By

Karen Ross

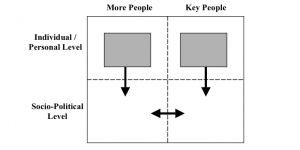

I was inspired, years ago, when I first encountered the Reflecting on Peace Practices (RPP) project at CDA Collaborative Learning Projects , and was particularly struck by a diagram I encountered in one of the project’s publications: Confronting War: Critical Lessons for Peace Practitioners. The diagram (below) encapsulates what, for me, is the essence of assessing the ‘impact’ of peace building interventions: a need to link changes among individual participants to larger groups and to change at the socio-political level.

I found this diagram (and the publication as a whole) inspirational because it resonated with questions I had been trying to answer for a while: what difference do grassroots programs bringing together youth in conflict contexts make? How do we know whether these programs have an impact – on individual participants, on other individuals, and on conflict-affected contexts as a whole?

In my years as a scholar and practitioner of dialogue and peace education, I have read a lot of research attempting to answer these questions. This scholarship has taught me a lot, but I also am frustrated by the focus most of it places on examining impact in a relatively narrow manner: as cognitive or attitudinal change measured over a few months. This is not to say that such research is not valuable – in fact, most studies are methodologically rigorous and provide useful information about the potential of peace education programs to change (or not) the perceptions of individuals who participate in them. In other words, this research is important in helping us understand the short-term cognitive, attitudinal, and even to some degree behavior change facilitated by participation in peace education endeavors. Still, what is missing is an understanding of how these changes fit into the bigger picture – that is, whether and how organizations implementing peace education achieve their goals of contributing to a more just and peaceful society.

This is where the diagram from Confronting War comes in. Indeed, much of the field of conflict resolution, the Reflecting on Peace Practice project included, has taken a broader turn in defining and assessing impact that I think can also benefit research focused more specifically on peace education. For instance, conflict resolution scholars have suggested indicators of broader change such as: increased demands for peace by groups of individuals; adoption of ideas from conflict resolution interventions into official negotiations; and continued, specific actions by participants in conflict resolution programs that focus on responding to the needs and concerns of the other side.

Of course, we can’t expect programs targeting school-aged children to show a direct link to changes in government negotiating positions. On the other hand, we can examine and learn from the long-term activities of peace education participants. A recent project of mine, for instance, focused on involvement of Jewish and Palestinian citizens in activities promoting Jewish-Palestinian partnership, as assessed years and decades after their participation in one of two Israeli peace education programs. I found that approximately half of these individuals (65% from one of the two programs, and about 40% from the other) are actively involved with other dialogue initiatives, peace-building organizations, or activities that focus on changing Israeli society to be more equitable for all of its citizens. Even after all these years, many pointed to certain aspects of their participation in the peace education programs as inspiring their later actions. Some spoke about acquiring political knowledge that inspired them to think critically about Israeli society and work to change it. Others mentioned being inspired by seeing equality between Jews and Palestinians modeled among program staff – seeing this gave them hope that such equality might someday be possible in Israeli society, and motivated them to work towards that reality. One woman told me that her peace education participation “changed my life,” and is the primary reason why she has the career she does today.

It is clear that for many alumni of at least these two peace education programs, participating in joint Jewish-Palestinian endeavors as youths played a major role in their decisions to undertake additional activities that emphasize the pursuit of peace and justice. And while it’s not possible to generalize to all peace education programs, this finding is important because it suggests that peace education initiatives can not only set the stage for long-term change among their participants, but that the nature of that change builds into other peace-building efforts in societies suffering from conflict – suggesting that these programs have a broader impact than what scholarship to date has noted.

There is much more that can be said about this. For now, let me end by reiterating that I believe we need to think much more broadly about what constitutes impact and how it might be assessed. Only by doing so can we know the true value of peace education endeavors.

Karen Ross recently completed her PhD in Inquiry Methodology and International & Comparative Education at Indiana University, where she continues to teach as a research methodology instructor.

[KR1]Link: www.cdainc.com