Die Another Day

About 36 lives in the United States might be saved in the upcoming year because of a critical drug shortage. Saved. That is because the drug at issue is an anesthetic used by many states in the US for lethal injections. This scarcity is forcing states to reexamine and restructure their death penalty procedures. Most have elected to move forward and continue executions with untested, unregulated drugs, prompting a wave of legal challenges concerning the Eighth Amendment rights of death row inmates.

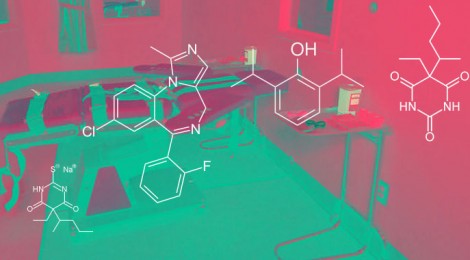

The shortage of the anesthetic, sodium thiopental, began when the manufacturer of the drug, Hospira Inc., an American company, moved its production to a facility in Italy. Italy refused to export the drug for use in lethal injections, in compliance with a European Union statute banning the export of any product to be used in capital punishment. Following Italy’s lead, other drug manufacturers have also halted the sale and distribution of potentially lethal drugs to prisons and corrections departments to separate their product from any association with capital punishment.

In 2008, with a split decision in Baze v. Rees, the Supreme Court found lethal injection to be a constitutionally protected method for capital punishment, not in violation of a citizen’s right to be spared from cruel and unusual punishment. In their arguments, the petitioners advocated for the use of an alternative one-drug protocol. In his majority opinion Chief Justice Roberts claimed, “The alternative that petitioners belatedly propose has problems of its own, and has never been tried by a single State.”

Now the 34 states that relied on sodium thiopental find themselves seeking such problematic alternatives. Florida used midazolam, commonly used as a sedative, in a 2013 execution. After learning of the drug’s use, Hospira added it, as well as three other drugs, to the list of pharmaceuticals it will no longer distribute to prisons. In the same month, Missouri planned to use propofol, an anesthetic, in lethal injection, but governor Jay Nixon delayed the execution as the drug’s German manufacturer Fresenius Kabi threatened to limit distribution. A shortage could have impacted millions of lives, as it is estimated that the drug is administered 50 million times a year in the US.

With the most common drugs becoming more and more scarce, states find themselves unable to perform executions via their standard or backup protocols. The legal process for adjusting methods of capital punishment varies from state to state. Some require the submission of formal proposals, available to public comment and challenges in court, while others can be altered by executive authority.

The most viable solution appears to lie with compounding pharmacies, companies that manufacture drugs for patients with uncommon medical needs. Although located in the US, the pharmaceuticals produced by these manufacturers are not subject to regulation by the FDA. Additionally, states, hoping to avoid more shortages, are withholding the names of the sources of their drugs so that these companies will not be pressured into limiting distribution.

This year Georgia, Texas, Ohio, and Missouri have all obtained drugs from compounding pharmacies this year. These states plan to use a sedative, pentobarbital, substituting the usual three-drug cocktail with one large dose. As this procedure was put in place, Georgia passed a law to keep the identities of the sources of its drug confidential. Inmate Warren Hill challenged the constitutionality of this law, and in state superior court a judge found the law to be in violation of the Eighth Amendment. This ruling sets a precedent for challenges of similar confidentiality laws in Arkansas, Florida, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Tennessee.

In addition to the secrecy provisions, the method of execution itself is the subject of many legal challenges. In a 2012 case, Hooper v. Jones, an Oklahoma inmate challenged the use of pentobarbital. A US Court of Appeals upheld the constitutionality of the procedure. Although Hooper’s execution was not halted, federal courts continue to hear similar cases regarding pentobarbital. Ronald Phillips, on death row in Ohio, is to be put to death with midazolam, the same drug used by Florida. He has challenged not only the safety and effectiveness of the new procedure, but also the state’s administration over execution responsibilities.

Some states, recognizing the continuing trend of shortages and the numerous legal challenges brought on by these new methods of lethal injection have heard more radical suggestions regarding the future of capital punishment in the US. Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster (D) and state senator Kurt Schaefer (R) advocated for a return to the gas chamber. The senator wrote an appeal for construction of a new chamber, as this method has not been used in the state since the 1960s.

As methods of capital punishment become less accessible to the states, the validity of the punishment comes into question. 14 states are unaffected by these shortages, as they have banned capital punishment. Might the best solution for the others be to join them?