo’s meals and brew him coffee. Together they played an American computer game on Samir’s old laptop, and Pippo thundered when the screen cut off every couple of minutes. After a month or so, he became maniacal and spoke to no one until he could conquer “Monkey Island,” with the s pronounced like a z, in the duration between system crashes. Anna continued to brew his coffee. I washed his dishes. Oli l’Olandese,[3] another former roommate in possession of a key, cleaned the apartment every week when she could carve out a break from writing her thesis. She studied anthropology and may very well have hung around the apartment out of an intellectual interest in our living habits. Oli and I took turns walking Brando in the early afternoons and – after he started sneaking in the kitchen every night to defecate on the small patch of floor space where Pippo was known to rest his beer can – in the evenings, too.

All this might have been fine, a tolerable discomfort, until the suspicion occurred to Gwladys Guez and me that Pippo may not have been so incapacitated after all, on the evidence of his nightly, sleep-depriving, earth-shattering sessions of faccendo l’amore[4] with Anna, more than two feet shorter than he and apparently not very difficult to please. Sometimes he played a recording of Jimi Hindrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” to obscure the noise, but an electric guitar was no match for their moaning and acrobatics. These incidences began in March, when the winter chill was dissipating and it became possible to sleep without several layers of clothing, the sheets of cellophane we had duck-taped to the walls in replacement of several broken windows being sufficient to shut out the mild frosts. Around the time the poplar trees began to bloom, Pippo and Anna started having the kind of sex that the poets associate with springtime. It was the kind of sex that made one on the outside feel destined to be alone for the rest of her life, and resentful of doing everybody’s dishes.

In fact it wasn’t terribly long before I gave up on the dishes, one afternoon when Pippo was dictating the recipe for stuffed peppers to Anna and lifting up the waist of Oli’s skirt to examine her backside as she knelt on the floor wiping up spilt red wine.

“You are getting tan,” he told her.

He had beaten Monkey Izland that morning and was feeling satisfied with himself, like some 19th-century mustached game-hunter who had set out in a colonized jungle and caught himself a real monkey.

Oli looked up at Pippo and at Duccio sitting next to him. Then she bent over again and continued scrubbing.

Duccio had explained to me a few nights before that things were strange between Oli and him since he had taken up sleeping with her and with the Florentine Ilaria at the same time. His Italian grammar was such that it remains ambiguous as to whether Duccio meant he was carrying on simultaneous, separate affairs with these women or habitually sleeping with them both at once, with three to a bed, in a jealousy-ridden ménage-a-trois. Regardless, he seemed rather proud of himself. Torn between his best friend and his faithful housekeeper, Pippo had not yet taken sides with either Duccio or Oli and had been deliberating for weeks.

“Oli is profoundly envious,” Duccio had confided me that evening as he helped me find a concert hall I should have looked for on my own. “She is in love, and a woman becomes irrational in such a condition. But she can be a very sympathetic person.”

All this I could read in Oli’s glance to the two men, to the 26-year-old jobless men who reeked of cigarettes and limoncello and made excellent soup and rarely bathed and had worn holes in the upholstery of our sofa. I dropped the encrusted plate I was working on into the sink and said to Pippo in my broken Italian, “It is not done that way. Do not do that. It is maleducato[5] and shows that you don’t respect anyone,” whereupon Pippo became enraged at me for the first and only time during my tenure at the Via Petroni, slammed down the screen of Samir’s laptop to better see my face and said, “Basta con questo moralismo sessuale.[6] Oli is my friend and she will tell me if she doesn’t like me looking at her culo. Until then I look at her culo[7] whenever I want. Mind your own business. Cazzi tuoi.[8]”

I stood silently for a moment and put down my dish with as little clatter as possible and went to my bedroom to start planning a trip to London for the next weekend. And I made a policy of letting the dishes pile up indefinitely.

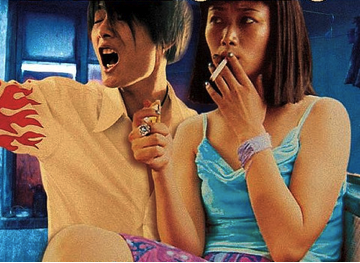

But those versed in the politics of Bologna’s social scene would notice readily that my flatmates were not of the typical Via Petroni crowd we had been warned of, the punkabestia, dreadlocked self-proclaimed “beast-punks” in their twenties, dressed in gothic attire and fond of sitting under the porticos, or out in the open on Piazza Verdi, with their small-eyed, swollen-nippled or grossly-testicled, vicious-looking pitbulls and drinking themselves into a rambling stupor. They were generally harmless, aside from the occasional sexist remarks the more intoxicated male punkabestia would hurl at fair-complexioned, foreign-looking girls, and after a month in Italy we were deaf to such comments, anyways. Various creation myths circulated that explained the punkabestia’s origins. Some say there had been a law in Italy, inspired the culture of Catholic benevolence, that the sole owner of a domestic animal could not legally be sent to jail for any reason, and drug-dealers took to buying dogs as insurance against imprisonment. Others believe that at one time pet-owners were given small stipends by the government, making dogs a popular accessory among unemployed students. Whatever the reason, most locals agreed that about ten years before my arrival in Italy it became all the rage among Bologna’s youth to dress “alternatively” and roam the streets with snarling dogs on metal leashes. (“Bologna has a vibrant student community of cosmopolitan intellectuals,” I once wrote home to my father in South Carolina, paraphrasing a study abroad brochure I had read somewhere along the way.)

My roommates and I found prideful solidarity in our decidedly not being among the punkabestia ranks, and in our not taking them seriously. But their presence around the Via Petroni was enough, for a spell, to make me dread my evening walks home through the piazza that, like so much else in my life, I had romanticized prematurely based on its name, on the engraved marble sign at its entrance, on its title in the index of my map.

But not long ago, at the height of my disillusionment with the place (the kind I’m told everybody goes through for a couple of weeks upon moving overseas), just after I had stepped through a bevy of drunken twenty-somethings, sitting indian-style among broken bottles and puddles of urine and stinking up the Piazza Verdi with the dogs they had bred and cultivated to look as dumb and wretched as themselves, trashing the medieval architecture they felt it their political duty, as anarchists, to disrespect – it was just after I had picked my way through a crowd of these that I climbed up the slippery marble stairs of my apartment building and saw scotch-taped to the wall next to a neighbor’s door the following message in blue ink on an eight-and-a-half-by-eleven-inch sheet of white paper:

Ho trovato una maglia nella Via Petroni 7. È VERDE [in green marker] con maniche NERE [in black marker]. Era sporchissima ma l’ho lavata. È molto bella e fa ancora fresco fuori e voglio consegnarla alla person giusta. Se è tua, chiamami!!”[9]

There were a careful sketch of the sweatshirt and two exclamation marks after the text and the girl’s telephone number written large and boldly across the bottom of the sign. I thought for a moment of this neighbor of ours, a friend of the apartment who often showed up asking for cigarette rolling papers or sugar and was one of the few who could be counted on, my flatmates assured me, to return the favor. I thought of her, dreadlocked and foul-smelling, washing the lost sweatshirt, rummaging through her apartment for a blue pen and green and black markers and clean white computer paper and scotch tape and drawing up a plan for this magnificently thoughtful sign of hers. I stood there in the hallway caught up for a few irrational moments by a visceral love for Italy, for Italians, for the neighborhood, for the Via Petroni, punkabestia and all. I loved Pippo’s broken leg and Anna and Gwladys Guez and Samir and Oli and even Duccio and Brando’s diarrhea and the ubiquitous stench of alcohol. I loved the past few months and the next few months to come and I rushed into my apartment and forgot about the James Joyce novel in my purse.

Pippo and I were the only flatmates around that night; we spent the evening on the sofa eating tough-crusted Pugliese bread and olive oil with Brando. Pippo honored my request for his famous impression of the effeminate Frenchman who, years before, had refused him admission to a campsite because he had not pronounced bungalow to the Frenchman’s liking. He thanked me when I got up to fetch him a cigarette lighter. He told me affectionately that he was sure I had not voted for Regan. I ate my bread and drank our good wine and listened politely and contentedly to Pippo’s theories on sexual liberation and even agreed with a sentence or two.

——————————————————————————–

[1] 7 Petroni Street

[2] “made by bastards, eaten by bastards”

[3] Olandese: Dutch. Oli’s father was from the Netherlands.

[4] lovemaking

[5] rude, the result of poor upbringing

[6] “Enough with this sexual moralism.”

[7] ass

[8] Vulgar colloquialism for “Mind your own business.” Literally, “your dicks.”

[9] “I have found a sweatshirt in the Via Petroni 7. It’s GREEN with BLACK sleeves. It was extremely dirty but I washed it. It is very pretty and it’s still chilly outside and I want to give it back to the right person. If it’s yours, call me!!”