By: Laura Charney, RightsViews Staff Writer

This April, the Center for Palestine Studies at Columbia University hosted the “Gaza on Screen” film festival highlighting films made by Gazans and about Gaza. Curated by Dr. Nadia Yaqub, “Gaza on Screen” offered an invitation to not only bear witness to the lived struggles and resilience of Gazans, but also the opportunity to engage the ways that Gazans articulate and envision their own experiences.

For over twenty years, Palestinian film festivals across North America and Europe have brought Palestinian stories to international audiences. However, Palestinians in Gaza face particularly prohibitive measures that inhibit the communication of their stories. Since 2007, Israel has maintained a blockade on Gaza, controlling its airspace, coastline, and borders, and restricting the movement of goods and humans entering or leaving the territory.

It was not until this past April at Columbia University that a film festival focusing exclusively on Gazan stories came to life. In an attempt to shine light on the issues specifically facing Gazans, “Gaza on Screen” strove to unsettle some of the borders that hinder the circulation of Gazan stories.

The three-day-long film festival programmed feature-length films, documentaries, short films, and a master class with Abdelsalam Shehada, a Gaza-based film director who has made over 20 documentaries.

There was also a Q&A with some of the student filmmakers who directed the short films. Mohammed S. Ewais, a student at Al-Aqsa University, joined the film festival over Skype from Gaza City to discuss his film, We Love Life (2015), a documentary-style portrait of Gaza-b ased graffiti artist Belal Khaled, who transforms architecture gone derelict from Israeli explosions into works of art. The title of the film comes from the Mahmoud Darwish poem: “We love life if we find a way to it.” When asked if there was a political message in his film, Ewais responded, “To spread awareness of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. No one knows what is going on here.”

ased graffiti artist Belal Khaled, who transforms architecture gone derelict from Israeli explosions into works of art. The title of the film comes from the Mahmoud Darwish poem: “We love life if we find a way to it.” When asked if there was a political message in his film, Ewais responded, “To spread awareness of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. No one knows what is going on here.”

Because of the embargo, Gaza faces a water crisis, constant electricity outages, destroyed infrastructure, and a deteriorated economy. Israel’s multi-layered apparatus of state control is justified under the pretense of security, while denying Gazans the tools to secure their own livelihoods. The intensive border regime means that international perceptions of Gaza are often marred by the impossibility of accessing and understanding the actual experiences of Palestinians in Gaza.

In the keynote speech at the Dreams of a Nation Palestine Film Festival at Columbia University in 2003, Edward Said said that “the whole history of the Palestinian struggle has to do with the desire to be visible.” Palestinian-produced films, like those shown at “Gaza on Screen,” engages this struggle, through bringing to the fore the names, memories, and personalities of individuals and families who are often represented in broad and stereotypical strokes in dominant media narratives.

The pursuit of being “visible” is also bound within the limitations that Palestinians face when attempting to access their own written histories. Since Israel invaded Beirut in 1982, Palestinian national archives have been in the hands of the Israeli Defense Force. The Israeli state has placed restrictions and legal obstacles that hinder access to the Palestinian archives, effectively controlling the possibilities of generating Palestinian-produced historical knowledge by rendering it inaccessible to its traditional owners.

Visual material is one force that disrupts this censorship. Film affords the potential of narrating stories that have be en displaced in the archives. Palestinian cinema – factual and fictive – has been a crucial force in making visible political realities that authentically reflect lived experiences.

en displaced in the archives. Palestinian cinema – factual and fictive – has been a crucial force in making visible political realities that authentically reflect lived experiences.

The circulation of Palestinian film allows stories to speak to audiences across borders. When describing his feelings on visual narratives, Ewais stated: “Cinema is my only way out.” Because of the blockade, he has never left Gaza. Ewais is one of the many directors and filmmakers who contributed to telling Gazan stories at “Gaza on Screen.”

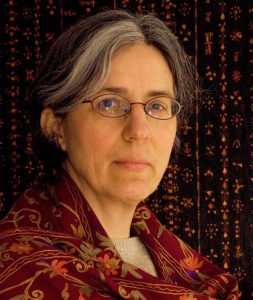

“Gaza On Screen” was curated by Nadia Yaqub, Professor and Chair in the Department of Asian Studies and Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at UNC Chapel Hill. Dr. Yaqub’s research critically examines Arab cultural texts, and has recently focused on Palestinian literature and visual culture. Her latest book, Palestinian Cinema in the Days of Revolution (2018), analyzes films of the Palestinian national liberation movement through the late 1960s and 1970s.

I spoke to Dr. Yaqub over the phone to discuss Gazan self-representation on film, the possibilities of visually and transnationally communicating resistance, and the urgency of telling stories that are meant to be silenced.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Laura Charney: What did you want to illuminate about Gaza when curating this film festival?

Nadia Yaqub: The idea was Hamid Dabashi’s [Hagop Kervokian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University]. He approached me and asked me to curate this film festival. I had never done any work specifically on Gaza, but it immediately sounded interesting. I have done many years of work on Palestinian cinema, and I had thought a lot about the difference between filmmaking in exile, filmmaking under occupation, and the filmmaking among citizens of Israel.

Gaza as a particular unit has an interesting, distinct history within the larger Palestinian history because of its relationship to resistance. The resistance movement, the PLO as a militant organization, the first Intifada, all have their origins in the Gaza Strip.

Geographically, it’s this little piece carved out of Israel. Gazan residents live in close proximity to the homes that they lost in 1948. The huge influx of refugees in 1948 utterly changed the demographics of the area, and that has just been exacerbated ever since, through rapid population growth. If you can define the Palestinian condition as one of exile and displacement and ongoing dispossession, Gaza is always the extreme case.

There is a lot I couldn’t include in the film festival, but I was immediately interested in the variety of film material – the ways in which Gaza had been manipulated by different actors in film, the ways in which Gazans had represented themselves, the ways in which Gazans or others have tried to intervene in the visual materials about Gaza such that it is not only defined by conflict and dispossession, but also in fiction film, experimental film, in documentaries.

What I tried to do with the festival was very briefly trace a history of image making. At the same time, include these various types of representations and to represent different perspectives, but always varieties of what I would call a Palestinian-centric perspective. I wasn’t interested in including how Israel views Gaza, or how Iran or Hezbollah, who are close allies of Gaza, support or use Gaza for their own ends. Those are all interesting questions that I did not want to broach. There is a lot of film that is made from the perspective of solidarity activists – people who were on the ground in 2008, 2009, who participated in various flotillas, for instance. I wasn’t interested in those stories for the purposes of this film festival. That’s what I mean by a Palestinian-centric view.

LC: Because Gaza is under blockade, this film festival provided an opportunity for many to be let in on how Gazans view themselves, and Gaza itself. International understanding of Gaza often comes from how journalists cover it, or how the Israeli media portrays it. The student films provided a kind of radical disruption from these dominant representations – hearing their stories, the way they want to tell them, is quite rare.

NY: Yes. Film is obviously a form of communication. People make films in order for other people to see them: there’s something sort of inherently transnational about it. In some ways that are different from literature, film is about communicating outward. Films about Palestine are almost always made for outside audiences. Within that framework that’s kind of messy and transnational, it’s hard to define – what is a Palestinian film? Does the director have to be Palestinian, and what does that mean? Do they have to have Palestinian blood in their veins? Do they have to have lived in Palestine or within a Palestinian community? Those are messy questions. Nonetheless, we somehow, through that messiness, have to sift out the Palestinian voices, and the Gazan voices, and attempt to recognize what they are saying. Some films in the series – Antoni Akacha’s film Voices from Gaza, and Savona’s film Samouni Road – were not made by Palestinians, but I did feel as if they fit within this framework. That is probably a product of those filmmakers’ long engagement with Palestine and Gaza.

LC: I noticed that a lot of the films on the lineup were documentaries, ethnographic, or experimental of some kind. I’m thinking about what metaphor can do to express the inexpressible, and the choice behind not including so many fictional films. Is there a draw in Gaza toward experimental or documentary films? How does this reflect the landscape of filmmaking in Gaza, and how Palestinian and Gazan filmmakers articulate their own stories?

NY: In my research, I found that there are about 15 feature-length fictional films that have been made about or in Gaza. Five of them were made in Egypt in the fifties and early sixties – they’re Egyptian films, where Gaza is this territory where Egyptian characters go to work our their problems. They’re very melodramatic.

11 feature films have been made from the early 90s until today. That’s not insignificant if you think about how tiny Gaza is. But the vast majority of films are documentary. The number of essay and experimental films in the program are not reflective of their percentage of output.

A lot of documentaries made about Gaza are international – to tell an international audience, ‘this is how difficult it is to cross borders,’ ‘this is what’s going on with fisherman,’ ‘this is what it’s like to live in a refugee camp.’ Where you draw the line between a reportage, which is a bit longer than a news story, and address in a little more depth a current situation, and a documentary, is almost impossible to decide sometimes. There’s a huge amount of this material, but it makes it a conversation about journalism, rather than about filmmaking. There is a bias toward the unusual in the film festival that I did.

LC: Considering the history of stolen Palestinian archives, or archives that are inaccessible to the public, I would imagine that you faced some limitations in putting this selection of films together. What were some of the challenges you faced in curating this selection?

NY: For this film festival, the issue wasn’t really stolen archives. Of course, there is the famous case of the five PLO archives that disappeared during the Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982, including the archive of the Palestinian Cinema Institute, but bear in mind that that filmmaking did not include very much material about Gaza. I did include one of those films which has been found – it has not yet been restored so the copy that was screened was scratchy – but that may be the only film from the early period, before 1982, that the PLO made that focused on Gaza.

The problem of the archive more generally was definitely a challenge. This is a particularly Palestinian problem in the sense that there is no national Palestinian archive or archive project. To be fair, if you look across the Arab world, the difficulty of accessing archives of Arab film in other Arab countries has not necessarily helped film scholarship on the Arab world. There’s the notorious case of Syria. From the mid-60s until the Syrian civil war, they funded, produced, many hugely interesting films. Those films would be released, often during the Damascus International Film Festival, perhaps some of them would screen at, say, the Carthage Film Festival in Tunis, and then they were locked up and no one got to see them. Film scholarship on Syrian film has been severely limited for that reason. This may be one of the most extreme cases, but it is also not easy to do research on Algerian film, Tunisian film, Moroccan film.

I could imagine if the PA [Palestinian Authority] were to form a film archive, the problem of Palestinian politics – the Fatah/Hamas split, for instance – would be the big issue, and how the PA has dealt with the PLO’s militant past. Those questions would probably give rise to a problematic archive.

LC: Something that came up among audience members throughout the film festival was how resistance and political struggle is framed in these films. Abdelsalam Shehada’s films, for instance, are gorgeous, but they also represent an ideal of nonviolent resistance. This is something that some people grappled with. At the same time, I think the goal of a lot of these films was to disrupt normative assumptions about Gaza. How do these films situate themselves within a wider history of Palestinian political struggle in cinema?

NY: I would say that filmmakers are quite savvy in responding to the global context in which they are working. In the 1970s, when you had a militant Palestinian film movement, the idea of national liberation through armed struggle was global. It was accepted as a legitimate means for oppressed people to achieve their rights. There was, for instance, the Vietnam War, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, the struggles in Latin America – they are allies of the PLO. The PLO were not, by themselves, advocating armed resistance.

The struggle was placed within the context of the Cold War, so it’s complex. Of course, many of these organizations were labelled as terrorist within mainstream media in the West, but there were also allies. It was a completely differently landscape. Now, the ideological battle line is drawn between the Muslim world and the rest. So, Palestinian militancy is really only alive within an Islamic militant movement. There’s only very little marginal support for that in the West, and there’s lots of reasons for that – I’m not arguing by any means that leftists in the West should support Hamas or Hezbollah, but we also don’t need to glorify or romanticize the nature of armed resistance from the 1970s. That was really problematic and compromised, both in terms of the Palestinian movement, and globally.

For a Palestinian filmmaker who wants to engage with a western audience, there is no space for any kind of claim of violent resistance. Nonviolence is the only space. You have to work within the space you’re given.

LC: This is a really crucial distinction – understanding who the films are made for. Not to sound insensitive, but there is a need to humanize Gaza, because of the dominant narrative that associates Gazans with terrorism. That was, to me, why a film like Samouni Road was so powerful.

NY: I think that’s an extremely powerful film. There was a scene that really stood out to me, where the family talks about their apolitical stance. They’re not a part of any political party, they don’t want money from Hamas, they don’t want their tragedy to be exploited. It seemed to me – that was a message to us.

LC: Yes – it also makes me wonder, as a western audience, the complexity with which we are prepared to give Palestinian subjects on film. The dichotomy between peaceful resistance – being apolitical, nonviolent – versus active political resistance, is reductive. Yet it is only the former that tends to be palatable to western audiences.

NY: This is interesting in the context of the history of human rights filmmaking. Monica Maurer is a German filmmaker who worked within the PLO in the last years of Beirut. 1979 was declared the UN International Year of the Child, so a lot of filmmakers took advantage of that to create films about children. [Maurer] made a film called “Children of Palestine.” The film is structured around the declaration of the rights of the child – they have the right to family and freedom, to work and education and time to play, a national identity, and several other rights. She structured the film around each of these rights and shows how the PLO, through its armed struggle, is working to mitigate the ways in which Israel is denying children these rights. The film won first prize at the International Human Rights Film Festival in Bulgaria in 1980. So militancy, as a way of working towards human rights, used to not be incompatible. Returning to what we were discussing earlier, the discourse has changed around the world. There are things you could say in the early 80s that you cannot say now.

LC: It is fascinating to think of the construction of victimhood on film – how constructing the ideal victim often necessitates taking away any kind of political agency.

NY: Yes, and that is the central challenge that Palestinian filmmakers face today. I suppose that this was one of the things I was working through in curating the film festival: exactly how you can communicate Palestinian experiences in a way that works in this context, without reinforcing that image of the Palestinian as a victim.