An increase of migration in recent years has spurred a global conversation that asks: what is the responsibility of countries, particularly democracies, toward migrants? Relevant discussions have had real consequences on-the-ground for both migrants and states, leading to legislation which has had positive effects, and also to massive human rights violations. I examine the broad movements in worldwide migration in the past few years and pull out important themes which can be gleaned from global happenings.

The State of International Migration

According to the UN’s International Migration Report released on December 18, 2017, there has been an increase in people moving away from their country of birth by 49% since the start of the 21st century. Yet according to the 2018 World Migration Report published by the IOM, this increase in migration remains comparable to the world population; the scale of growth remains stable in regard to population.

A greater number of international migrants are moving into OECD countries to live permanently, part of a trend tracked by UN DESA. In contrast, 2017 saw refugees and asylum seekers predominately living in low- to middle-income countries, with only 16% residing in high-income countries. Thus, although high-income countries did host a majority (64%) of international migrants in 2017, with the United States hosting the largest number per country at 19% of the total, high-income countries are on average accepting the fewest number of refugees and asylees.

Despite this low acceptance rate, the need for host countries to accept refugees and asylees has increased, with the highest number of refugees recorded 22.5 million refugees and another 2.8 million awaiting adjudication of their asylum claims at the end of 2016. Since then, this number has increased to 25.4 million in 2018 because of the conflicts in Syria and Venezuela.

Migration in State Politics

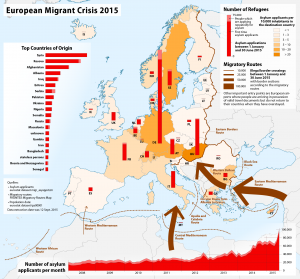

According to a Yale study, in recent years nationalism, populism, and/or identity politics have led to a rise in conservative policies across Europe and in the United States, especially in the areas of immigration, affirmative action, police and criminal justice. A BBC report further showed that political parties associated with nationalism and the far-right have gathered greater support mainly due to tension around national identity and globalization. The five countries highlighted by the report with the most votes for a nationalist party include Switzerland (29%), Austria (26%), Denmark (21%), Hungary (19%), and Finland (18%). In one poignant example of how powerful these sentiments are, anti-immigration was cited as the most fundamental motivation behind Brexit by 88% of people in the UK. In Denmark’s case, in August 2018 the country instituted a ban on face coverings, intended to prevent Muslim women from wearing the niqab or burqa. Other European countries with this ban include Belgium, Austria, France, the Netherlands, and Bulgaria. Other countries which instituted anti-immigrant legislation within the last few years include the U.S. with its 2017 move to drop the ceiling for admitting refugees from 110,000 to 50,000 (and then further reducing admissions to 45,000 for 2018); in June 2018, Hungary instituted a “Stop Soros” law intending to criminalize anyone offering aid to migrants without legal status. Then, in September of 2018, Italy increased the ease at which it could deport migrants and suspend asylum applications for individuals deemed “socially dangerous” or with any criminal history. As evident in these cases, anti-immigrant sentiment no longer exists solely in conversation and political rhetoric, but now has a strong presence in policy with real implications for migrant and refugee communities.

At the heart of anti-immigrant sentiment is a basic fear of outsiders, which is propagated by misinformation. According to a study sponsored by the National Bureau of Economic Research, native-born citizens across the world believe that 1) there are far more immigrants in their country than in reality, 2) immigrants are more culturally and religiously different than native-born citizens, and 3) immigrants have less education, are less likely to become employed, less financially stable, and rely in greater numbers on government aid, than native-born citizens. In addition, immigrants and especially those from lower-income countries have been politically problematized and put forth as a “new” issue which requires expansive and lightning-quick responses by power-grabbing governments. Yet in the example of the United States, this is proven to be false: the U.S. hosts almost three times the number of immigrants than it did in 1970, yet it still has fewer than the 9.2 million immigrants who lived in the U.S. in 1890. The problem is evidently more one of perception. For example, in the European countries that have instituted bans on face veils, only a minute percentage of women in these countries actually wear such attire. The bans, then, are a symptom of Islamophobia and a fear of losing grasp of vaguely-defined European identity. In the previously mentioned Yale study, the authors, Craig, Rucker, and Richeson advise their readers that the core issue behind increasing conservative policies in the U.S. is an identity threat felt by “White (Christian) Americans” who are afraid of losing the status and privilege lent to them in American society by these identity factors. Fundamentally, there is a looming fear that some essential part of national identity is at risk. This fear has led countries to rush to to protect borders, as made evident in President Trump’s obsession with building a wall.

The International Responsibility of States

Much of the anti-immigration legislation is in violation of international refugee policies, which, according to the 1951 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, mandate that states must process asylum applications of persons who enter the border. States have a responsibility to protect persons with “well-founded fear” of persecution on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, and/or membership in a particular group. States cannot, according to Article 31 of this convention, impose negative consequences against individuals who enter the country illegally but then apply for asylum, although states are allowed to limit the amount of time in which individuals may apply.

Furthermore, some anti-immigrant state policies are directly responsible for migrant deaths. In an important and devastating example, in August 2018, Malta detained three NGO rescue ships to prevent them from operating along the migration route from northern Africa and southern Europe. These rescue missions were begun as a civil society response to the extremely high death tolls along this migration route (recorded at 5,143 in 2016 by the IOM). According to the IOM report, these deaths mainly occur due to environmental conditions along the route, physical violence, risky transportation methods, and lack of safe food and water along the route. In addition to the detention of ships, Italy and Malta have both closed their ports to other NGO rescue vessels operating in the Mediterranean. By halting NGO activities, Italy and Malta have significantly increased the danger faced by migrants as they seek asylum in Europe.

Now What?

Currently, the majority of anti-immigrant, anti-refugee politics have been limited to just that – political rhetoric – yet the countries which have instituted real, problematic legislation are cause for a sobering response. The recent Global Compacts, one for migration and the other on refugees are one major step toward a unified international response to increasing migration and a greater number of refugees. The Compacts represent a productive response to the initial question I presented about the responsibility of states to migrants; this question, though, disregards the fact that migration is not a one-way process even for Global Northern countries. Perhaps a better question would be, what is the relationship between democracy and migration? In the spirit of the Global Compacts, we should be looking at this issue with the understanding that international migration is increasing. Instead of a burden, this is an opportunity to work as an international community to reinvent a world in which mobility and globalization are inevitable and embraced for their potential.

By SaraJane Renfroe. SaraJane is an MA student in the Human Rights Studies program, focusing on migration and refugee integration.